One of Giovanni Paolo Castelli’s anthropomorphic still-life paintings of the seasons

Colnaghi

When Alberto Giacometti hand-sculpted his plaster figures with his nicotine stained fingertips he was perpetually wrestling against his own potential failure to transform and reduce his mind’s eye into palpable form. It is a struggle that artists have grappled since being able to grasp a tool, yet the innumerable variations in the artist’s approach to the human form remains a constant.

It was a strong theme running through the works on view at TEFAF, seen most conspicuously in a trans-historical exhibition called La Grande Horizontale, displayed like a mis-en-scene within the fair. Curated by former Tate director Penelope Curtis it explored the recumbent figure through the centuries. Among the works were Thomas Schutte’s intimate, table top bronze sculptures of naked women.

Thomas Schutte’s Frau V 2016

Conrad Fischer Galerie

Just as Giacometti worked with both plaster and bronze, Schutte has worked with ceramic ‘sketches’ exploring the female body, which he has then transformed into bronze figures set on steel podiums. Yet, while Giacometti’s approach was immersed in an inner struggle, rooted in the precise and transformed by the visionary, Schutte’s sculptures, while similarly monumental in intent, were underpinned with a sense of humour. A sign of the age within which they were made perhaps?

Schutte’s Frau figures offered unspoken and playful conversations with fellow artworks in the exhibition – from a 3rd century BC Etruscan funerary figure, to a reclining figure of the Virgin of the Nativity from the late 14th century, to Sadie Murdoch’s photographic celebrations of modernist Charlotte Perriand.

Pedro de Mena y Medrano’s St Francis of Assisi 17th century

Colnaghi

Yet, as the TEFAF fair showed, it is often the ancient Christian stories of pain, suffering and devotion that have propelled Western artists to explore with the greatest potency this fascination for the fragility of the human body, as seen in the carved wooden depiction of St Francis of Assisi looking humbly at the model of a crucified Christ that he holds in his hand, by Granada-born Pedro de Mena y Medrano.

Here, objects that were once considered devotional objects, more often than not residing in churches, have become venerated (and pricy) works of art thanks to the double effect of both art historical research and the art market.

Marcel Broodthaers’ Two Marilyns 1964–5

Keitelman Gallery

But secular times call for secular approaches. More recent artists have responded to the speed of cultural and social change not just through ideas of repetition and seriality but also by exploring the fragmentation of the body. A good example is Marcel Broodthaers’ Two Marilyns 1964–5, in which all we can see in his carousel of Marilyn’s face is her iconic lips.

But perhaps the most evocative and emotionally resonant ways that artists over the centuries have explored the human body is how they have expressed the face. Bodies can show us the tricks of an artist’s vocabulary – be it with a mannerist, expressionist or even minimalist twist (for the latter, think of Carl Andre’s neatly ordered stack of bricks Equivalent VII inspired by the rippling water that could see in front of him while paddling in a canoe) – but a portrait has to deliver the complexities of human behaviour through the artist’s technique.

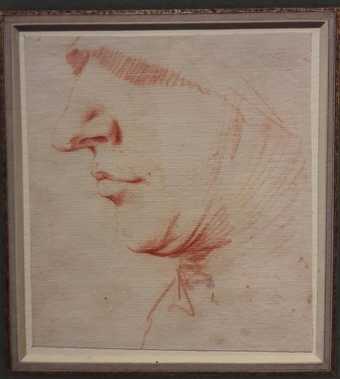

Jusepe de Ribera’s Head in Profile Wearing a Veil and a Wimple 17th century

Jean-Luc Baroni

Parmigianino’s Profile Head Study of a Man wearing a Mask 16th century

Jean-Luc Baroni

Faces are most powerful when they are unknown and anonymous, as in Jusepe de Ribera’s enigmatic fragment Head in Profile Wearing a Veil and a Wimple or Parmigianino’s early 16th century drawing of a grotesque head, Profile Head Study of a Man wearing a Mask. Yet the works that can carry the greatest weight across the centuries are often the simplest.

The exquisitely rendered 12th century French carved head of a woman, possibly from a reliquary bust, shows a face that is unadorned and humble. She has neat lines of hair, with a centre parting. Her gaze is neutral and seemingly unemotional. Yet this tender portrayal bears the intimacy of a face that you might know – like the photograph of a friend. Proof perhaps, that even after several thousand years, we are far closer to our ancestors than we might think.