Hao Liang painting in his studio

Courtesy the artist and Vitamin Creative Space

The first impressionist artist I came to know was Monet. His best-known works are the result of painting directly from nature and his fixation with natural light certainly left a deep impression on me.

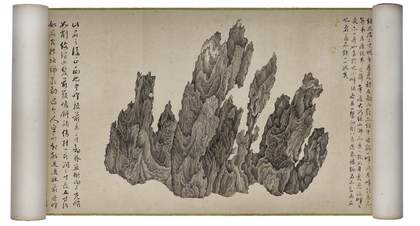

After having the opportunity to study Monet’s Houses of Parliament series, alongside the letters he wrote to his wife Alice, I was given a fresh insight into his painting practice. It reminded me of the 17th-century Chinese painter Wu Bin: the way in which he painted the scroll painting Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock for his friend and patron Mi Wanzhong was not dissimilar to how Monet created the Houses of Parliament series. They were both working with a subject from nature. Despite the different appearances of the works, and the three centuries that set them apart, it is still possible to compare the two artists’ methods and approaches.

Monet had an extraordinary fascination with the objective world. The atmosphere conjured by light and fog inspired Monet to create the Houses of Parliament series, and the ebb and flow of these external elements affected his state of mind as he worked: ‘The weather is extremely changeable, but quite splendid ... I can’t tell you what a fantastic day I’ve had. Wonderful things, but not even lasting five minutes, it’s enough to drive you mad.’ His method was rooted in the tradition of life drawing, yet none who came before him were so trapped in the maze of outward visuality. His meticulousness regarding appearance became a manifestation of his self-consciousness, opening the door to modern painting.

Three hundred years before Monet, Wu Bin, an artist from the coastal Fujian, painted the prized Lingbi rock [a type of limestone rock found deep in the red mud of the Qingshi mountains] in Mi Wanzhong’s collection, having seen it prominently displayed on his friend’s desk. From this miniature, grandeur is glimpsed.

Wu Bin, Ten Views of a Lingbi Rock (first view), 17th century

Courtesy Sylph Editions, London

Mi recorded the process of its creation in the scroll’s colophon: ‘When Master Wu Bin, famous throughout the world for having the skill of Hutou [the famous Jin dynasty painter], heard about it, he came to view it. He was so surprised that he said that it was the most astonishing sight he had seen [in] his whole life. Then lying supine before it, he wandered about in it for a month, exploring it assiduously from morning to night, his consciousness merged completely with it. Only then, taking up ancient paper, he first portrayed it straight on from the front and back, and, leaving that unfinished, continued sketching the myriad aspects of the left and right sides, leaving that unfinished too. Then he went back and in the round diagonally modelled the front and back and left and right sides together with the base from the front and the base from the back – ten aspects in all. With that, all his skill was exhausted in it. But its mysterious chimerical appearance is equal to that of the unfathomable numinous spirits that appear with the ash of lightning in the wind – just a moment later one cannot remember what they were like. Even for such an enthusiast of the strange and wonderful as Wenzhong, he could only give up before it! Ah! How can a marvel reach such degree of perfection as this!’

This work exemplifies how the craft of Chinese painting reflects the way nature is understood from the subjective world – from imagining through others' accounts and representations, to becoming one with nature – where there is no longer a distinction between the self and what is beyond.

The painting techniques of Monet and Wu Bin had little in common, yet they both presented multiple views of a single subject, and, through their different routes, both created works that disengaged from the objective world. And, looking back, did Wu Bin's time not also mark the beginning of Chinese modern art?

The EY Exhibition: Impressionists in London, French Artists in Exile (1870 – 1904) is on at Tate Britain, 2 November – 7 May 2018.

Hao Liang is an artist living and working in Beijing. Translation from Chinese by Gigi Chang. The quotation by Mi Wanzhong, translated by Richard John Lynn, is taken from Crags and Ravines Make a Marvellous View, edited by Marcus Flacks, Sylph Editions, London 2017.