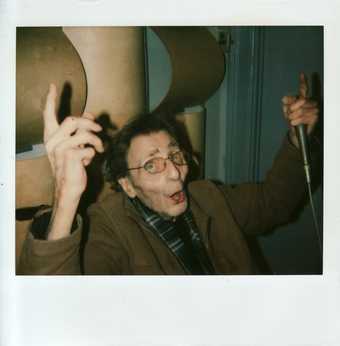

Henri Chopin performing at Radio Centraal, Antwerp on 14 December 2007

Photo © Dennis Tyfus

I spend most days in my studio. The blinds are down and I have a pencil in my hand drawing out from a piece of paper some imagined thing. There is no silence.

The pencil scrapes like a small saw, and outside lorries rumble backwards and forwards as my area is regenerated around me. For company and to mask external distractions, I listen to music, often the same piece over and over. My preferred companion above all others is Henri Chopin (1922–2008). He is called a sound artist, musician and poet. It was after the Second World War that Chopin did what he did. And how to say in words what he did when what he did was to do without words? What you can do without and still be human is what Chopin says, or sounds.

I imagine Chopin’s antecedence thus: Chopin, born 1922. Thomas Mann, born 1875. In 1947 Mann publishes Doctor Faustus. Somewhere very much in the middle of the book comes a confession of the narrator Serenus Zeitblom. He is writing the story of his friend, the brilliant composer Adrian Leverkühn, but literary conventions demand a politening of time’s passage, aphoristic paragraphs and the organising of time and events into chapters. Zeitblom despairs of these constraints and falsities, wishing for a writing that just flows, that just is as Adrian ‘is’.

Four years after Doctor Faustus, Samuel Beckett (born 1906) publishes Molloy, a book with barely a break. It is the flow Zeitblom yearned for. Molloy is. If there were a musicality to Molloy, it would be the sounds that Chopin made. What does this music sound like? It is without tune, it is the sound of just being born and just dying. It is the sobbing of a monster and the gasps of an angel. It is the miniscule movement of the smallest internal organ, and it is the storm that rasps the whole earth. It is everything and it is the void. What can I say?

Paul Noble is an artist who lives and works in London. His exhibition at Gagosian, San Francisco, opens in November.