Mrinalini Mukherjee with her jute sculpture Woman on a Swing in 1989

Mrinalini Mukherjee’s pedigree may have predisposed her towards an artistic practice. Born in Mumbai in 1949 as the only daughter of artists Benode Behari and Leela Mukherjee, the sculptor grew up with intimate access to an enviable milieu of cultural practitioners, including KG Subramanyan, who considered Behari a mentor. Fortuitously, Subramanyan became Mukherjee’s mentor decades later, when she was pursuing her post-diploma degree in mural design at MS University, Baroda, from 1970 to 1972, after having studied painting for the preceding five years.

Her figurative painting background notwithstanding, Mukherjee (1949–2015) found herself intuitively drawn to sculpture, perhaps on account of her lack of training in the subject, which, she believed, translated to an irreverent ignorance about the medium’s limitations. By the time she graduated, she had already discovered jute ropes during an annual fair in Baroda, finding in them a viable material for the organic sculptures she sought to create. In 1978, she was awarded the British Council scholarship for culture, which allowed her to study at West Surrey College of Art and Design in Farnham, UK. There, Mukherjee continued her daring experimentation with dyed hemp.

Her fibre sculptures were the result of a painstaking process, which meant she could produce only one or two a year. ‘Almost yogi-like, Mukherjee dedicated herself, especially through the 1980s and early 1990s, to creating, and re-creating, in dyed and woven hemp, rather figurative sculptures that evoked ancient, wizened spiritual beings,’ wrote journalist Elizabeth Kuruvilla in her obituary for Mukherjee after her unexpected death at the age of 65 in February 2015, a week after the opening of her most significant 90-piece retrospective at the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi. Transfigurations, curated by Peter Nagy, brought together Mukherjee’s early figurative, erotic hemp sculptures, placing them in close proximity to her later ceramics and bronzes. ‘It is astonishing how the manually made knot that is the basic micro unit of the sculptural syntax of her works in rope fibre could yield such baroque and imposing floral and arboreal totems,’ noted art historian Deepak Ananth in his own elegy for Artforum. ‘Their suggestive folds and rents, protrusions and openings, are poised at the wondrous moment that precedes a dehiscence.’

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Ritu Raja 1977, woven hemp fibre, 190 x 82 x 50 cm

Courtesy Jhaveri Comtemporary, Mumbai

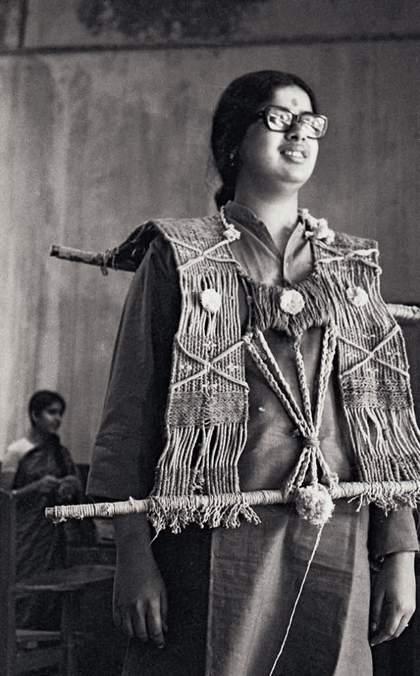

Mrinalini Mukherjee wearing one of her fibre works during preparation for the Fine Arts Fair at MS University, Baroda in 1969

© Jyoti Bhatt, courtesy Asia Art Archive

By the mid-1990s, Mukherjee had begun to gravitate towards ceramics. At first she experimented with papier mâché during a residency at the Sanskriti Kendra in 1995, but was disappointed by its lacklustre quality when dry. Also present were Dutch artists Rob Birza and Bastienne Kramer, who introduced her to the immediacy of clay and the terracotta medium. In 1996, thanks to a residency at the European Ceramics Work Centre, ’s-Hertogenbosch, Holland, Mukherjee began to acquaint herself with ceramics, gradually compelling the medium to extend its own limitations. ‘There they don’t discourage you from doing anything,’ she told me in an interview in her apartment in 2013. ‘You may want to do the impossible; they won’t tell you not to do it, they’ll tell you how to start.’ She would return to the Centre in 2000, where she created her Night Bloom series, a manifestation of her childhood fascination with botany.

In the early 2000s, Mukherjee was still making her dyed hemp sculptures, but her work would change as her mother’s health deteriorated. ‘When my mother was very ill, I had to sit in the hospital with her, so the work had stopped,’ she told me. ‘After she passed away, I didn’t feel like sitting at home and knotting this rope and I started going to Garhi [an artist studio complex in New Delhi]. I wanted to do something which was immediate, so I started working with wax, and then made some nine to ten pieces in this red wax – all very beautiful and delicate – but then summer started happening; the wax started melting, these things started losing their form. Now the only option was to cast it,’ she said during our interview.

Mrinalini Mukherjee, Palm-Scape VI 2013, bronze, 134 x 91 x 33 cm

Courtesy Nature Morte, New Delhi

Mukherjee was warned by senior sculptors that details wouldn’t transfer in the casting. But she was undeterred, preferring to see the results for herself. ‘Some things came and some things didn’t, and I didn’t mind that element. In the beginning, you get disappointed that all this red, transparent, translucent wax becomes like this solid thing, but slowly you learn not to look at the wax as the beautiful thing. I know what’s going to happen with it and so I start to plan it that way,’ she explained, when we spoke soon after the opening of her two solo shows, Palm-Scapes and Bronze, at Delhi’s Nature Morte gallery and Mumbai’s Jhaveri Contemporary respectively in 2013.

At this time, Mukherjee, no loyalist to material, wasn’t sure whether she would continue with bronze. She had expressed amusement about the critical ambiguity concerning her choice of medium. ‘First they had a hang-up about “is this craft or is this art”,’ she had said. ‘Finally, it got more accepted as sculpture in the West. Then they think, “Oh, you’re still doing that rope thing”, but when you’re not doing the rope thing, everybody wants you to do that... Or somebody will come and say, “Oh, so you eventually went back to bronze” but, you know, I didn’t go back to bronze. I never trained as a sculptor – I trained as a painter, so I was not taught all this in art school, so I have no preconceived notion about it. I can’t say I’m going to do this for the rest of my life. Till I have the opportunity to do it, and I have a new idea, I’ll do it. Then maybe you start working in watercolours on paper?’ she said, her speech punctuated by either a constricted cough or nonchalant laughter.

Mukherjee’s retrospective featured a poignant moment in which her earliest hemp work, Waterfall 1975, and one of her more recent bronzes, Big Flower 2014, faced each other, demonstrating her uncanny sculptural imagination. Present, too, was her latest bronze work, Palm-Scape IX 2015, which, as critic Meera Menezes noted in Artforum, ‘resembles a date palm petrified in molten metal and offers a bursting efflorescence’. It still seems unimaginable that it was to be among her last.

Mrinalini Mukherjee's Jauba 2000, was presented by Amrita Jhaveri in 2013, and Ritu Raja 1977 was purchased with funds provided by the South Asia Acquisitions Committee in 2017.

Rosalyn D'Mello is the author of A Handbook for My Lover (2015) and former Consultant, Research and Archives at Nature Morte, New Delhi. She lives in New Delhi.