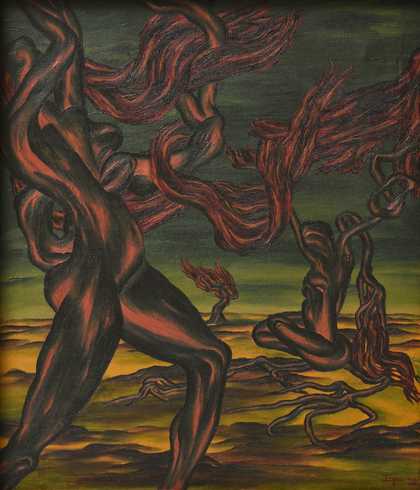

Inji Efflatoun, Surrealist Composition 1942, oil paint on canvas, 71 × 60.5 cm

Private collection, photo © Viken Seropian

On 22 December 1938, some 37 painters, writers, photographers, journalists and lawyers in Cairo signed a message of solidarity to fellow artists and intellectuals living under totalitarian regimes in Europe. The group included men and women, those of Muslim, Christian and Jewish backgrounds, long-term foreign residents and nationals. Titled ‘Long Live Degenerate Art’, the manifesto was printed in French and Arabic and condemned the recent, infamous Nazi exhibitions of so-called degenerate art. It likewise denounced similar attempts at stifling anti-national and anti-racialist art in Italy. The text carried a reproduction of Guernica 1937, Picasso’s celebrated denouncement of atrocities suffered by civilians during the Spanish Civil War.

Hassan El-Telmisani, Untitled 1946, oil paint on double-sided canvas, 50 × 39 cm

El-Telmisani family, Cairo, photo © Hesham Salama

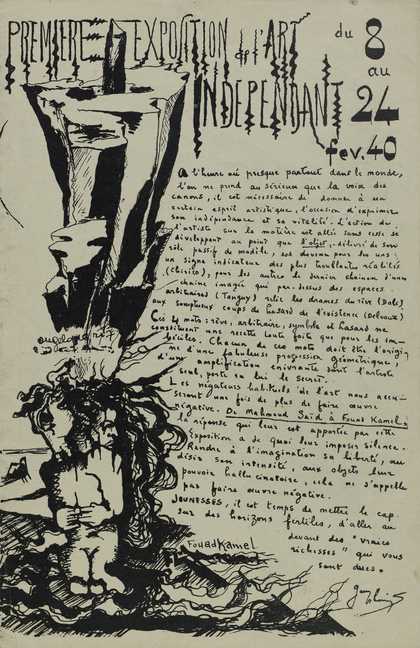

The most significant group to emerge in wartime Egypt was Art and Liberty (Art et Liberté or jama’at al-fann wa al-hurriyyah). Inaugurated in Cairo on 19 January 1939, it counted among its members many of the signatories of the 1938 manifesto. Led by the francophone Egyptian poet Georges Henein, founding members included artists such as Kamel El-Telmisany and Ramses Younane, alongside other self-styled intellectuals and activists. The group was profoundly politically engaged, the visual arts being just one strand of their endeavour. Over the course of the war, they would organise five exhibitions of ‘free art’ (art indépendant, or al-fann al-hurr), along with a series of political and cultural journals featuring news, editorial and artwork.

Members of the Art and Liberty group during their 1941 exhibition. Front (left to right): Jean Moscatelli, Kamel El-Telmisany, Angelo de Riz, Ramses Younane, Fouad Kamel; back (left to right): Albert Cossery, unidentified, Georges Heinen, Maurice Fahmy, Raoul Curiel

© Sylvie and Sonia Younan collection, Paris

As the son of an Egyptian diplomat, Henein had spent significant periods of his youth and early adulthood in Rome, Brussels, Madrid and Paris. He joined the surrealist movement in 1934 and struck up a correspondence with its founder, André Breton in December 1935. Henein’s enthusiasm for surrealism surfaced in a manifesto-like statement titled ‘On the Aesthetic’, published in Un Effort in January 1936, which positioned the history of art in Egypt within the internationalist framework of surrealism. In the same period, photographer and surrealist muse Lee Miller arrived in Egypt as the wife of a wealthy Egyptian businessman. She connected with Henein and seems to have actively promoted surrealist ideas within Cairene intellectual circles. Miller’s then lover, Roland Penrose, also played a role in introducing Art and Liberty to English surrealists, publishing an announcement of the group’s formation and a copy of the manifesto in the April 1939 issue of the London Bulletin.

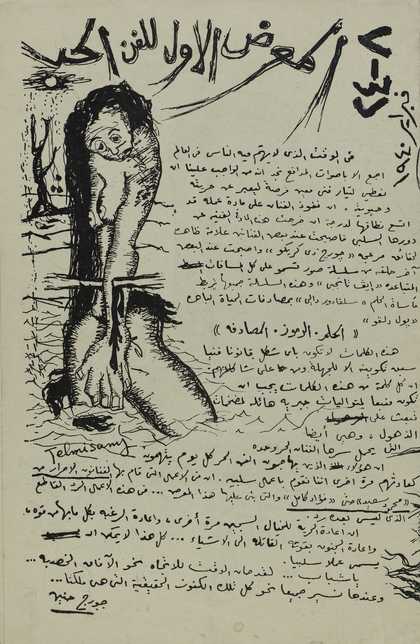

Front cover of the catalogue for the first Art and Liberty exhibition in 1940, with text by Georges Heinen and drawing by Kamel El-Telmisany

Centre Pompidou, Paris, MNAM-CCI, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Sylvie Younan gift, 2015, photo © Centre Pompidou, Paris / Anne Paounov

Back cover of the catalogue for the first Art and Liberty exhibition in 1940, with text by Georges Heinen and drawing by Kamel El-Telmisany

Centre Pompidou, Paris, MNAM-CCI, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Sylvie Younan gift, 2015, photo © Centre Pompidou, Paris / Anne Paounov

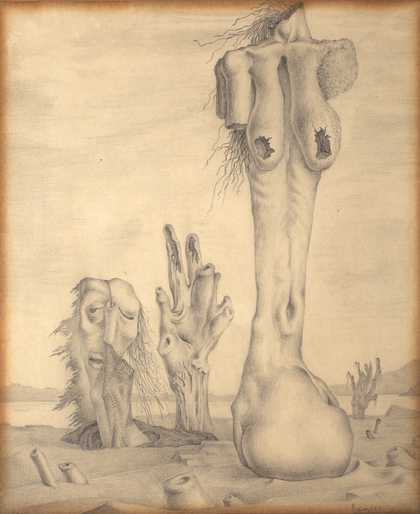

While many works of art associated with Art and Liberty have been destroyed and/or were not intended to survive, those that remain – primarily paintings and drawings – reflect a variety of styles and artistic frames of reference, prominent among them Georges Rouault, Yves Tanguy and Pablo Picasso. At the same time, many works feature scenes, sites and social types associated with Egypt’s rural poor and, most commonly, with the country’s urban popular classes, pointing to various forms of social and economic injustice and violence wrought upon the local landscape and its people.

In Kamel El-Telmisany’s paintings in gouache and oil of Cairene prostitutes, for example, the women’s faces and bodies are not the subjects of the careful study afforded the academic nude, but tend, rather, towards the cartoonish or the grotesque. In other instances, such as Aida 1940, a trompe l’oeil effect is achieved when a painted stake appears to plunge into a portrait, as if to suggest that even normative images of women, such as society portraits, could not escape the violence of the patriarchal gaze. Telmisany explored similar motifs in oil paintings produced in the same period, and a drawing of his appeared inside the catalogue of the first exhibition organized by Art and Liberty, alongside a text authored by Henein. Rather than evince the picturesque quality of the Egyptian rural landscape or the sanctity and integrity of the Egyptian body, Telmisany, as well as other members of Art and Liberty, such as Ramses Younane and Fouad Kamel, presented (primarily female) bodies in a state of decay or deflation, shattered and incomplete: pointing to the inscription of violence on the social body.

Ramses Younane, On the Surface of the Sand c.1939, pencil on paper, 27 × 22.5 cm

Museum of Modern Egyptian Art, Cairo, photo © Nabil Boutros

Up until 1946, group members of Art and Liberty developed a sophisticated critical response to the artistic, social and political status quo of interwar Egypt and Europe. Indeed, their anti-nationalist stance led to their marginalisation within establishment accounts of Egyptian art history. As a result, their powerful influence on subsequent generations of artists remains controversial to this day. Art and Liberty was dismissed in its time and would later be alienated from its surrounding cultural and social realities by art historical sources. It would, however, prove highly influential in the emergence of a generation of artists who were subsequently embraced by a post-1952 nationalist historiography as constituting the first authentic school of Egyptian modern art.

Laurent Marcel Salinas, Birth 1944, oil paint on cardboard, 16.5 × 22 cm

© Laurent Marcel Salinas Estate, New York, photo: rogallery.com

Surrealism in Egypt: Art et Liberté 1938–1948, Tate Liverpool, 17 November – 18 March 2018. The exhibition is curated by Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath of Art Reoriented in collaboration with Kasia Redzisz, Senior Curator and Tamar Hemmes, Assistant Curator, Tate Liverpool.

Clare Davies is Assistant Curator Modern and Contemporary Art, Middle East, North Africa and Turkey, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.