In 1896 the American artist Abbott H. Thayer (1849–1921) published an article entitled ‘The Law Which Underlies Protective Coloration’, in which he explored how animals protected themselves by the use of graduated colours and tones on their feathers, scales or fur, allowing them to be camouflaged by their surroundings. Using a language that mixed art and optics, he said ‘the spectator seems to see right through the space really occupied by an opaque animal’. While Thayer was not the first to observe how animals used this defensive colouration, he believed nature was acting as an artist, using colour and light for optical effect, and thought that this study ‘belongs to the realm of pictorial art and can be only interpreted by painters’.

It was quite a claim and, unsurprisingly, not everyone agreed, including the former President and amateur naturalist Theodore Roosevelt, who attacked the theory in his own writings. Undeterred, Thayer believed that his ideas were not only radical and visionary, but also had practical uses. In the late 1890s, during the Spanish-American war, he tried (and failed) to persuade the US government that its naval forces could benefit from ship camouflage.

Fabio Rieti

Émile Aillaud’s Tours Aillaud, Paris, painted in disruptive patterns c.1977

Photo: François Scali © Courtesy DPM

While Thayer was considered to be the father of camouflage, it was other artists who independently put such ideas into practice. The first section de camouflage in military history was established in 1915 by the Frenchman Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola, an academic painter who was serving as an infantryman. He had admired Picasso’s shard-like, geometric Cubist forms. (Picasso had also been thinking about camouflage when living in Paris during the war, and had recommended a similar strategy as Thayer in suggesting a replacement for the French field service uniform, telling Jean Cocteau, no doubt with the tip of his tongue in his cheek, that the army would better ‘dazzle’ its men if it dressed them in harlequin costumes.)

Comparable units, made up of fine artists, designers and architects, were used by the British and Americans, and, to a lesser extent, by the Germans, Italians and Russians. In fact, hundreds of artists served during both world wars, including Jacques Villon, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Franz Marc, Oskar Schlemmer, Edward Wadsworth, Arshile Gorky, László Moholy-Nagy and Ellsworth Kelly.

Among the earliest and most important British practitioners was Lieutenant Commander Norman Wilkinson, a marine painter who, in April 1917, devised a concept for the camouflage of ships called ‘dazzle painting’, in response to the number of vessels being torpedoed in the Atlantic. As he explained to the Admiralty, there was no point attempting to blend them in with the sky and the ocean, because both were so visually inconstant. Rather than aiming for invisibility, the idea was to confuse the gunner on a German U-boat as to the target’s course, size, speed or direction, using a disrupted pattern painted on to the side of the ship. A team of eighteen artists was soon set up as the Dazzle Section and installed in studios at the Royal Academy of Arts. Designs were applied to models, which were then viewed on a rotating turntable through a periscope. Those deemed worthy were sent off for implementation to various dazzle officers, including the Vorticist painter Edward Wadsworth, who oversaw operations in Bristol and Liverpool. Within a year, 4,000 merchant ships and 400 navy vessels were painted with varying styles of stripes, blocks and disrupted lines. Each had a different design, which was changed on a regular basis.

While these designs had the practical effect of saving lives, the eye-catching image of dazzle was rapidly absorbed into popular culture. Ladies’ swimwear with dazzle patterns appeared, while the composer Gordon Frederic Norton penned a ditty to U-boat officers:

Captain Schmidt at the periscope

You need not fall and faint,

For it’s not the vision of drug or dope,

But only the dazzle-paint.

And you’re done, you’re done, my pretty Hun.

You’re done in the big blue eye,

By painter-men with a sense of fun,

And their work has just gone by.

Cheero!

A convoy safely by.

The word camouflage soon entered common terminology, appearing for the first time in English on 25 May 1917 in the London Daily News, when it was used in a sentence that said: ‘The act of hiding anything from your enemy is termed “camouflage”.’ A few months later, the King of England was reported as having ‘paid a visit to what is called a camouflage factory’, where he was introduced to ‘all the latest Protean tricks for concealing or, as we all say now, ‘camouflaging” guns, snipers, observers’. By the end of the First World War, the word had been used by the English-speaking public in such a variety of non-military contexts that it had, according to The Athenaeum magazine, ‘met with more wear and tear in a few months than many receive in a century’. During the same time, there were printed references to a ‘camouflaged autocracy’, to eggs camouflaged in a scramble, and even to a telephone as having been camouflaged by its design. ‘Instead of saying “He is a bluff”,’ wrote a journalist in 1917, ‘we say “He is nothing but camouflage”.’

From cookery books to comic strips, the concept of camouflage became part of the everyday. In 1927 Louis Weinberg introduced ‘Camouflage in Dress Design’ that featured ‘horizontal parallelism, broad shoulders, wide collars and all over pattern, [to] emphasise width’, while ‘vertical parallelism offsets heaviness and creates illusion of greater length’. Fashion, glamour and military ideas neatly came together with the appearance of Chili Williams in Life magazine on 10 April 1944. She had become the number-one American pin-up girl and was subsequently enlisted by engineers at the US camouflage section at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, as their chief visual aid, so that ‘vital principles are impressed in the minds of camouflage students in a most effective manner’. Copies of her photographs were given to the best students.

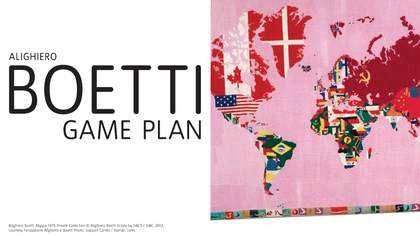

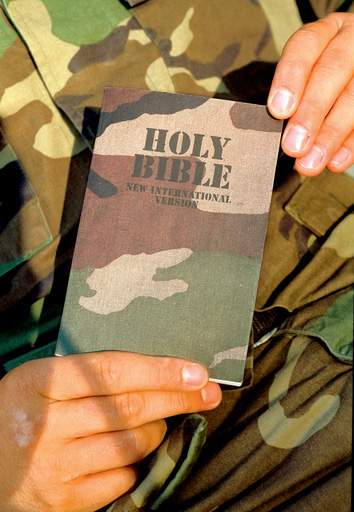

The Bible in the US woodland camouflage pattern, first introduced in 1989

Photo: Nicholas Pencelle © Courtesy DPM

The British had more mundane methods. In 1940 the War Office established the Camouflage Development and Training Centre, where it recruited a mixture of talents, including the popular stage magician Jasper Maskelyne, renowned zoologist Hugh B. Cott and the Surrealist artist Roland Penrose. They were responsible for such innovations as pillboxes disguised as ice cream parlours. Penrose, who served as a civilian instructor and wrote a guide-book called the Home Guard Manual of Camouflage, was a camouflage aficionado. As well as painting his own car in a disruptive pattern, on one occasion he experimented with a matt green camouflage cream, smeared on the naked body of his lover and future wife, the American model and photographer Lee Miller. She lay on the grass of a friend’s garden, delicately covered in netting taken from the raspberry patch. Penrose was delighted with the results, and concluded ‘that if you could hide such eye-catching attractions as hers from the invading Hun, smaller and less seductive areas of skin would stand an even better chance of becoming invisible’. Since then the practice of camouflage has provided an unlimited source of fascination for the public. From the beginnings of its application, different features have been used, frequently and repeatedly, in all corners of culture. In fashion, we have seen Maharishi’s ‘Bamdazzle’ Wilk shirt, influenced by Norman Wilkinson’s dazzle designs. In architecture, French architect Émile Aillaud’s Tours Aillaud were painted in disruptive patterns to blend into the surroundings, while Foreign Office’s Virtual House for Franz Schneider Brakel used a disruptive pattern for the main façade. Orchestral Manouevres in the Dark’s 1983 album Dazzle Ships also borrowed from Wilkinson for its title and cover design. In children’s toys, DPM’s Identifier range featured designs from Andy Warhol’s 1986 Camouflage series, and in 1999 the Boot Camp Barbie doll was launched, complete with camouflaged hair and uniform. The latter was marketed as being more cultural tool than girlie doll; the accompanying package included a lesson for girls to ‘study the history of our country and take pride in America’. Artists too have continued to draw on the history of camouflage in their work. Alighiero e Boetti’s Mimetico 1966 was made from a roll of camouflage fabric of a pattern introduced by the Italian army in 1929 and found by Boetti in a Turin flea market, Alain Jacquet produced Camouflage Hot Dog Lichtenstein in 1998 and Andy Warhol’s Self-Portrait 1986 appropriated its design from the United States army ‘woodland’ pattern introduced in 1981.

Camouflage has now become an integral part of visual culture. While its street use – graffiti, skateboard designs, et al – would suggest that it is merely a nice design, it is worth remembering its heritage and its continuing cultural significance. When Thayer initially proposed the link between art and camouflage, he was not wrong. You could say they are twins. Or, in the words of Hugh B. Cott: ‘The one makes something unreal recognisable: the other makes something real unrecognisable.’