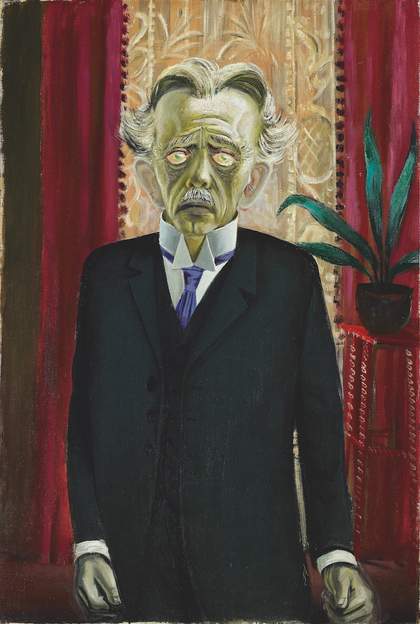

Otto Dix, Portrait of Dr. Heinrich Stadelmann 1920

© DACS 2017, image © Art Gallery of Ontario

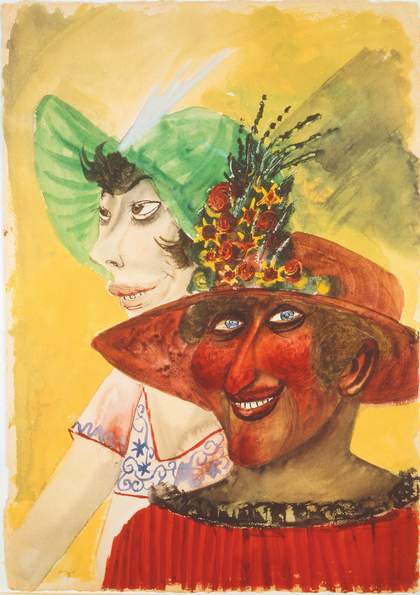

Otto Dix, Lady with Dog 1922

© DACS 2017, private collection, photo: Roman März

Otto Dix, Servant Girls on Sunday 1923

© DACS 2017, courtesy Otto Dix Stifung

Taken together, these arresting images by the artist Otto Dix (1891–1969) and the photographer August Sander (1876–1964) powerfully convey the changing nature of German society and politics from the First World War through to the Nazi era, one of the most dramatic periods of modern history.

The violence and brutality of the war was represented by Dix from personal experience without illusion or glorification, conveying the suffering of the front-line troops with enormous power and pathos. The bitterness of Germany’s defeat in 1918 was compounded by economic collapse, as hyperinflation destroyed jobs and savings, driving some to suicide (2,000 Marks in 1923 would have been worth almost nothing).

From 1919 to 1923 the new Weimar Republic, brought to power by the revolution and the enforced abdication of the Kaiser, was racked by political violence, as street fighters on the right and the left erected barricades and attempted to take control by force.

The insecurity of Weimar culture and the sense that old taboos had broken down prompted artists to turn their attention to the outcasts of society, to murderers and their victims, to prostitutes and the brothels where they worked. The urban milieu that Dix portrayed was only part of Weimar society, however, even if it was the part best remembered nowadays.

August Sander’s photographs of scenes and people in the rural world are a reminder that huge swathes of Germany had hardly anything to do with the hustle and bustle of Berlin or the grimy, smoke-polluted valleys of the industrial Ruhr. Living in a largely traditional social environment, partaking in simple pleasures such as travelling circuses, peasants and farm workers understood little of the raucous cultural life of the city, and what they did understand, they treated with resentment and disapproval.

Farmers suffered badly from an agricultural depression that continued throughout the 1920s and became markedly worse with the world economic crisis that began with the Wall Street crash in 1929. By 1932, more than a third of the German workforce, above all in industry and banking, was unemployed.

While the rural communities in Protestant areas at least turned to the rising force of the Nazis, it was mainly the middle classes who deserted their previously liberal and conservative politics to vote for Hitler in the early 1930s. The calm and seemingly untroubled bourgeois characters photographed by Sander became deeply anxious in the face of the seemingly inexorable rise of the Communist Party, which gathered the support of millions of unemployed workers and gained 100 seats in the Reichstag, the national legislature, in November 1932.

With unorganised workers, new voters and women embracing the Nazi cause as well, Hitler’s movement was the largest party by this stage, and in January 1933 he was appointed head of a coalition government whose declared policy was to overthrow the democratic institutions of the Weimar Republic.

Within six months the Nazis had eliminated all the other parties by a mixture of pseudo-legal decrees and mass storm trooper violence on the streets. All through their self-proclaimed ‘Third Reich’ opponents were arrested and incarcerated as political prisoners in Germany’s state penitentiaries. As well as Jewish and disabled people, gypsies and homosexuals became victims of persecution as the regime arrested them and put them into concentration camps. The mentally ill and hereditarily disabled were forcibly sterilised and then, during the war, put to death.

Artists such as Otto Dix, condemned for his critical representation of the violence and suffering of war, or Raoul Hausmann, a radical exponent of the dada movement in the 1920s, were denounced as ‘degenerate’. Theatre criticism was banned because with all plays now sanctioned by the regime, it would have been tantamount to criticism of the Nazis. Beggars and travelling entertainers were cleared off the streets; circuses, most of them run by Jewish families, were brought under Nazi control and purged.

The Third Reich aimed to return to Germany the territories taken away by the peace settlement of 1918–19 and then launch a war of conquest that would subjugate Europe to the Nazi yoke. Sander’s later photographs reflect the increasing militarisation of society. The Nazis conscripted millions of foreign workers to keep the munitions factories going and bring in the harvest.

With 500,000 or more civilians killed in Allied bombing raids, and over five million German soldiers killed in the fighting, a number of the people photographed by Sander or depicted by Dix were unlikely to have survived beyond the end of the war.

Richard J Evans is Regius Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Cambridge and author of The Coming of the Third Reich, published by Penguin Books.

Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919–1933, Tate Liverpool, 23 June – 15 October, comprises two exhibitions: Otto Dix: The Evil Eye, curated by Dr Susanne Meyer-Büser, Kunstammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Francesco Manacorda, Artistic Director, and Lauren Barnes, Assistant Curator, Tate Liverpool; and ARTIST ROOMS: August Sander, curated by Francesco Manacorda and Lauren Barnes, with the co-operation of ARTIST ROOMS and the German Historical Institute.