Grace Pailthorpe and Reuben Mednikoff, from a photograph album of the couple in America and Canada, 1941–5

National Galleries of Scotland. Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art Archive

When Grace Pailthorpe (1883–1971) and Reuben Mednikoff (1906–1972) first met at a party in London in January 1935, nobody could imagine they were to become among the most intriguing and controversial figures in the history of surrealism.

Reuben Mednikoff, aged 29, was a young poet and artist who was fascinated by what he was hearing and reading about surrealism. Pailthorpe, aged 52, remarkably a surgeon in the First World War, had been researching the psychological treatment of juvenile delinquency, refuting the efficacy of incarceration and seeing the exploration of the offender’s unconscious as a way to solve their conflicts. While working in Birmingham Prison she included delinquents’ artworks in her treatment to test the prisoners’ faculties of recognition, imagination and apperception (making sense of an idea by integrating it with those one already holds).

From the day the couple met they were rarely apart, Mednikoff teaching Pailthorpe the rudiments of art, she teaching him the basics of interpretative analysis. This unique 35-year-long collaboration produced a phenomenal number of drawings and paintings, with Pailthorpe in the role of a surrogate mother haunted by the trauma of birth-giving and Mednikoff acting as a ‘guinea pig’ and trying to come to terms with what could be described by psychoanalysts as his anal-sadistic tendencies and postnatal obsessions.

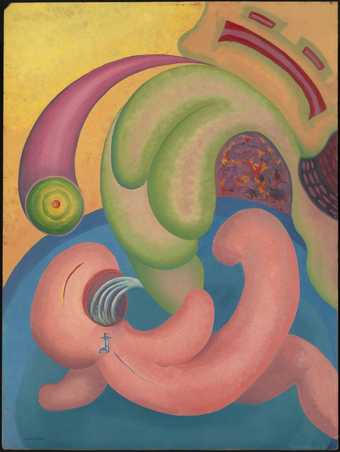

Reuben Mednikoff

December 31, 1937, 8.00pm (Oompah) (1937)

Tate

After settling in a cottage in Port Isaac in July 1935, they were invited by Roland Penrose to participate in the June 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition. They stunned the public with their somewhat nightmarish visions. André Breton, founder and chief arbiter of the surrealist movement in Paris, saw in their exhibits ‘the best and most truly surrealist of the works by English artists’.

From 1936 to 1940, they participated in the activities of the British Surrealist Group. Their first exhibition took place at the Guggenheim Jeune gallery in London (run by Peggy Guggenheim) in January 1939 and they were due to take part in the June 1940 Surrealism Today exhibition at the Zwemmer Gallery but had just been expelled from the group after Mednikoff tried to organise a meeting to redefine the role of surrealism in wartime England, a move seen by the actual leader of the group, E.L.T. Mesens, as a personal attack. Due to this split and the outbreak of war in Europe the pair decided to leave England, settling in New York, then California and, in 1942, moving to Vancouver where they developed the discourse of surrealism through lectures, radio talks, newspaper articles and the first-ever surrealist exhibition in Canada.

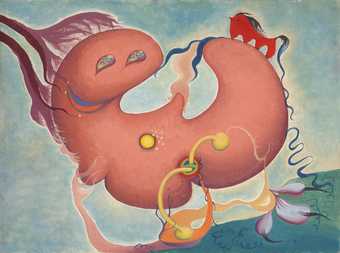

Grace Pailthorpe

December 4th, 1938 (1938)

Tate

In the December 1938 to January 1939 issue of the London Bulletin, Pailthorpe published an article titled ‘The Scientific Aspects of Surrealism’, which initiated a resounding controversy: weren’t they more scientific than surrealist? Even if they were first recognised as surrealist by Breton, Yves Tanguy, Salvador Dalí and Wolfgang Paalen, Pailthorpe’s insistence on the therapeutic value of their works, as shown by the clinical comments accompanying each painting or drawing, seemed to run counter to surrealism’s praise of the subversion of logic. (Their collaboration broke with conventional analytical practice, however: their cross-analysis of each other and swapping of roles implied an absence of hierarchy or difference between the analyst and the analysand.) Repeatedly, according to their respective interpretations of each other’s imagery, infantile fantasies were opened up: in Mednikoff’s works representations of the release of excremental and spermatic liquids, blood and vomit were read as articulating the child’s answer to the father’s tyranny; in Pailthorpe’s works gaping wombs, eggs clinging to tentacles, umbilical cords encircling breasts were seen to alternate with happy foetuses in intrauterine Eden-like spaces. As Werner von Alvensleben, a psychoanalyst, and Parker Tyler, a New York poet, remarked and stigmatised in the next issue of the London Bulletin, these were ‘literal explanations’, ‘schoolroom exercises’ averse to surrealism’s celebration of irrational thought processes.

Grace Pailthorpe

May 16, 1941 (1941)

Tate

Still, as Pailthorpe had put it in her article, they and the surrealists did share the same concept of the ‘liberation of mankind from all fetters which prevent full expression’ – that is, from bourgeois repression. Pailthorpe and Mednikoff achieved this almost unwittingly, not by what they painted or analysed in writing – fantasies whose exploration had a curative aim – but by how they charted the unconscious visually. Indeed, the contrasting use of pale and garish colours, the fluidity, dissemination and irrational profusion of entangled organic shapes creates a kind of illegible, and thus liberating, whirl, which by the late 1940s Pailthorpe preferred to call ‘psychorealism’ rather than surrealism. With its marriage of the aesthetic and the scientific, she found her concept more ‘constructive’ in its pursuit of true social liberation, though she never underrated the uncontrollable psychic energy that runs between the conscious and the unconscious and creates fragmentation in the subject, whether the artist or the viewer. After returning to the UK in 1946 Pailthorpe worked as a consultant psychiatrist at the Portman Clinic in north London, with Mednikoff as her assistant, until 1952. They also ran a school of art therapy in Dorking and underwent a phase of mysticism and occultism. The eeriness of their relationship reached an apex when, in 1948, she decided to adopt Mednikoff as her son. He changed his name to Richard Pailthorpe and called her ‘Mother Flower’.

Grace Pailthorpe

April 20, 1940 (The Blazing Infant) (1940)

Tate

Grace Pailthorpe and Reuben Mednikoff’s artworks from the Tate collection are included in the exhibition A Tale of Mother’s Bones: Grace Pailthorpe, Reuben Mednikoff and the Birth of Psychorealism, curated by Dr Hope Wolf with Rosie Cooper, Martin Clark and Gina Buenfeld, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, 6 October 2018 – 20 January 2019, and Camden Arts Centre, 12 April – 23 June 2019.

Michel Remy is Professor Emeritus of English Literature and Art History at the University of Nice, France. His most recent book is Eileen Agar: Dreaming Oneself Awake, published by Reaktion Books.