Pierre Bonnard painting in the studio at his home in Le Cannet, south of France, 1946, photographed by Gisèle Freund

Photo © IMEC, Fonds MCC, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Gisèle Freund

Dina Vierny, best remembered as the muse who inspired the elderly Aristide Maillol to revivify his art, also modelled for Henri Matisse, Raoul Dufy and Pierre Bonnard. In a 2005 interview, she recalled accompanying the latter to a Salon d'Automne exhibition in Paris that included his work. ‘We were looking at these paintings, which belonged to private collectors or museums, when suddenly I saw him take out a small can of oil and his brushes in the middle of this huge hall – and he started to touch them up. No one saw us. He explained that a painting was never finished. As he was correcting it, he said: “It lacks depth…”’

Many artists have felt acutely this impossibility of finishing a work, but few have been so forthright in acting on that intuition. Bonnard’s was an art of flux. He eschewed the clear, well-defined forms of classical art to orchestrate a symphony of coloured blurs and smudges that only gradually add up to scenes of everyday life. Each patch of colour is, in itself, a distinct vibration, a different frequency, and, at the same time, each one communicates something of its own inner motion to all the others, little by little, as the eye moves back and forth among them. Each little area of colour ever so slightly jostles, not just the ones next to it, but any of those that can be seen in the same time frame – and therefore, potentially, every other patch of colour across the whole surface. Though the people, animals and things seen in the painting may not be in movement, the viewer’s perception of them is – it is constantly revising itself. To look at such a painting is to modify it, and to observe the modification is to prolong it. No wonder Bonnard couldn’t ever see his paintings as finished. They never were. They still aren’t. To look at them today is precisely to unfinish them – to maintain them in their state of incompletion.

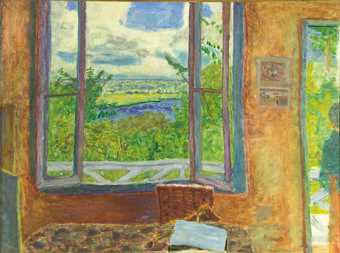

Pierre Bonnard, The French Window 1932, oil paint on canvas, 86 × 112 cm

Private collection

Vierny said something else that is very revealing: ‘Painters usually want a model to remain still’, she observed. ‘But he wanted me to walk all the time. Why? He never said. I didn’t push, because every artist has his own rhythm, and no one else can step into that rhythm. His rhythm was colour.’ Elsewhere, Vierny tells the same story slightly differently, mentioning nothing of walking; rather she speaks, simply, of movement: ‘He asked me to “live” in front of him, trying to forget he was there. He wanted at the same time life and absence.’ This makes clearer what one can, in any case, see in so many of Bonnard’s paintings: that the people he painted were neither holding a pose nor engaged in any strenuous effort, but simply going about their everyday lives at home. What is his wife Marthe de Méligny doing there in the lower-right corner of The French Window 1932? Stirring something in a bowl, perhaps, or grinding it with a pestle – it’s hard to be sure. In any case, she is absorbed in her task, seemingly without thought of all that surrounds her – all that we viewers can see in the greater part of the painting: not only the room in which she sits, but what is revealed through the big window on the left, a scene so vaguely defined, and yet legible, as land, trees, road, sky – and isn’t that the sea in the distance? What’s hard to understand is how the interior could be even more luminous than the world outside, lending a strange glow to the figure, especially her hair. Beyond this one sees, no, not a wall or another window but what one comes to recognise as a mirror reflecting (but as if at a great distance, almost further than the foliage seen through the window) the head of the man who observes her unnoticed, the painter himself. He is absent, in this moment, to Marthe – forgotten, ‘part of the furniture’, as the saying goes – and yet to see the painting is to be reminded of his presence, as marked by his perceptual and representational effort.

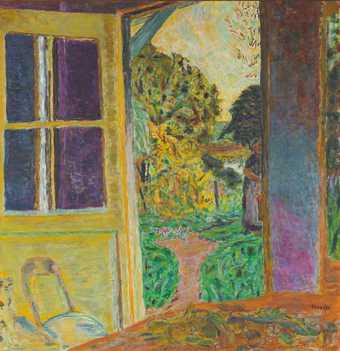

Pierre Bonnard, The Dining Room, Vernon c.1925, oil paint on canvas, 126 × 184 cm

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, photo: Ole Haupt

As The French Window suggests, the boundaries between inside and outside are, though not effaced, often very permeable in Bonnard’s art. Likewise, the distinction between person and place, actor and scene. So many are the works in which figures are there and yet nearly lost to sight, as if merging with the space they inhabit, or that inhabits them. A wonderful example of this is found in The Dining Room, Vernon c.1925, where one focuses straight off on the two figures (Marthe, again, and a boy) to the left. For one thing, the blue and green of their clothing presents a distinct contrast with the red of the wall (or possibly a painting) behind them. It takes a minute to register that there is a third player in this scene – another boy – who looks on from behind the open door, his face almost lost to view among the reflections on the door’s glass panes and the deep shadows behind it. One might almost say he was spying, though not on the two figures we first noticed, but rather on the scene’s other secret onlooker: the painter himself, in whose position one now finds oneself, as viewer. The composition seems to direct the viewer’s eye – past the seemingly vast oval plane of the table, on which a few scattered dishes appear to float as on a pond – towards the dazzlingly sunlit exterior on the right. It is in this direction that the boy on the left gazes, and to which Marthe, leaning forward, seems inadvertently to point; but the locus of self-consciousness in the picture is the half-hidden boy one almost fails to notice, the voyeur, the artist’s double.

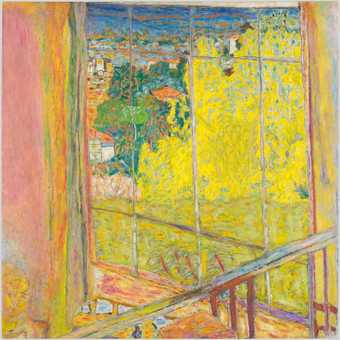

Pierre Bonnard, Fenêtre ouverte sur la Seine (Vernon) c.1911, oil paint on canvas, 78 × 105.5 cm

Courtesy Ville de Nice - Musée des Beaux-Arts Jules Chéret, photo- Muriel ANSSENS

Not every almost-absent figure in Bonnard’s paintings is necessarily a stand-in for the artist, and yet it’s hard to dismiss the feeling that any one of them might be. Fenêtre ouverte sur la Seine (Vernon) c.1911 uses its rust-coloured interior as a frame for the picture’s main event: the greens and blues of the lushly foliaged riverine landscape, which occupies the larger portion of the canvas and is echoed at the right edge by one more vertical slice of that scene, viewed through a doorway. Only there’s someone standing there, facing out towards the same terrain, of whom one glimpses just the left side. One can hardly say anything about this person except that he or she is there. It’s impossible to get a sure impression of an identity, and yet one has the feeling that this figure is looking intently, and that, in the intensity of this gaze, and in the otherwise strict unknowability of the person, Bonnard has invested something of his own desire for what Vierny called ‘life and absence’.

Pierre Bonnard, Door opening onto the Garden c.1924, oil paint on canvas, 109 × 104 cm

Private collection, courtesy of Jill Newhouse Gallery, New York

Another bisected figure is the aproned woman partially obscured by the door frame and glimpsed in the middle distance in Door opening onto the Garden c.1924. Perhaps she is a servant. The interest of this picture lies not in how the figure functions within it, but in the way that what is ostensibly an interior feels more like a landscape that happens to include some furniture. One could have expected the door on the painting’s left to indicate the way back in – not a way out. The notions of inside and outside are particularly permeable to each other here. What might be called Bonnard’s ‘pure’ landscapes are those without the play of inside and outside, domestic space and nature – something that is such a constant feature in those paintings seemingly of interiors. His landscapes are, of course, the paintings in which the figure is absent, or is even more underplayed than his interiors like Fenêtre ouverte sur la Seine (Vernon). One must keep in mind, of course, that in a work by Bonnard even the most subdued presence may not be merely incidental.

Pierre Bonnard, The Studio with Mimosa 1939–46, oil paint on canvas, 127.5 × 127.5 cm

Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais - © Bertrand Prévost

Pierre Bonnard, View of the River, Vernon 1923, oil paint on canvas, 48.3 × 45.7 cm

National Galleries of Scotland, photo: Antonia Reeve

Once the internal framing and architectural subdividing of the canvas that is typical of Bonnard’s interior/exterior paintings has been left behind, the scene migrates to ‘the great outdoors’. I am tempted to translate this as le grand dehors – a strange phrase that is not idiomatic in French but which the philosopher Quentin Meillassoux has used to describe all that is outside our conceptual grasp: ‘existing in itself regardless of whether we are thinking of it or not’. It is here that things get even wilder. Even the human may no longer be knowable: are those really swimmers splashing around in the water of Baigneurs à la fin du jour 1945? So the title tells me, but I could almost have taken them for outcroppings of rock, so obdurate is their rough material presence.

Pierre Bonnard, Baigneurs à la fin du jour 1945, oil paint on canvas, 48 × 68 cm

Courtesy Le Musée Bonnard, Le Cannet

The fact that things exist regardless of any human consciousness of them, regardless of whether one perceives them or not, is naturally beyond the power of any artist to present or represent. And yet, more than almost any painter I can think of, Bonnard at times seems to come close to at least suggesting such a thing. Compared to the people in his paintings, the figures in the work of other artists seem posed – no matter how casually they are represented. Their landscapes, likewise, seem to model themselves for the painter’s gaze. Bonnard’s landscapes are indifferent to the fact that they are being painted; he is ‘absent’ to them even more than he could ever possibly be to his family and friends while he painted them. The scene ‘lives in front of him’, in Vierny’s words, forgetting, so to speak, his presence – something that rarely happens in the case of other painters.

Maybe that’s why I feel, with regard to certain of Bonnard’s canvases, that I can neither ‘read’ them as representations nor consider them as incipiently abstract. For instance, although its trunk is pushed to the edge of the canvas, as is the case with so many of Bonnard’s human figures, I can still identify the palm tree at Le Cannet in the 1924 painting of that name – mainly thanks to the four fronds hanging down from the top of the picture. But what’s that piebald presence toward its centre, next to what must be the trunk of another palm tree further in the distance? Is it the dappled side of the same trunk, or a person – perhaps a woman in a long, mottled dress? Only a human being, I suspect, could be so out of order with its environment, but I can’t make myself see it as a figure, no matter how hard I try. And while the surrounding welter of greens and yellows and ochres answers well enough to my general idea of woods, I can’t for the life of me put a label on what’s happening at the painting’s right, where suddenly the woods cut away and some unsuspected distance is revealed, apparently a distant, blue hillside under an overcast sky – that is, I can see what it is but not how it can relate spatially to what’s manifest in the rest of the picture. It is simply an opening-up as dramatically in contrast to the rest of the painting as is the looming proximity of the trunk at the left. The painting doesn’t add up, and that not adding up is its truth.

Pierre Bonnard, Palm Tree at Le Cannet 1924, oil paint on canvas, 50 × 48 cm

Courtesy Manchester Art Gallery, UK / Bridgeman Images

Close enough to touch and yet somehow not quite graspable, Bonnard’s palm trunk puts me in mind of a poem by Wallace Stevens written three decades later, the title of which perhaps states his and the painter’s shared subject: ‘Of Mere Being’. The poet writes of ‘the palm at the end of the mind’, one that ‘stands on the edge of space’, blessedly indifferent to the one who happens to perceive it. For Stevens, poetry was essentially more sound than image, and so he placed in his palm tree ‘a gold-feathered bird’ whose song from within the palm is ‘without human meaning, / Without human feeling, a foreign song.’ For Bonnard the painter, the rhythm he could accept as beyond the human was colour – an endless, ever-changing song.

The C C Land Exhibition: Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory, is presented in The Eyal Ofer Galleries, Tate Modern, 23 January – 6 May. Curated by Matthew Gale, Curator (Modern Art) and Head of Displays, Tate Modern and Juliette Rizzi, Assistant Curator, Tate Modern. Supported by C C Land, with additional support from the Pierre Bonnard Exhibition Supporters Circle, Tate International Council and Tate Members. Organised in collaboration with Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, and Kunstforum Wien.

Barry Schwabsky is art critic for The Nation, co-editor of international reviews for Artforum and series editor for the Contemporary Painters series published by Lund Humphries. His recent books include Heretics of Language (Black Square Editions, 2018), The Perpetual Guest: Art in the Unfinished Present (Verso, 2016) and a collection of poetry, Trembling Hand Equilibrium (Black Square Editions, 2015).