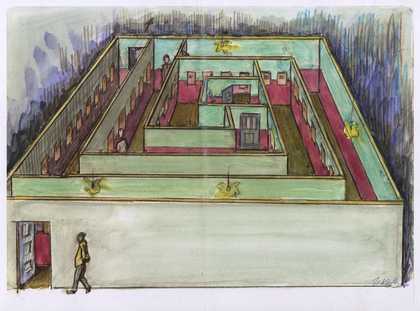

Drawing for Ilya Kabakov's Labyrinth (My Mother's Album) 1990

© Ilya & Emilia Kabakov

I was already a curator and art adviser in New York when I started working with Ilya Kabakov, who had left the Soviet Union for the first time in 1987 for exhibitions in Europe and the US, before settling in New York in 1992. Ilya had matured as an artist in the Soviet Union, so Soviet visual culture – from children’s books to propaganda posters – was very familiar to him. It shaped his and generations of artists’ work.

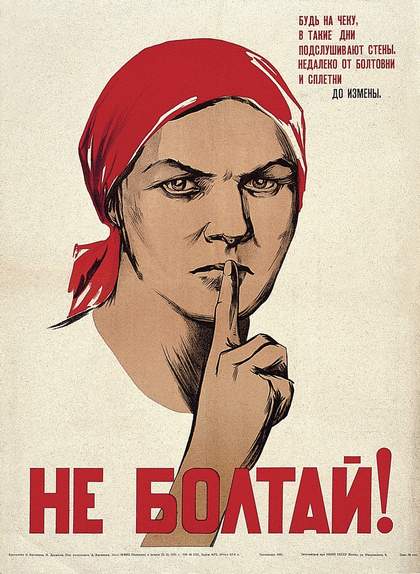

All images in Soviet times were staged and retouched, and, for Ilya, they already constituted works of art. Due to censorship, photographs were cleaned of any undesirable elements before they were printed in a magazine or newspaper. This meant that all those depicting a happy Soviet life or the incredible achievements of the Soviet system, its workers, government and the like were actually works of fiction. Ilya despised the falsity of this propaganda – for him, the system represented a void. In his albums, begun in the 1970s, he absorbed these images and added another level of fictional narrative to them, recounting invented stories of Soviet life or Soviet personages. The Ten Characters 1970–4 series of illustrated texts, for example, explores the ‘little man’ in society, each album representing, in the style of a different 20th-century art movement, the suffering and eventual disappearance – by death or liberation – of an artist-protagonist.

At some point Ilya came into the possession of a group of photographs taken by his uncle Juda (Yuri Grigorevich Blekher) – some were images of Moscow, but mostly they were everyday views of the small coastal town of Berdyansk1 on the Black Sea in south-eastern Ukraine, where he lived. A provincial photographer who took pictures of weddings and was commissioned to take portraits, Uncle Juda was precisely the proverbial ‘little man’ who featured in Ilya’s stories – an archetype who also appeared in Nikolai Gogol’s novels and was typical in the Russian empire and later Soviet society2 . He took all these official shots, but his passion was for photographing sculptural plinths, monuments and park sculptures, subjects that were colloquial and old-fashioned, favoured by the type of simple, honest men for whom life didn’t give many opportunities for excitement and adventure.

In 1987 Ilya decided to create My Mother’s Album, combining Uncle Juda’s official views of a flourishing village with his mother Bertha Urievna Solodukhina’s memoirs, which chart her poignantly tragic life – a very different reality. For Ilya, his mother represented millions of women in Soviet society who, because of war and revolution and problems in life during the supposed happy Soviet time, struggled to survive and protect their children. The juxtaposition of these images with the personal accounts of her misfortunes created unbearable tensions on each page.

Ilya Kabakov, Labyrinth (My Mother's Album) 1990, a spiralling, fifty-metre-long installation containing the life story of the artist's mother in 76 framed works

© Ilya & Emilia Kabakov, courtesy Tate Photography

Then, in 1988, Ilya created the first version of the installation Labyrinth (My Mother’s Album) – a claustrophobic, maze-like corridor with 76 framed works hung along its walls. These showed images taken by Uncle Juda alongside fragments cut from 1950s Soviet postcards and typed excerpts from his mother’s haunting memoirs. Reflecting Ilya's inability to protect his mother from poverty and homelessness, Labyrinth (My Mother’s Album) is a dialogue – a tribute by a son to his mother, but also to all women in Soviet society.

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov (born 1933 and 1945, Dnepropetrovsk) are artists living and working in Long Island, New York.