Pablo Picasso, Woman in a Red Armchair 1932, oil paint on canvas, 144 x 112 cm

© Succession Picasso/DACS 2018, courtesy Musée Picasso

Woman in a Red Armchair is one of the paintings that has most influenced me. It led me to reconsider how the human figure could be constructed – by using the methods of the old masters, and then radicalising that language by introducing contemporary images from my own imagination.

Picasso uses the concept of volume to create an assemblage of bone-like forms that fall within the existing shadows and depths of the red armchair, producing a masterpiece of warm, figurative abstraction located in space. This piece is the sum total of Picasso’s so-called ‘Dinard’ sketchbooks, finally realised in their most complete essence. The volume of the forms captured at the seaside town – boulders, bones, pieces of wood, sticks and stones – all suggest sculptural figures.

In 1932, with another seated figure of a woman in a red armchair (the light lavender tone is reminiscent of the one used in the paintings of Marie-Thérèse), Picasso left his neo-classical phase behind, taking his art back to the 16th and 17th centuries. He began to view the works of Rembrandt, Velázquez, David and Cranach not just as paintings, but also subject matter that he would introduce into his works, starting in the 1950s and continuing until the end of his life.

The paintings that Picasso began to produce in the 1930s certainly go beyond any simplistic rendering of any particular person. Rarely did he title a painting by the name of its model. In Woman in a Red Armchair, his use of chiaroscuro, in some remote way, mirrors both the light and depth seen in early baroque paintings, such as Caravaggio’s Youth with a Ram 1602. Picasso’s work seems also to be a reconfiguration of Caravaggio’s painting – whether subconsciously or intentionally, one can only postulate. On comparing elements of Picasso’s painting with the boy’s red robe, his body’s physical position, the form’s light and volume, as well as the head of the ram, one can see evidence of the same parts and pieces played out in an entirely different manner.

Reconfiguration has played an enormous role in my own paintings: a work that seems to have nothing to do with the final product is in fact its origin – such as David’s portrait Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier and His Wife 1788 and my work The Insane Cardinal 2003. These ideas somehow come from a reverse construction, rather than the deconstructive method of work most commonly associated with Picasso.

All this said, I believe Picasso’s greatest influence on me has nothing to do with his actual paintings, because they are, I think, untouchable. It is rather his way of thinking – the freedom of his approach to imagery, and its further potential. This has liberated me from the historical placement, or chronological order, of time, revealing the infinite possibilities of an interchangeable sense of time on the journey towards a new plastic form, one realised by the appearance of a presence from an original source. This process of transforming or reassembling a new image from the parts and pieces of a work’s initial material form is, I believe, key to understanding that work’s relativity and its influence in art.

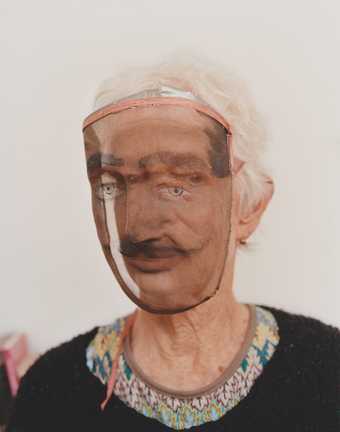

George Condo, Seated Girl in a Green Chair 2007, oil paint on canvas, 109.2 x 97.8 cm

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2018, courtesy the artist

George Condo is an artist who lives and works in New York. A selection of his works are on display at Tate Modern.