The work is constructed simply of two wooden boxes, easily mistakable for Minimalist sculpture. It is inscribed with its own title and instructions: “Boxes for Meaningless Work. Transfer things from one box to the next box, back and forth, back and forth, etc. Be aware that what you are doing is meaningless” (Walter de Maria, Boxes for Meaningless Work, 1961). The artist’s directions animate the object; you can almost hear the dull thud of an item being dropped into the bottom of each hollow box, generating the sad echo of something being discarded in an empty bin, or the sound of th e first item in a collection rattling to the bottom of its container. The noise becomes a rhythm as the user shuttles the item from one box to the other, over and over again, knowing that the process will serve no purpose other than to exhaust the person performing it. He will eventually have to stop, and therefore fail to complete his task. None the less, this futile process - functionless, repetitive and bound to fail – is a work of art.

The ironic contradiction is not lost on de Maria: “Meaningless work is potentially the most abstract, concrete, individual, foolish, indeterminate, exactly determined, varied, important art-action-experience one can undertake today… By meaningless work I simply mean work which does not make money or accomplish a con-ventional purpose… Filing letters in a filing cabinet could be considered meaningless work only if one were not considered a secretary, and if one scattered the file on the floor periodically so that one didn’t get any feeling of accomplishment.”

The imaginary rhythm emanating from de Maria’s boxes signals the steady beat of countless works to follow that took fruitless labour or seemingly purposeless tasks as the subject or medium of the art itself. Echoing inside these hollow vessels are the sounds of Mel Bochner methodically arranging coins on the ground to photograph them (Axiom of Indifference, 1971–3), Vito Acconci quickening his pace to follow people down the street in Following Piece 1969, or Bruce Nauman bouncing balls against the walls in Bouncing Two Balls between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms 1967–8.

As the singular, unique art object began to dematerialise in the 1960s, the possibilities for what art could be expanded infinitely to include a hole carved in a wall, the exact measurements of a room, an unrecorded dialogue, a distance travelled, a closed exhibition, or the simple act of waking up day after day. The process of meaningless work or the execution of worthless tasks became a medium, method, material and metaphor for artwork. Artists adopted systems to organise or expedite these processes, but the systems they chose were often irrational, illogical, absurd, or destined to sabotage themselves.

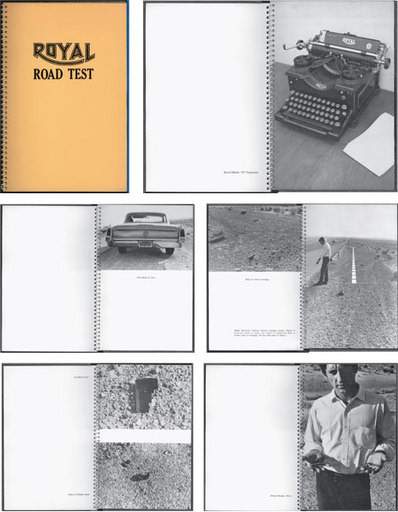

Ed Ruscha

Royal Road Test 1967

Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Institute © Ed Ruscha

Conceptual art, despite its associations with objectivity, acknowledged and mined the subjectivity and flaws of its own methods. As Sol LeWitt proclaimed in his seminal 1967 article in Artforum, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”: “Conceptual art is not necessarily logical. The logic of a piece or series of pieces is a device that is used at times only to be ruined.” Unscientific or nonsensical experiments were none the less rigorously documented. Ed Ruscha tested the effects of gravity and impact on a typewriter thrown from a speeding Buick (Royal Road Test, 1967). Lee Lozano investigated the consequences of smoking excessive amounts of marijuana in Grass Piece 1969: “Make a good score, a lid or more of excellent grass. Smoke it ‘up’ as fast as you can. Stay high all day, every day. See what happens.” Both artists recorded their findings accordingly. Douglas Huebler’s Variable Pieces constituted any activity at all, including his own attempt to photograph everyone alive (Variable Piece No. 70, 1971–97). Despite their sometimes rigid and formulaic approach and presentation, these methods were impossible to uphold. Such systems short-circuited as they succumbed to their own built-in shortfalls.

Bruce Nauman failed in a visceral, almost aggressive way, setting himself a variety of impossible tasks and sometimes getting visibly angry or frustrated if he could not complete them. In Failing to Levitate in the Studio 1966, for example, the artist documented a performance in which he attempted to levitate while lying between two chairs. According to Nauman, the attempt did not fail for lack of effort: “I was working on the exercise in the studio for a while and wanted to make a tape of it, a record, to see if you could see what was happening. When I did the things, they made me tired and I felt good when I finished, but they were not relaxing; they took a lot of energy and concentration and paying attention…”

Clearly, the difficulty of the task had no bearing on the exertion he put forth. The image of the artist – stiff as a plank, arms at his sides and toes pointed upward, intent upon achieving a feat of mental and physical concentration – is superimposed on another one of Nauman: chair pulled out from under him, legs splayed wide on the scrap-laden floor of his studio. Granted, his feet have travelled only from the top of the metal folding chair to the floor, resulting in an awkward, uncomfortable collision between his neck and the edge of the seat, but the sound of his limp body slumping to the ground implies a much harder fall. Despite his best effort, he had not succeeded in accomplishing the kind of metaphysical or transcendent feat that we expect to transpire in the artist’s studio.

As opposed to the palpable discomfort Nauman experiences, Bas Jan Ader performs his work from the comfort of a plush leather armchair in The Artist as Consumer of Extreme Comfort 1968/2003. In this photograph, the artist gazes forlornly into a dimly lit fireplace, while a lamp beside him yields a comforting yellow glow. An unattended book sits in his lap, and a glass of whiskey is propped in one hand, as his concentration drifts towards the crackling fire. At first glance, it appears that the frustrated artist is too sad to tell us that he has given up – he is out of ideas and no longer even tries to create work. When, in fact, he has forsaken art making for pure leisure. Rather than pace his studio or wander the streets in search of miraculous inspiration, he cosies himself up by the fire.

How can we reconcile this indulgent state of inertia and self-assured repose with Ader’s other seemingly desperate attempts to be noticed: his wall painting which pleads “Please don’t leave me”; his postcards dispatching the resigned message, “I’m Too Sad to Tell You” 1971; or his straightforward recording of himself tumbling head first off the roof of his house into a hedge? In most of Ader’s work, as in some of Nauman’s, failure itself is staged and systematically documented. His repeated prat falls land somewhere between theatrical melodrama and possible suicide attempts. The sound of Ader continuously splashing into the canal as he falls off his bicycle yet again would eventually foretell his last work, In Search of the Miraculous (1975), in which he was lost at sea during an attempt to cross the Atlantic in a small boat.

Taken in earnest, Ader’s and Nauman’s insistence on trying to perform physical impossibilities and then document their shortcomings, seems to have been a test of the impact of their own human and artistic failings on the world. But they attempted their feats knowing that these minor failures bore only minor consequences on the world itself. Why not set themselves a task they could deftly and triumphantly complete? Perhaps they sensed that if their systems functioned efficiently or successfully, they would be indistinguishable from “ordinary work”, and could no longer be called art.

In contemporary art, the repeated irony of failed work persists, even as Expressionism reconciles itself with Conceptualism, and the dematerialised materialises again. Failure becomes an inner monologue (or dialogue) in the work of artists such as Fischli/Weiss. With the luxury of irony and inefficiency, the pair contemplate their own self-doubt and inability to perform in Will Happiness Find Me? 2003. The installation of slide-projected images (and subsequent book) is a series of hand-scribbled questions – a potentially endless and random stream of irrational fears, doubts and postulations. Their questions are posed from the same ironic distance as Gilbert & George’s melancholic musings in To be with art is all we ask. The queries range from the banal (“Should I make myself some soup?”; “Should I remove my muffler and drive around the neighbourhood at night?”) to the existential (“Should I show more interest in the world?”; “What drives me?”; “Where will I end up today?”). As they wait for their inspiration, they transform the wait into art. But the silent undertone emerges in questions such as “Do I have to get up and go to work?” or “Should I crawl into my bed and stop producing things all the time?” – is it still okay to fail?

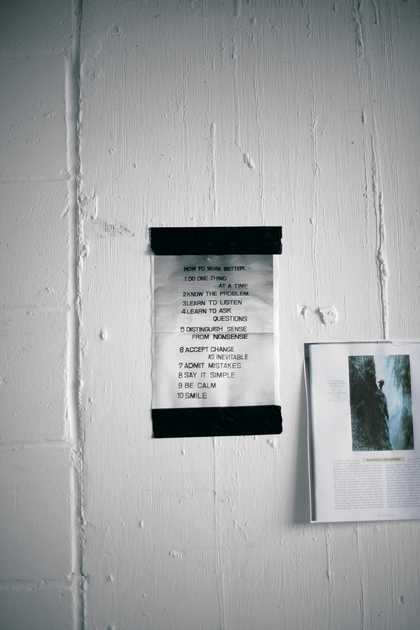

Peter Fischli and David Weiss

How to Work Better 1991

A4 Photocopy photographed by Ryan Gander

© Photograph: Ryan Gander © Peter Fischli and David Weiss

Sean Landers has carried on a similarly indulgent interior dialogue between his ego and his alter ego (the Successful Artist and the Failure) since the early 1990s. He takes the obsessive recording systems of Roman Opalka or Hanne Darboven to a personal and confessional extreme, inflecting them with what he calls the “sloppy internal”. His prolific disclosures, literally scrawled across his canvases, reflect deep self-doubt, even while they reach new levels of self-aggrandisement, leading us to question the authenticity of his admissions. Pick apart the scrambled logorrhea of Self Something 1994, and you can decipher the words: “I can’t seem to finish this painting. I am so profoundly uninspired right now I can’t tell you. I just want to eat sugary and salty snack foods and watch TV.” Sift through his abundant scribblings, and a few sentences ring out. “I am trying hard,” he writes. And it seems like he is. But a few inches away, in the same small penmanship, he notes: “There is no point to this.” Landers writes this even as he is finishing the painting. Although he makes the statement with his tongue planted firmly in his cheek, he confesses the secret of meaningless work: even frustrated art making itself can be successful artwork if it acknowledges its own failings. Better still, if it acknowledges this fact, but also acknowledges the irony of it.

Like Landers, the Swedish artist Annika Ström questions her position in the art world. In many of her works, self-doubt and insecurity reveal themselves – sometimes in a small slip of the camera, other times in bold typeface. In 16 minutes 2003 she films herself performing a half-hearted pirouette in her studio, followed by a fuzzy television recording of professional skaters making skillful loops on the ice. For Ström, this precarious performance seems to be as close to perfection as it gets, but just as near to falling down. As she points out: “The works bring up self-doubts, not necessarily about me as a person, but as a human being and her difficulties in the system in which she operates.” Her text pieces, on white paper with a hand-made coloured-in stencil, make ambivalent declarations about the works themselves, such as this work refers to no one (2004), or i have nothing to say (2004). While these matter-of-fact statements seem to refer to the wry wit of earlier conceptual text pieces, they also deny this same system of reference.

Ström acknowledges the pitfalls and frustrations of the art world she must function within. In One week bed and breakfast in Berlin for frustrated and/or uninspired, envious artist she printed application forms inviting young artists to stay with her. “Some people thought the work was cynical, but really it was about the fact that artists should stick together.” The influence of earlier works is openly conflicted, especially in the text piece this refers to all male art. “I made the piece as a comment on ‘cool guys’ referring to other ‘cool guys’ in the 1960s, as a means of giving their work credibility and getting it into public collections,” she explains. “Ninety per cent of young male artists are referring to the 1960s guys right now. If it makes sense to refer to something, and it produces a new work, then it’s fine to me. But it seems rare.” Ström’s ambivalence about art’s self-reflexivity is none the less expressed.

Jonathan Monk often makes willing and obvious use of conceptual art and its former systems, turning it into the raw material for his work and then altering it to make it decidedly new, but still recognisable. He does not just reverently refer to predecessors such as Jan Dibbets, Douglas Huebler, Lawrence Weiner, Sol LeWitt and Robert Barry, he adapts their works to change their meaning or mutate their objectivity into something humorous, absurd, personal, or aesthetic. “Sometimes people look at my work and think it’s just conceptual art with a bit of this, that and the other,” he says. “But works by conceptual artists are just a starting point for me.”

In Return to Sender 2004 Monk co-opts On Kawara’s series I Got Up 1968–79, in which Kawara sent postcards to friends and colleagues systematically reporting his whereabouts. Tearing the pages out of a catalogue that documented the work, Monk dutifully sent the pages back to the original addresses, hoping for responses, yet knowing Kawara had long left the location. “That’s something where the possibility of failure is there before you start,” says Monk. Using Kawara’s own system as a point of departure, he created another, more illogical system, resuscitating a work from the past.

Though Monk, like other artists from his generation, regularly recycles and regenerates the style and strategies of conceptual art, he concedes that these methods have aged: “As a style, conceptual art doesn’t really function anymore. At the time, they used typewriters to make pieces, because that’s what they had. But if I use a typewriter now, it’s because I want to make it look like conceptual art, and then to play with that idea.” In many of his pieces, he deals with the inevitable maturation of conceptual art to show how its rigid systems do not remain fixed, and can even fade or decay. Referring to the older works of art that he sometimes appropriates in his exhibitions, he observes: “When I see them now I’m surprised by how old they look.”

Monk pinpoints the possibilities for failure hiding underneath the surface of these older systems and brings it out by translating it into aesthetic objects. In In Search of Perfection 2003 he offers the viewer a chance to attempt to cut out a perfect circle from a piece of paper and project it on a wall to match one drawn in pencil. Most of the attempts are frustrated by the failure of the scissors to co-operate, or the viewer’s inability to imitate the artist’s perfect circle. Each viewer can experience the frustration of trying to live up to a pre-existing model or expectation for art. In 2003’s Searching for the Centre of a Sheet of Paper (White on Black/Black on White) – a reference to Douglas Huebler’s A Point Located in the Exact Center of an 81/2 x 11 Xerox paper – Monk animates two separate series of viewers’ attempts to put a dot exactly in the middle of a piece of paper (one series is a white dot on black paper, the other is the reverse). As the artist says: “The piece is done with the understanding that you can’t do it.” But his system is designed to cope with this eventuality. When it fails, the dots appear to be dancing; when it succeeds, the dots and the work itself become invisible. Success is possible, but failure is more likely. Either way, a new piece of art is made.

What contemporary artists such as Ström, Landers and Monk tap into is not the cold rationalism of conceptual artworks, but the cracks in their objective systems, or the vague, fleeting appearance of insecurity or doubt. Combined with their own conflicts about the system of the art world, what they allow us to see is not the patent successes of previous works, but their occasional futility and failure. While some conceptual art is rigorous and methodical, intellectual and distanced, it can also be paradoxical or daft, emotional or romantic. There is something fragile and fallible about taking on a project that can’t be finished, performing an act that can’t succeed, or creating a work that will never be seen. It is the repeated, unsure attempts and predictable small failures that constitute the self-effacing and endearing quality of meaningless work.

Could it be this duality that defines the most successful and enduring works? Why do artists’ flawed systems and small failures attract us? Are they more authentic, more honest, more empathetic? Perhaps it is because the work that adopts this strategy is always only an attempt, always incomplete, and must therefore admit its own shortcomings. Or perhaps it gives us hope that productivity and even success are firmly implanted at the pit of failure. Or maybe it’s the reassurance that human error can be performed without consequence or catastrophe, especially when tested in a safe environment. Art is not work precisely because it doesn’t have to “work”. The act of failure or the failed act of art making is promising and productive. Or maybe it is because when systems try and fail to create order, or break down and fail, it evokes our own failings. As Annika Ström suggests: “I guess it’s more interesting because it creates questions instead of just answering a question, a question only made by the artist… and it shows that the artist is fragile. It presents the fragile parts of us all.”