Edward Burne-Jones, Love among the Ruins 1870–3, watercolour, bodycolour and gum arabic on paper, 96.5 × 152.4 cm

Photo © David Parmiter

The name Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) may not be as familiar today as it once was, but his art is all around us. His stained-glass windows illuminate churches all over the country with their evocative shapes and rich glowing colours; his paintings stand out in our art galleries and museums through their beauty of craftsmanship and design; and at Christmas time the artist’s distinctive melancholy angels can be seen on many a greeting card. Burne-Jones is the most easily recognisable of artists. To describe someone as possessing ‘a Burne-Jones look’ is to conjure up a vision of a thin, pale youth with a dreamy expression: it is an androgynous type of beauty that is disturbing yet fascinating to behold, and has influenced a growing appetite for fantasy, from Tolkien to Game of Thrones.

Despite such trademark features, Burne-Jones is also the most elusive of artists. The myths and legends that inspired so many of his creations – from the quest for the Holy Grail to the Sleeping Beauty – have become part of our culture, but that does not make his art any easier to understand. There is a strangeness to his vision that lifts it beyond illustration into the realm of mystery. Take The Golden Stairs 1880, for example, a painting that has been on almost permanent display since it entered the Tate Gallery in 1924. Here, a group of near-identical maidens, draped in white and holding a variety of musical instruments, tread in trance-like fashion down a spiral staircase into a courtyard, the purpose and significance of their movements unknown.

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt

The Golden Stairs (1880)

Tate

The same could be said of The Mill 1870–82 in which three women dance to the sound of a musician while nude male bathers pose eerily in the background. In one of the artist’s most celebrated compositions, Love among the Ruins 1870–3, a woman stares bleakly into the distance as she clings to her male companion in the shell of a briar-covered ruin. In all these pictures, figures are shown revolving and turning, serving no purpose other than to highlight a mood of stillness and inertia, the suspension of action underscoring the essential ambiguity that made Burne-Jones’s art so baffling to his contemporaries, and which continues to haunt us today.

Part of the mystery is the artist himself. He began life as plain Edward Jones from Birmingham, rising to become Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Baronet, lauded throughout Europe as the greatest artist to have ever emanated from Britain, and a figurehead for symbolist artists such as Fernand Khnopff in their rebellion against the materialist values of modern times. Despite his fame and celebrity Burne-Jones felt uncomfortable in the public eye. Instead he immersed himself in his works in the studio at his family home, the Grange in Fulham (demolished in the 1950s), periodically giving way to the bouts of depression and solipsism that plagued him throughout his life. Even here he was restless and sought an outlet for his frustrations and emotions in the intimate friendships he developed with a number of high-society women, sometimes writing up to five letters a day to a special soul mate, pouring out his feelings. Many of these letters he enlivened with caricatures that were invariably self-deprecating and often cruel in their humour (he had a particular preoccupation with large women, who both frightened and intrigued him).

The enigma of Burne-Jones would explain why he has been the subject of fascination for a series of biographers who have all been drawn to the extremes and contradictions of his personality. For the aesthete and painter Walford Graham Robertson, who knew the artist personally, Burne-Jones was ‘Puck beneath the cowl of a monk’, apt to change in a flash from being grave and priestlike to appearing mischievous like a child. More recently, Fiona MacCarthy has described him as ‘maddeningly evasive’ and impossible to pin down except, perhaps, through his work, which discloses a pessimism and weirdness of vision with its erotic dreaminess and sad sense of estrangement.

Edward Burne-Jones, The Love Song 1865, transparent and opaque watercolour on paper, 54.9 × 77.7 cm

© 2018 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Even the artist’s wife, the faithful and long-suffering Georgiana, had difficulty in communicating what her husband actually believed in, apart from his art. Her Memorials (1904), written shortly after the artist’s death, paint a picture of a man who was deeply versed in the Bible and theology, but lost interest in formalised Christianity. While holding strong ethical views – he felt indignant at Britain’s treatment of other races and cultures, and was sympathetic with the underdog – he refused to become politically engaged. Such aloofness, she hints, set him apart from his life-long friend and collaborator, William Morris, who became, by contrast, a committed socialist and activist.

As an artist Burne-Jones was unusual in coming to his profession from a literary and intellectual background rather than a practical one; he was educated at a university, not an art school. From his early years he had a strong interest in literature, developing a passion for the classical myths, the medieval romances of Malory and Chaucer, and the writings of modern writers such as Tennyson and Browning. These literary inclinations he applied to his art by crafting his compositions in an analytical manner, similar to the way a scholar might approach a literary text – scrutinising, editing and refining each part in building up a design. Instead of working spontaneously, his finished works evolved over many years from his seemingly endless generation of preparatory drawings, which extended from sketches to full-scale cartoons; these encompassed numerous studies for body parts and ancillary features: heads, hands, feet, draperies, armour, plants, birds – each drawing a work of art in its own right.

In defiance of the methods taught in art schools about the proper way to use materials, Burne-Jones developed his own idiosyncratic practice by disregarding the intrinsic properties of a medium and following his own instincts. All his works, whether executed in watercolour, oil pastel or chalk, appear heavy, jewel-like and opaque, and in terms of their weight and texture were often compared to relief sculpture or tapestry. In this, his aim was to create something solid and permanent that formed part of a fixed environment rather than existing as a free-floating commodity to be sold on the art market, which he professed to despise. Although he did not follow Morris into politics, he was one with him in wanting to create an art that served everyone, rather than a privileged elite. As he once said: ‘I want big things to do and vast spaces, and for common people to see them and say Oh! – only Oh!’

It followed that Burne-Jones valued the applied arts (or the ‘lesser arts’ as they were termed) and the fine arts equally, and was united with Morris in believing that decorative forms, such as stained glass and mosaic, were more democratic in their reach and appeal. In seeking to embrace a broad audience he depicted stories and legends that could resonate in the popular imagination while being beautiful and mysterious to behold. His was a public art that required a deep, personal level of engagement.

Although the subject matter of Burne-Jones’s art looked back to the past, being largely indebted to the Bible, mythology and Renaissance culture, his treatment of these themes was strikingly modern on account of its troubling psychology and intense mood of introspection (it only just predates Freud). The strange aspects of style that made his works appear so unconventional in the 19th century (the non-hierarchical ordering of composition and the disturbing combination of flat and illusionistic shapes, for instance) could also be seen to give it a contemporary edge.

Edward Burne-Jones, The Doom Fulfilled, 1888, oil paint on canvas, 155 × 140.5 cm

Courtesy Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

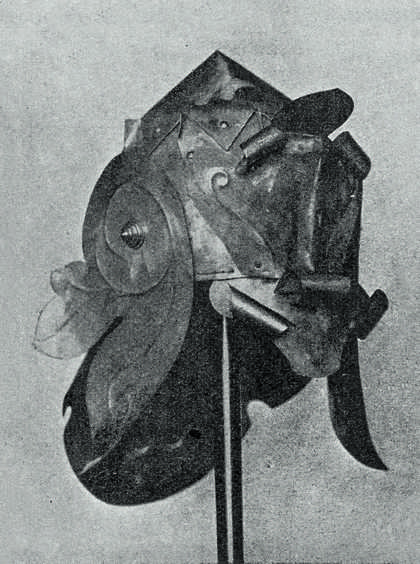

Burne-Jones was not a realist, preferring, as he said ‘to forget the world and live inside a picture’. In creating the imagined environments of his pictures, he worked at a remove from the existing world, designing the objects that were to appear in his works and then having them fabricated as three-dimensional models, so, once painted, they existed as ‘a reflection of a reflection of something purely imaginary’. This kind of practice not only finds an echo today in the computer-aided design that gives science-fiction and fantasy film its own compelling but unbelievable reality, but also in the methods adopted by some conceptual artists. The detailed paper and cardboard constructions made by Thomas Demand, which the artist then photographs to create something elusive and romantic, find a parallel in the strange pieces of armour, furniture and weaponry Burne-Jones had assembled in his studio to be copied into his art.

Models designed by Edward Burne-Jones for King Cophetua's shield in his painting King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid 1884 and King Arthur's breastplate in the 1895 play King Arthur at the Lyceum Theatre in London

Model designed by Edward Burne-Jones for Perseus's helmet in the Perseus series commissioned in 1875

Another echo is found in the work of painter Elizabeth Peyton, whose slender, sexually ambiguous figures and decorative experimental brushwork are reminiscent of Burne-Jones. In acknowledging the relationship, Peyton has even produced her own version of the artist’s sleeping knights from the Briar Rose 1885–90 series. Here the abstracted rhythms of the contorted, somnambulant bodies appear to transpose Burne-Jones’s unquiet soul into the contemporary era.

Edward Burne-Jones, curated by Alison Smith with Tim Batchelor, Assistant Curator, Tate Britain, supported by Tate Patrons and Tate Members, Tate Britain, 24 October – 24 February 2019.

Alison Smith is Chief Curator, National Portrait Gallery. She was previously Lead Curator, 19th-Century British Art, Tate Britain from 2000 to 2017.