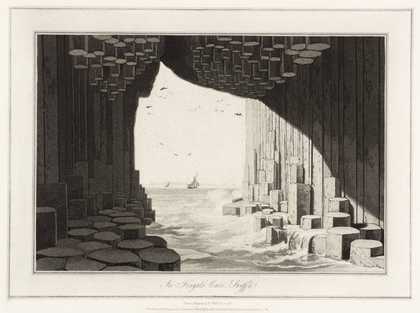

When the artist Thomas Joshua Cooper took an icy swim with his friend and fellow artist Ian McKeever into the mouth of Fingal’s Cave on the island of Staffa, he wasn’t doing it just for fun. This was, as he described it, “a pilgrimage work” that was to join him with a history of travellers to the cave, including the naturalist Joseph Banks, as well as artists William Daniell and J.M.W. Turner. For Cooper, Staffa has become as much a mental as a physical space that “remains strange and genuinely mysterious” to him.

The landscape of Britain has always been more of a touchstone for the emotions of artists than a backdrop, and one that has highlighted its awkward and ever-changing relationship with man. From James Ward’s Gordale Scar, a Sublime homage to the durability of geology over the hurried human life, to Edward Burra’s ironically titled An English Country Scene II, filled with petrol-guzzling lorries, landscape has been best defined by an artist’s personal vision. For Paul Nash, a sense of place was shaped by the invisible and the “unseen” in the land around him, while for Constable, it was some thing more palpable: “The sound of water escaping from mill-dams… willows, old rotten banks, slimy posts and brickwork… these scenes made me a painter and I am grateful.”

Jonathon Porritt on Edward Burra’s An English Country Scene II 1970

I have a friend who won’t let me describe the landscapes of the UK as natural. To him, they are all deeply unnatural, however beautiful, striking or romantic they might be. They display nature tamed and managed; nature as an instrument of our destiny as a species, but not nature as nature. I resist this Garden of Eden absolutism, for we are part of nature too, materially and constitutionally, not just in nature. But for twenty years or more, I’ve tracked those maps that identify the geographical areas where you or I could still take a walk free of juggernaut roar or pylon hum, where you or I could experience the night sky uncorrupted by our unnatural enlightenment – and the sad truth is that those areas get smaller and smaller, year by year. And as they shrink, green giving ground to the encroaching machine, then what it is that makes us truly human

Wim Wenders on John Crome’s Moonrise on the Yare c.1811–16

When I stand in front of a romantic painting – and, boy, do I love Caspar David Friedrich – I somehow never believe that the places depicted really existed. They seem to stem from an interior landscape, from something seen in a dream and then remembered on canvas.

I was amazed when I first saw Moonrise on the Yare and how much I felt transported in time, and how much I trusted the man to be taking me to the actual location. The work has an eerie quality of being contemporary. It is hard to believe it was made way before anybody ever laid their eyes on a photograph. It was painted at a “magic hour” – the privileged light that filmmakers and photographers cherish. Maybe we just feel, pretentiously, that we have some sort of insight today that a painter in the early 1900s could not have had.

Well, either John Crome anticipated how our eyes were going to be conditioned through photographs, or he just had such a deep knowledge about light that he was able to create an aura that transcended his painterly medium. I stand there transfixed, stupefied. There is a depth of belonging in this painting, of being there, body and soul, of total abandon to these places that puts our contemporary hubris in perspective. We don’t take the time anymore to be so reverential to places, we don’t give them that respect.

Siobhan Davies on Ivon Hitchens’s Divided Oak Tree No. 2 1958

Ivon Hitchens

Divided Oak Tree, No. 2 (1958)

Tate

My parents slowly collected work by British artists during the 1950s. As a child I just existed among them. My father was a gambler, and one day when I returned to the flat, there were only pale marks on the walls instead of paintings. The long rectangular mark on one wall was the saddest for me. An Ivon Hitchens painting had been there, a picture of a dark wood reflected in water. An incredible use of greens, rough paint strokes but so particular and necessary; they described a secret place. A quiet piece of mysterious country I could look at from a London flat. It represented mossy smells, shadow, light and unusual sounds. It was the first painting I knew really well.

The Reverend Alan Walker on David Cox’s A Train on a Viaduct

David Cox

A Train on a Viaduct ()

Tate

The speed of train travel was a new and frightening experience for most people. It had an almost supernatural quality to it: “FASTER than fairies, faster than witches,” wrote Robert Louis Stevenson in his From a Railway Carriage. The steam engine was an apocalyptic beast with a consuming fire in its belly, belching sparks and smoke, scattering herds and flocks on its approach, leaving a serpent’s trail of oil and vapour in its wake. The artist has kept his distance, tried to turn the train into something small and tame, nothing more threatening than a hamlet on the horizon. But now it is the viaduct that engages us. The iron road has conquered the landscape. We no longer see the hills, but what joins and defeats them. “Is then no nook of English ground secure / From rash assault?” asked Wordsworth in his Sonnet on the Projected Kendal and Windermere Railway (1844). “Plead for thy peace, thou beautiful romance / Of nature; and, if human hearts be dead, / Speak, passing winds; ye torrents, with your strong / And constant voice, protest against the wrong.” With the coming of the railway, space was annihilated by time. Distances would now be measured in hours not miles. Clocks would be reset as local time was replaced by a universal “railway” time. Cities and towns became part of a network greater than themselves. The countryside became a space that was in the way – to be cleared, amended and improved by cuttings, embankments and tunnels. The artist stands in the place of a solitary yokel observing the passing of the train, but from its windows maybe 100 pairs of eyes catch a fleeting glimpse of a passing world.

Richard Fortey on James Ward’s Gordale Scar (A View of Gordale, in the Manor of East Malham in Craven, Yorkshire, the Property of Lord Ribblesdale) c.1812–14

I know of no other painting where geology looms so massively as in Ward’s Gordale Scar. The cattle huddle beneath the cliffs, as if for protection from the gathering storm. The great gash in the rock outcrop is testimony to the power of erosion and the aeons that must elapse for the tumbling stream to carve a chasm. We recognise our own insignificance in the face of relentless natural forces. Looking closer, the beast to the right of the picture is a strong animal, the best that husbandry can provide. The painter wants us to notice this animal: caught by the glancing sun before the storm, it seems to highlight the paltriness of our trivial tinkerings with nature, compared with the sculpture of the mighty crags achieved by elements indifferent to human timescales. When all our works are banished from the earth, the limestone cliffs will endure, shaved back no more than a millimetre or two by the passage of millennia. The sombre palette permits no notions of prettiness: everything is arranged to stimulate our awe.

José Loosemore on Evelyn Dunbar’s A Land Girl and the Bail Bull 1945

In 1940 I was eighteen and in my first job as a land girl. I was assistant dairy instructress of the then County Institute at Sparsholt, near Winchester. At that time Evelyn Dunbar came into my life – a tall, willowy woman with a country-air complexion and very red cheeks. She was an official war artist who had been seconded to our staff to record the life of the land girls. Evelyn took an interest in me. She was wondrously kind and helped me to cope with being a teenager in an adult world. She painted me in uniform in the dairy. It gave her great pleasure to depict the stiff yellow oilskin aprons which the girls wore. She would get up early, around 6am, and trudge across the farm in all weathers, squat on windy hillsides, or perch precariously in all positions to obtain her records. In the evening she amused us by drawing our likenesses on the lecture room blackboard in good-humoured charaterisation. It was wonderful to have someone so interesting and inspiring to keep company with at that time.

Mark Avery on Cedric Morris’s Landscape of Shame c.1960

Sir Cedric Morris, Bt

Landscape of Shame (c.1960)

Tate

This picture of dead birds in a bleak landscape was stimulated by the painter’s anger at the impact of poisonous pesticides on birds in the 1950s and 1960s. For me, it is highly evocative of the even greater losses of wildlife from the countryside over the past three decades. It used to be commonplace to see birds such as the grey partridge (it’s there in the centre of this painting) as I walked in the countryside, but now sightings of them are rare events to be treasured and noted down. The cause of these declines has been the grinding pressure of public policy forcing farmers to remove hedges, drain wetlands and simplify far-ming systems. This painting shows a countryside which has lost all its beauty – no trees, no hedges and no wildlife. Sadly, its awful warning remains as relevant today as it was 40 years ago. Landscape of Shame should be hung in the entrance to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs to remind politicians of what we must avoid.

Michael Palin on Walter Richard Sickert’s Brighton Pierrots 1915

Despite its feeling of spontaneity, there is evidence that Sickert worked hard to get this picture right, apparently visiting the pierrots’ show every night for five weeks. The artist’s point of view, looking up at a big foreground stage, could be his way of identifying himself with the performers (he had, after all, trained to be an actor), but it also allows him to relate the stage to the half-empty audience, and to the brightly-lit blocks of Brighton’s sea-front towering in the background, emphasising the isolation of the performers. Brighton Pierrots seems to me to be a study in distraction. It’s as if all the characters have their minds on other things. I wonder if Sickert intended this sulphurous twilight sky and the inattention given to the pierrots as an image of a greater performance that was taking place 100 miles across the Channel, where young men who weren’t entertainers or audiences were fighting a huge and bloody war.

Thomas Joshua Cooper on William Daniell’s In Fingal’s Cave, Staffa, a print from A Voyage Round Great Britain 1814–25

William Daniell

In Fingal’s Cave, Staffa ()

Tate

In 1987 and 1988 I spent more than three weeks living on Staffa – a very small island an hour’s boat ride from Mull in the Inner Hebrides. The place is full of little surprises, daft ones and intimidating ones. Mechanical silence and human quiet come to be anticipated and greatly appreciated. Wind and sea sounds, bird calls and the occasional unexpected chime of a sheep bell become the familiars of this island’s speech. During my first working visit in 1987, I went with my friend, the painter Ian McKeever. He and I swam out into the mouth of Fingal’s Cave. The wind-driven choppiness of the cold sea made this short swim difficult, intense and more than a little frightful. It provided my first view of the cave. That view lingers with me still. Later, and over several further visits, I would walk the length of the cave (whenever the tide allowed) many times. For some reason I never felt comfortable or mentally at ease in the cave itself. The floor is very slippery. Seaweed and salt slime smear the basalts on the path and create a pungent tang in the air. It remains a strange and genuinely mysterious place to me. In 1988 I finished my three-part Giant’s Causeway work, emerging, submerging, emerging, which includes a component made while standing on top of Fingal’s Cave overlooking the sea towards Northern Ireland. This was a pilgrimage work, and as such it joined me with a history of travellers to the cave that included the naturalist Joseph Banks, as well as William Daniell and J.M.W. Turner.

Rick Stein on Ben Nicholson’s 1943–45 (St Ives, Cornwall) 1943–5

What is it about the quality of the light in St Ives? It must be that here is a large town right on the Atlantic Ocean. It’s not common. Padstow, where I live, is surrounded by hills, so the light is diffused by green and blue, but St Ives is all sky, sea and surf, so that the white light falls everywhere. And nowhere is this better captured than in Ben Nicholson’s painting. I’ve known it forever. Is my sense of the light from what I see or what I read into 1943–5 (St Ives, Cornwall)? I love the bleached buildings, the light quay and the black boats beyond, and because it was painted in the Second World War, there’s a union jack on the mug in the foreground – a perfect counterpoint in bright red and blue to the seaside colours behind.

David Matthews on Sidney Nolan’s Peter Grimes’s Apprentice 1977

Sidney Nolan’s painting of Peter Grimes’s drowned apprentice is a vivid evocation of Aldeburgh, where the swirling grey sea constantly threatens to overwhelm the little town, and fishermen still sell herring from their boats drawn up on the shingle beach. Nolan and Benjamin Britten felt a close sympathy as artists, in particular because of their common response to innocence and its fate in the cruel adult world. When I was an assistant to Britten in the late 1960s, one of the pieces I worked on was his cantata for boys’ voices and percussion, The Children’s Crusade, for which Nolan produced some equally haunting images of doomed children. Peter Grimes’s Apprentice retains an extraordinary, luminous presence as he literally becomes part of the undersea world of fishes and seaweed.