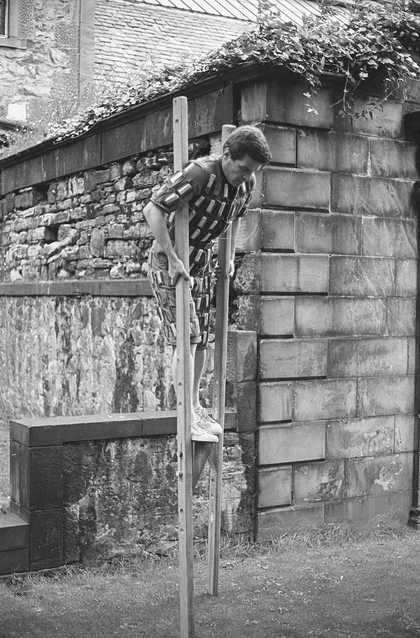

Paul Neagu performing Horizontal Rain in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh, 1971, photographed by George Oliver

© The Estate of Paul Neagu. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2018, courtesy Richard Demarco Archive

Paul Neagu (1938–2004) firmly believed that sight is not the only sense with which to encounter art – for him, taste, smell, touch and sound were just as important. He disrupted every assumption of what art could be. He made tactile boxes, edible sculptures, projects with fictional collaborators, and performances defying gravity. He conceived his exhibitions as experiments, while his writings spiralled through art history and philosophy. His works on paper were simultaneously preparatory works, documentation and independent artworks. Neagu was a generator of ideas, and he pulled on his experience and ambition to rethink the possibilities of sculpture and perception.

Neagu was born in 1938 in Bucharest, moving with his family to Timişoara in west Romania around 1946. On completing his baccalaureate in 1959 he trained as an electrician, based in the local power station. He later worked as a cartographer and topographer for the railway network, and became involved in stage design. Although his first choice of university study had been philosophy, he instead attended Nicolae Grigorescu Institute of Fine Arts in Bucharest, where the syllabus prioritised figurative painting. Neagu, though, was more interested in an art that generated encounters – for him it was sculpture, abstraction and cosmological forces that held the power to harness perceptions, not socialist realism. It was a time of discovery. He recalled that as an art student he befriended the librarian of the Union of Artists to gain access to the French art magazines forbidden to students, and remembered the wonder of seeing kinetic art for the very first time.

After graduating in 1965 his paintings expanded into three dimensions, and Neagu made boxes he described as ‘strange mixed media objects’. These were counter to state-supported art, and he would hide these from official view. In a communist state, a place to hide secrets would never find approval. Portable and scaled to the body, these were designed to be opened, pushed and pulled, demanding active, tactile encounters.

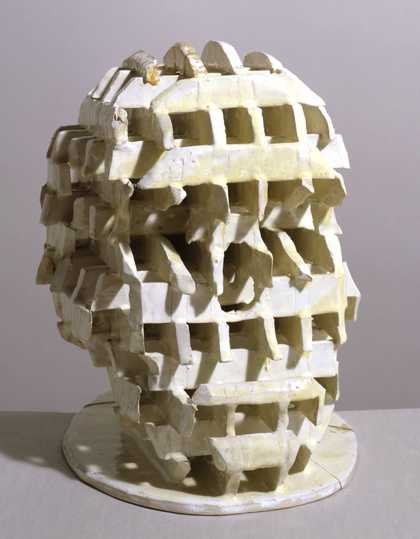

Paul Neagu

Ceramic Skull (1973)

Tate

Neagu chose materials resonating with his life and ideas, repeatedly working with leather, galena, mirrors and matchboxes – all easily accessible and cheap to source. His father was a shoemaker, and Neagu’s leather artisanship drew from this craft. Galena is a mineral capable of picking up radio waves, a property that Neagu had been experimenting with since a teenager – the kind of activity frowned upon by the totalitarian Romanian state. Mirrors encourage self-conscious looking: on encountering a reflective surface we find ourselves returning our own gaze – and either pausing to look longer or quickly moving to one side. Neagu was fascinated by making people aware of looking. Matchboxes also had a wider symbolic value for him. They fit both the pocket and the hand; they are cells that can be built into ever-expanding temporary structures inviting touch. As Neagu noted: a cell is both a prison and an ‘energy centre, a place in which energy is conserved for future use’. He frequently used the term anthropocosmos to convey the individual human as a universe made of interrelating cells.

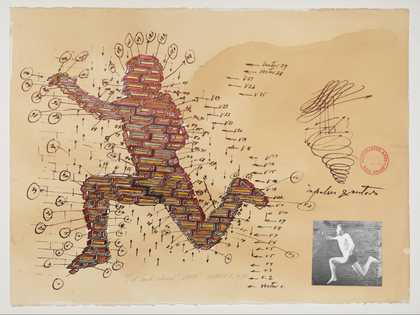

Paul Neagu

Jump (1977)

Tate

In 1969 Neagu published his Palpable Art Manifesto. This prescription for making and perceiving art pronounced: ‘The eye is fatigued, perverted, shallow, its culture is degenerate, degraded and obsolete’. This anti-ocular invective accompanied his first British solo exhibition Art in a Dark Room at Edinburgh Arts Festival. The gallery walls were painted black, speakers emitted twittering noises, and the artist was often found lurking in the corners, observing. Boxes hung from the ceiling; visitors were invited to touch, open, and push them so they

fell to the floor. This trip to Scotland, under the wing of gallerist Richard Demarco, was followed by more invitations and in 1971, as Neagu described: ‘I went to the Home Office and declared myself ready for asylum.’ Six years later he obtained British citizenship, not returning to Romania until the fall of communism in 1989.

In the ensuing four decades Neagu – who passed away in 2004 – became a vital part of the story of British art. He taught at Hornsey, Slade, Chelsea and Royal College schools of art, with his students including Antony Gormley, Anish Kapoor and Rachel Whiteread. He opened the Gallery of Generative Art in his London flat, exhibited at Bristol’s Arnolfini, Modern Art Oxford, the Serpentine Gallery and the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London. His first London exhibition took place at Sigi Krauss Gallery, which was filled with a sweet smell emanating from the human-sized, edible sculpture made of waffles stacked eighty high and linked with cream. The exhibition invitation explained Cake-Man would be ‘offered for distribution on May 10 1971 from 6pm onwards.’ Each attendee was allocated a section with a personalised note and invited to consume the piece on site. This really was palpable sculpture.

Paul Neagu performing Gradually Going Tornado at the Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh, April 1975

© The Estate of Paul Neagu. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2018, courtesy Richard Demarco Archive

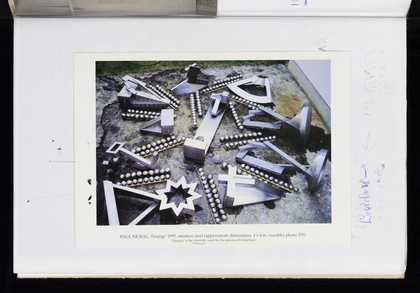

In 1977 Neagu left performance behind, his event-based works of the first part of the 1970s having seen him variously whirl around on roller skates and impossibly run up a wall. He turned to concentrate on the development of a sculptural form he called Hyphen. This three-legged sculpture is reminiscent of a plough, a crouched animal and a cartographer’s compass. Seen by Neagu as the culmination of his research, Hyphen was repeated in many sizes and media, and became a part of his final body of ever-expanding work: Nine Catalytic Stations, which preoccupied the artist through the 1980s to the time of his passing. This circle of nine sculptures, like all of Neagu’s artworks, is a call to perceive with greater acuity and to think about how we humans understand our complicated place in the world.

Paul Neagu, Anonymous

Page 30 (1968–2002)

Tate Archive

© The estate of Paul Neagu. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2026 & © reserved

A selection of work by Paul Neagu, curated by Juliet Bingham, Curator, International Art and Valentina Ravaglia, Assistant Curator is on display at Tate Modern until 24 November.

Lisa Le Feuvre is Executive Director of the Holt-Smithson Foundation in Santa Fe, New Mexico.