Faith Ringgold on her painting American People Series #20: Die 1967

Courtesy the artist

At the time I made American People Series #20: Die all hell was breaking loose across parts of the United States. There were riots as people fought for their civil rights. Not much of this was being recorded in the press or on the TV news, but I saw the violence myself, and felt I had to say something about it. Artists were interpreting it – but not in a direct way. In fact, the art of that time in the 1960s was beautiful – abstractions – but it was ignoring the hell that was raging for the African American people. There was a lot of objection to art that was expressive or emotional.

During the long hot summer of 1967 I was given a space in the Spectrum Gallery in New York City to paint the large work, which was where I would have my first one-person show. There is a lot of blood in the picture, which some people found scary: one woman who came in and saw it gasped and ran downstairs because she was so terrified. It was a very emotional picture to make. Painting blood was horrible. I felt like I was bleeding when I made it.

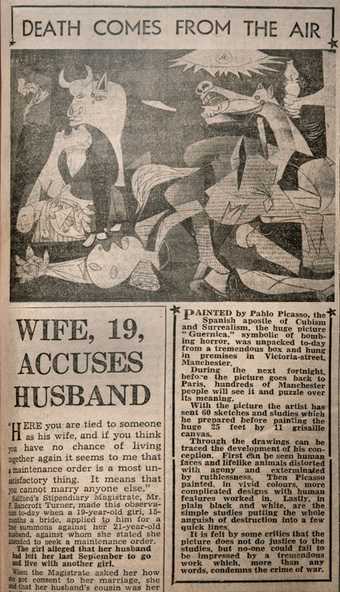

There were other sources of inspiration for the painting too. I had been going to the Museum of Modern Art with my two daughters because I wanted them to see Picasso’s Guernica, which was on loan before being returned to Spain some years after Franco died. And in terms of Die’s composition, I was inspired by Kuba textile designs (unique to the Democratic Republic of Congo), which use shapes of divided blocks. I was also imitating the pavement blocks of the New York sidewalks.

Faith Ringgold, American People Series #20: Die 1967

Museum of Modern Art, New York, © Faith Ringgold/ARS, NY and DACS, London 2017

I am very excited to see that my painting now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, like Guernica once did, some 50 years after it was made. Unfortunately, it also remains a relevant painting. It is sad to say, but history repeats itself.

Faith Ringgold lives and works in Englewood, New Jersey.

Jack Whitten recounts how meeting with artists such as Norman Lewis and Willem de Kooning shaped his path as a painter

Photo: John Berens

I was the only Black student in my class at the Cooper Union Art School in 1960. Robert Blackburn, who ran the printmaking department at Cooper Union, immediately reached out to me and said: ‘You must meet Romare Bearden.’ This was my first encounter with a known Black artist.

Romy, as everyone called him, was important because he gave me the confidence to pursue being an artist. It was Romy who insisted that I meet Norman Lewis. Norman, being an abstract painter, provided me with the mental opening I needed to decode the esoteric language of abstraction, which I knew nothing about. Romy sent me to Jacob Lawrence, who supported and signed my application for a John Hay Whitney Opportunity Fellowship.

The 1960s proved to be an extraordinary time for me: I met Romy Bearden, Norman Lewis, Jacob Lawrence, Bill Haywood Rivers, Bill de Kooning, Franz Kline, Philip Guston, the second-generation abstract expressionists, other young Black artists; all while still being a student at Cooper Union. It all contributed to who I am today. This was my foundation; a university within a university.

My older brother, Tommy, was a jazz musician and introduced me to the New York jazz scene. I always made it a point to speak with John Coltrane whenever the opportunity presented itself. One night, after asking so many questions that he became angry at me, he shouted, ‘It’s like a wave!’ Writers on Coltrane’s music used the expression ‘sheets of sound’, but Coltrane said, ‘It’s like a wave.’ The word wave stuck in my mind.

The ‘ghost’ paintings, done right after graduation from Cooper Union, were the beginning of what I called ‘planar light’. Coltrane’s wave is a direct connection to my concept of planar light, but I could not begin to build a cognitive, concrete construct until my second one-man show at Allan Stone Gallery in 1970. Those paintings were a beautiful example of process. They were done by building large silkscreens attached to a pulley from the ceiling and pressing acrylic paint directly to the canvas. They were ‘light sheets’, unstretched canvas with sewn edges tacked flat to the gallery walls.

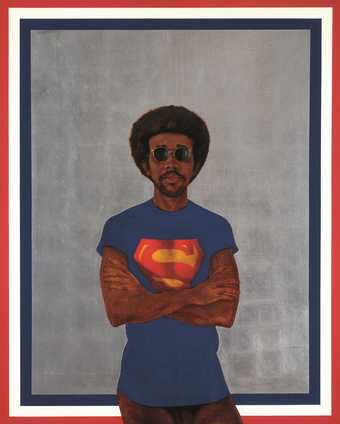

The concept of planar light became more pronounced when I discovered the ‘slab’ in 1970. The slab was a ¼ in thick layer of wet acrylic paint which was later combed through with my Afro pick. This process was designed to reveal the light beneath the surface of the slab. Homage To Malcolm was made using this process. The triangle was a symbolic form taken from Ancient Egypt.

Jack Whitten, Homage to Malcolm 1970, acrylic paint on canvas, 255.3 × 303.5 cm

© Jack Whitten, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

All the earlier Martin Luther King’s Garden series were based on gestural abstraction in full colour spectrum signifying a wide range of emotions from the joy of birth to the spectre of death. The political assassinations changed everything: Homage To Malcolm was an attempt to salvage any amount of hope remaining in our increasingly nihilistic society. It was no longer possible for me to use a full colour spectrum: there was nothing left to celebrate. Only the soul of Malcolm X was worthy of celebration.

The ‘developer’ evolved through 10 years of research from 1970 to 1980. The developer for Asa’s Palace used a strip of 3/8 in neoprene rubber attached to a 12-foot-wide 2×4 which made it into a large squeegee. The squeegee allowed me to spread great quantities of watery acrylic paint over a large surface to create a transparent layer of planar light. This process taught me that planar light could exist in a variety of densities.

Jack Whitten, Asa’s Palace 1973, acrylic paint on canvas, 273.1 × 392.4 cm

© Jack Whitten, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, photo: Christopher Burke

My 1974 solo show at the Whitney Museum was a major endorsement from an important element of power in the New York art world. It solidified my place within the dialogue of abstract painting. The establishment could no longer deny the presence of an African American abstract painter. That show proved to be a major influence on abstract painters both here and abroad.

Abstract painting is a distillation of life. Essence is produced through distillation, and essence is what gives soul meaning. Without essence there is no soul, and without soul there are no people, and without people there is no nation.

Jack Whitten is an artist who lives and works in New York City.

Lorraine O'Grady on her alter ego ‘Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’

Photo: Elia Alba, courtesy Alexander Gray Associates

In 1980 I did my first public artwork, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, for the opening of Outlaw Aesthetics at Just Above Midtown/Downtown in New York. She was a persona who wore a gown and a cape made of 180 pairs of white gloves, gave away 36 white flowers, beat herself with a white cat-o’-nine-tails and shouted poems that criticised the mindsets of the white and the black art worlds. It was a hard performance, perhaps the most difficult I’ve done. I had to strip away everything that had been instilled in me at home and at school. Mlle Bourgeoise Noire wore a crown and a sash announcing the title she’d won in Cayenne, French Guiana, the other side of nowhere. (Black bourgeoise-ness was an international condition!) Her sash read ‘Mlle Bourgeoise Noire 1955’. That had been the year her class graduated from Wellesley College. The performance was done in 1980, so it was a jubilee year – a year in which she would enact a new consciousness. Well, not entirely. At Wellesley, I’d worn white gloves myself and still had them in a drawer. But I didn’t include them in the gown. I couldn’t go that far.

After invading exhibition openings where she shouted poems against black caution in the face of an absolutely segregated art world, with punchlines such as ‘Black art must take more risks!’ and ‘Now is the time for an invasion!’, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire became a sort of impresario. She presented events such as The Black and White Show, which she curated at Kenkeleba, a black gallery in the East Village, in April–May 1983. The exhibition featured 28 artists, 14 black and 14 white, and all the work was in black-and-white. The curating and the work were subtle, but the intention was perhaps not. To a blindingly obvious situation, sometimes you make an obvious reply.

Lorraine O'Grady performing as ‘Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’ in 1980

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2017, courtesy Alexander Gray Associates

A performer holds a gilded picture frame up to the crowd as part of Lorraine O’Grady’s Art Is... performance at the African-American Day Parade in Harlem, September 1983

© ARS, NY and DACS, London 2017, courtesy Alexander Gray Associates

Another Mlle Bourgeoise Noire event was Art Is… in September 1983 in the Afro-American Day Parade in Harlem. A quarter of a century later she would convert photodocuments of the performance into an installation. When she presented these events, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire would pin her own gloves – those she’d lacked resolve enough to put into the gown – on to her chest as accessories. Perhaps she was getting stronger.

Lorraine O’Grady lives and works in New York City.

Q&A with Betye Saar

Photo: Ashley Walker, courtesy Roberts & Tilton, Los Angeles

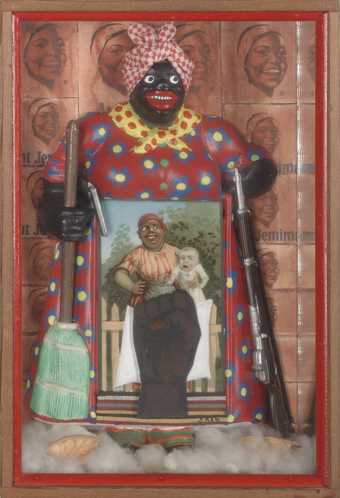

TATE ETC. One of your best-known and most controversial works, which raises many potent and continuing questions about gender and race, is The Liberation of Aunt Jemima 1972. How did it come about?

BETYE SAAR When Dr Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated in 1968, I felt such rage and helplessness. I was a mother with three young children and wasn’t able to march in protest. I chose to express my anger by creating The Liberation of Aunt Jemima.

ETC. You were part of an enclave of artists centred around the Brockman Gallery and Gallery 32 in Los Angeles. You also curated some ground-breaking exhibitions, including The Sapphire Show and Black Mirror. How important were these environments to you as an artist?

BS I remember the Brockman Gallery and Gallery 32 fondly. Very few galleries back then were interested in exhibiting Black artists – we were invisible to them – but they both offered us an opportunity. In the late 1960s the Brockman was the main art scene for Black artists. Meanwhile, Gallery 32 had mostly exhibited male artists. I proposed an exhibition of all women artists, The Sapphire Show: (You’ve Come a Long Way Baby), including Gloria Bohannon, Suzanne Jackson, Sue Irons (now Senga), Yvonne Cole Meo and Eileen Abdulrashid.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s the feminist art movement was beginning, and Womanspace [a non-profit organisation aimed at preventing domestic violence] was created. One of the founders asked me to be on the board. I then proposed an exhibition of Black women artists, Black Mirror, which was a show of art, but also featuring black lifestyle, food, music and dance. The artists included were Gloria Bohannon, Suzanne Jackson, Marie Johnson, Samella Lewis and me.

Betye Saar, Nine Mojo Secrets 1971, mixed media, 177 × 60 × 4.5 cm

© Betye Saar, courtesy Roberts & Tilton, Los Angeles, photo: Benjamin Blackwell

Betye Saar, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima 1972, mixed media, 29.8 × 20.3 × 7 cm

© Betye Saar, courtesy Roberts & Tilton, Los Angeles, photo: Benjamin Blackwell

ETC. Which artists have influenced you over the years?

BS I consider myself an object-maker. I combine objects, materials, media and ideas to invent a new object. I am attracted to other assemblage artists. My earliest influence was Joseph Cornell, when I first saw his work in 1967 at the Pasadena Museum. I knew I wanted to make art like that. Additionally, I admire Martin Puryear’s sculpture and the work of Nick Cave.

Betye Saar lives and works in Los Angeles.

Dawoud Bey reflects on the photographers who inspired him

Courtesy the artist

As a Black artist coming of age in the late 1960s/early 1970s, the discussion about a ‘Black aesthetic’ was inescapable, and artists and photographers were not exempt from that social and political conversation. One question was what the role or function of art could be in a time of profound upheaval, as the integrationist Civil Rights Movement was transitioning into the Black Power movement with its emphasis on self-empowerment and self-definition.

Fortunately, because Roy DeCarava was at the centre of the New York black photography community, the notion of a Black aesthetic that those of us under his influence came to embrace was a complex one that encompassed not only the centrality of the black subject, but also the ability to visualise that subject through a rigorous engagement with both the formal and material language of picture-making. There was nothing didactic about Roy’s work; it was clearly steeped in the history of photography, yet proposed a radical intervention into that history by describing the subjects in a way that attempted to find a material equivalent, in the photographic print, for the experience being described. It was not merely a transcription of that experience but a highly subjective and evocative interpretation of it. The main difference, for me, between DeCarava and Gordon Parks was that DeCarava operated as an artist, free of any constraining editorial hand. Parks, as a journalist, worked pretty much exclusively on assignment, whether for the Farm Security Administration or Life magazine, with his editors having the final say over how and where his images appeared. For those of us who aspired to careers as artists, DeCarava’s path was clearly the more resonant and relevant. Although, having said that, Parks was one of my earliest heroes in that as the first Black photographer for Life he made the reality of a Black photographer working in such a high profile situation tangible for many of us.

The first time I ever saw a considerable number of pictures made by Black photographers was in the Black Photographers Annual. Its influence was profound. I realised there was a community of African Americans who made photographs, often as artists, and began to seek them out. I came to know many of them well, as friends and early mentors. The annual was beautifully designed and printed, and featured the work in a way I hadn’t seen before – with a high degree of care and respect. The fact that it was produced and published by a group of Black photographers was in itself inspiring.

Linda Goode Bryant founded the Just Above Midtown Gallery in 1974. By then I had become friends with several of the artists she was showing, so I spent time there until it closed in the late 1980s. Initially exhibiting mainly abstract work by a range of Black painters, she later included conceptual work, which was not being widely shown, especially by Black artists. I had not encountered this previously, so my ideas about conceptual art practice began to be shaped. Many of these artist friends also congregated at Studio Museum in Harlem, which was important as a space where a wide range of black creative practice took place: exhibitions, music performances and poetry readings. It became the centre of my creative community.

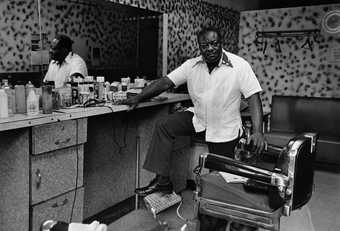

Dawoud Bey, Deas McNeil, the Barber 1976, photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

© Dawoud Bey, courtesy Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

Dawoud Bey, A Man in a Bowler Hat 1976, photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

© Dawoud Bey, courtesy Stephen Daiter Gallery, Chicago

I started working on the photographs that became Harlem, USA in 1975. In 1978, when I felt I had made good progress on the project, I approached the Studio Museum about possibly showing the work. I then spent another year in residence there completing it as a participant in the Cultural Council Foundation CETA Artist Project, with the understanding that it would be exhibited, which it duly was.

It was important to me that the first showing of those photographs be in the community in which they had been made. I wanted people who were the subjects of the work to be able to see themselves on the walls of a museum; to see it before it went out into the larger world. I thought it would be deeply meaningful if members of the community could come to the museum and see photographs of their neighbours, people who looked like them, since this very seldom happens for black people… to go into a museum and see a reflection of yourself. One of the most gratifying experiences for me, with that initial exhibition of Harlem, USA, was seeing the number of people from the community who did in fact attend the show. I wanted to make the museum space a more directly engaging one.

Dawoud Bey lives and works in Chicago.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, supported by Ford Foundation, Terra Foundation for American Art and Henry Luce Foundation, with additional support from Tate Patrons and Tate Members, Tate Modern, 12 July – 22 October. The exhibition is curated by Mark Godfrey and Zoe Whitley, with assistant curator Priyesh Mistry, and will tour to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, and the Brooklyn Museum, New York.