Merce Cunningham Dance Company world tour, Cologne, 1964: (in helicopter) Carolyn Brown, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Doris Stockhausen, David Tudor and Karlheinz Stockhausen; (below) Steve Paxton, Michael von Biel and Robert Rauschenberg

Photograph Collection, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, New York

‘We have just so many parts and just so much time. We should extend them all,’ wrote Robert Rauschenberg. Revered for going against the dominant trend of abstract expressionism when he began his career and for being ahead of the curve of those who produced assemblage, found art and so-called junk art, rauschenberg lived up to his own desire to extend the parameters of art. In the 1950s, when many other artists in New York were content to ride the wave that had been initiated a decade or so earlier, producing work that foregrounded painting technique and emphasised a metaphysical outlook, he, along with a handful of others, was making art that was almost anti-technique in its embrace of found materials and imagery, highlighting the daily reality and commonality of urban dwellers.

Even the term neo-dada, sometimes applied to his early work, does not do justice to Rauschenberg’s attempts to distance himself from traditional art-making practices and goals. The dadaists had, indeed, used non-art media and approaches, and more recently Jean Dubuffet had employed mundane materials. Maybe it makes sense to look elsewhere for rauschenberg’s signal innovation; in particular, to the artist himself. In the way he presented himself, his hair and clothing styles, his ever-ready smile in photographs, in his eagerness to collaborate, to subsume himself into collective art-making complexes, he reveals himself to be one of his greatest works. He famously stated that his work took place in the gap between art and life – by pushing it into areas considered not applicable to artistic production, he emphasised the social relations that surround art-making.

Rauschenberg’s abiding interests in dance, as well as in building stage sets and making costumes, began in his youth. As a child and throughout his early years, he was attracted to theatre and displays, often earning money through his designs and creations. At 13 he considered becoming a minister, but changed his mind when he discovered his parents’ religion forbade dancing. He began his art studies at the Kansas City Art Institute and School of Design, remaining there for most of 1947. Working part-time, he earned enough money to go to Paris, where, with the help of the GI Bill, he entered the Académie Julian. There he met Susan Weil, who became his close companion. They subsequently married and had a son, Christopher. After returning to the States in 1948, both decided to enrol at Black Mountain College for the autumn semester, excited by an article in Time magazine on the rigorous teaching methods employed there by Josef Albers.

Albers’s emphasis on students discovering the unexpected qualities of materials rubbed off, though his teaching manner could be harsh. As Weil put it: ‘Everybody ended up in tears at least once a semester, including the most talented and favoured students.’ Her husband went further: ‘[He] was a beautiful teacher and an impossible person. He wasn’t easy to talk to, and I found his criticism so excruciating and so devastating that I never asked for it. Years later, though, I’m still learning what he taught me, because what he taught had to do with the entire visual world… The focus was always on your personal sense of looking.’

But it was not only the curriculum or teaching itself that proved useful for Rauschenberg. Elements in the air were just as important. As many who studied and taught at Black Mountain have noted, it was adept at providing an environment conducive to experimentation and collaboration, to working outside historical parameters. It was there that he found his first group of close colleagues and collaborators. He returned with Cy Twombly in the summer of 1951, making a series of completely white paintings, which John Cage credited with giving him the courage to compose 4’33”. Rauschenberg also began his Night Blooming paintings, which took an opposite tack. In them, he used black oil paint, mixing in pebbles, asphalt and other materials outside the art-making lexicon. A particularly telling photograph from Black Mountain shows him working on a mardi gras costume in the form of a unicorn, revealing connections between his earlier and later interests in dance and theatre. The unicorn also prefigures the use of animals in his art, in his Combines and beyond.

Robert Rauschenberg designing a mardi gras costume for his sister Janet, modelled by fellow student Inga Lauterstein, Black Mountain College, North Carolina, c1949, photographed by Trude Guermonprez

Photo: Trude Guermonprez. Photograph Collection, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, New York

It was 1952, though, which can be said to have provided a seminal moment for the artist. One day that summer at Black Mountain Cage decided to mount a multimedia performance, later titled Theater Piece #1. Merce Cunningham improvised a dance, poet Charles Olson read, as did poet and translator MC Richards, while Rauschenberg played Edith Piaf records on a manual-crank Edison record player, his all-white paintings suspended above the audience. This became known as ‘the first happening’, as it set the mode and standards for those to come in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The following summer, despite practically non-existent funding, Cunningham felt emboldened to found his dance company at Black Mountain.

Beginning in 1954, while showing successfully and making some sales of experimental photograms done with Weil, his White Paintings and his now-classic Combine works, which collaged large-scale three-dimensional objects on to painted two-dimensional surfaces, Rauschenberg was simultaneously deeply involved in collaborations with Cunningham and Cage. ‘I felt more at home with the discipline and the dedication of those dancers than I did in painting,’ he said, referring to his work as primary set and costume and lighting designer for the Cunningham company. ‘The idea of having your own body and its activity be the material – that was really tempting.’

Collaboration is hardly ever all plain sailing, however. After 10 years of successes, in the midst of a world tour in 1964, Rauschenberg made a statement that was one too far when he said that ‘the Merce Cunningham Dance Company is my biggest canvas’. Even though he was being metaphorical, it is also clear that this was not a diplomatic moment. It would be another 13 years before he and Cunningham would work together again.

Rauschenberg performing Elgin Tie during Five New York Evenings at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, 13 September 1964, photographed by Stig T Karlsson

Photo: Stig T Karlsson/Moderna Museet, Stockholm

The artist found other happy and willing collaborators and seems to have thrived on the energy of unpredictability and excitement that collaboration brings. He first appeared on stage in 1961, in Paris, and it is important to note the international context in which many of his collaborative works took place. By joining forces with artists from different cultures, he was opening himself up to different ways of thinking and working. Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely had a more European approach than that of Cunningham and Cage, tapping into the tradition of dada absurdist theatre and creating machines that self-destructed and mock-epic pieces such as The Construction of Boston 1962. Cage in particular was basing his methods on his studies of Zen Buddhism, enabling a mindset quite different from that in the Western theatrical tradition in terms of its expectations of time and dramatic content.

The Paris piece, which became known as Homage to David Tudor, was a multimedia extravaganza not unlike Black Mountain’s Theater Piece #1, but it presaged Rauschenberg’s branching out from his familiar group of collaborators. Tinguely had created a mechanical figure that shed metal pieces, French sculptor and painter Niki de Saint Phalle executed one of her ‘shooting paintings’, pianist David Tudor played a cage composition, Jasper Johns provided Tudor with a target made of flowers and rauschenberg painted the Combine later titled First Time Painting in real time.

Robert Rauschenberg, First Time Painting 1961, Combine with oil, paper, fabric, sailcloth, plastic exhaust cap, alarm clock, sheet metal, adhesive tape, metal springs, wire and string on canvas, 194.9 x 130.2 x 22.5 cm

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie, Stiftung Sammlung Marx, © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

While continuing to work with the Tinguely group, back in New York Rauschenberg began to frequent the Judson Memorial Church on Washington Square Park, where some Cunningham dancers and others interested in pushing the idea of the art form as far as possible into non-dance areas would gather to discuss and create performances. Those involved included Steve Paxton, Deborah Hay, Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Simone Forti and Yvonne Rainer. Many of Rauschenberg’s most significant contributions in years to come involved work created with members of this group, and in some ways his association with them put him into a more contemporary context than with Cage and Cunningham. As Hay stated: ‘Cunningham said anyone can dance and all movement is dance, but didn’t practise it. We were out to make Merce eat his words… [Rauschenberg’s] greatest contribution to the performance art world at that time was that he showed us how to play.’

Part of play is impulsiveness, the leaving behind of known practices. For Rauschenberg, that meant jumping into choreography by dint of a typo in a programme. In 1963 he was mistakenly listed as choreographer rather than stage manager for Judson performers at a pop art festival in Washington. He decided to give the error real value by choreographing a performance, and as this was to take place in a roller-skating rink, he again used that chance element as a basic compositional tool. He learned to roller skate and skated around the area with the Swedish painter per Olof Ultvedt, both wearing open parachutes. Their zooming non-traditional movement was in counterpoint to a dance en pointe by Carolyn Brown that drew on classical ballet vocabulary. This stunning choreographic debut was the piece Pelican.

Rauschenberg performing Pelican 1963 with Carolyn Brown and Alex Hay. Contact sheet #22 of Elisabeth Novick’s photographs from the First New York Theater Rally, former CBS studio, Broadway and 81st Street, May 1965

© Elisabeth Loewenstein Novick. Photograph Collection, Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, New York

Meanwhile, Rauschenberg’s career as a painter and creator of three-dimensional artworks was exploding. In 1963 he had a retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York, and his work was included in exhibitions at the Guggenheim Museum and Washington Gallery of Modern Art. By 1964 he had won the international grand prize in painting at the Venice Biennale. Some artists might have been tempted to stick to the museum-friendly, saleable work, leaving performance behind. Rauschenberg had other ideas.

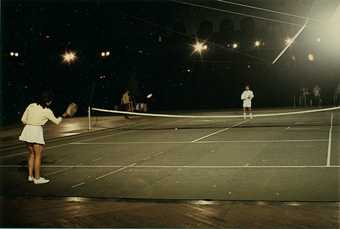

While continuing to expand his repertoire as a performer and collaborator in the 1960s, he became fascinated by new developments in technology. He had already worked with primitive machines with Tinguely; now he wanted to be part of the cutting-edge of sound, lighting and motion technologies. In 1966, after 10 months of preparation by 10 artists – Cage, Childs, Öyvind Fahlström, Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Paxton, Rainer, Rauschenberg, Tudor and Robert Whitman – and 30 engineers from Bell Laboratories, headed by Billy Klüver, the series 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering opened at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue, New York. Rauschenberg’s piece, Open Score, involved two tennis players (Mimi Kanarek and Frank Stella) with customised rackets containing sensors that triggered loud bonging sounds when the ball hit the strings, at which point one of 36 ceiling lights would turn off. When the place was in complete darkness, the second half ensued, in which a group of 500 people came in and performed a series of actions following instructions prepared by Rauschenberg. They were filmed by infra-red cameras that had been set up on the balcony and projected on large screens for the audience, who could not see them otherwise. Rauschenberg wrote, as part of his description of Open Score: ‘the conflict of not being able to see an event that is taking place right in front of one except through a reproduction is the sort of double exposure of action.’

Mimi Kanarek and Frank Stella performing Rauschenberg’s Open Score as part of EAT’s 9 Evenings: Theater and Engineering at the 69th Regiment Armory, New York, 13–23 October 1966

Courtesy Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.)

After 9 Evenings, Rauschenberg and Klüver, along with Whitman and engineer Fred Waldhauer, formed the organisation Experiments in Art and Technology (EAT) in order to further this kind of collaboration. Eventually EAT raised $100,000, teamed up with the AFL-CIO labour union organisation, and by 1969 was matching up artists and engineers from a pool of 3,000 each.

In 1962, at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Rauschenberg participated in a group exhibition of experimental technology work entitled Dynamic Labyrinth, or Dylaby. Although there was a feeling of camaraderie among the participants, some of whom – Tinguely, de Saint Phalle, Ultvedt – he had collaborated with before, Rauschenberg was disappointed that all the artists did not work on one piece together. He was always keen to minimise the emphasis on individual creativity or the idea of genius and spread the creative authority among a group of people.

Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver working on Oracle 1962–5 in Rauschenberg’s Broadway studio, New York, 1965

Photo: Larry Morris/NYT/Redux/eyevine

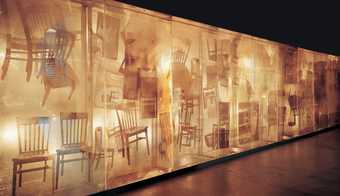

Robert Rauschenberg, Soundings 1968, mirrored plexiglas and silkscreen ink on plexiglas with concealed electric lights and electronic components, 243.8 x 1097.3 x 137.2 cm

Museum Ludwig, Cologne, © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Rauschenberg viewing a prototype for his piece Mud Muse 1970 with engineers from Teledyne and LACMA curators Maurice Tuchman and Gail Scott

Courtesy the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Rauschenberg continued to experiment, using technology to transform further the role of the artist in the outcome of the work. His first collaboration with EAT, and engineers Klüver, Waldhauer, LJ Robinson, Cecil Coker, Per Biorn and Ralph Flynn, was Soundings 1968, included in his exhibition at the Stedelijk. The imagery – photographs of chairs – was provided by the artist, but the presentation and variations of that imagery were determined by the actions of viewers. Nine plexiglas panels were joined to form a panel 8 x 36 ft. In silence it looked like a gigantic mirror in a gym, but it was sensitive to sound. Whenever a viewer talked or made a noise, the piece would respond by revealing different aspects of the imagery.

Klüver has written about their collaborations: ‘[Rauschenberg] has always seen his work as an active participant in its own environment, and the viewer as an active participant in the work.’ From the early White Paintings, which the artist saw as registers of activity in the room, to the combines, in which he attempted to bring the room, and the outside world, into the work, he was attempting to move beyond the traditional conception of a work of art. ‘I’ve always felt a little strange about the fixedness of painting,’ he once stated. It was logical, then, that he would want to tap into the possibilities of technology in the 1960s, the decade in which man was first able to walk on the moon. His interactive pieces were hits with the public, although critical response was not always so warm.

Rauschenberg working on his portrayal of the Discovery space shuttle, near the Cape Canaveral launchpad, Florida, August 1984, photographed by Theo Westenberger

Photo: Theo Westenberger Archives, 1974-2008, Autry Museum, Los Angeles

Rauschenberg’s extensive printmaking career can also be seen in the light of collaboration. Here, too, he was wont to push a traditional form, such as lithography, into unexpected areas. One of his most innovative print projects was created after he went to live on Captiva Island, Florida, in 1970, and became interested in the mundane form of the ubiquitous cardboard box. Working with the Graphicstudio press in his Tampa Clay series, he made ceramics based on cardboard originals, with tape and silkscreened details that confound the eye in their verisimilitude.

Rauschenberg’s studio was really an atelier in the classic sense that he liked to have people around during the act of creation, and photographs demonstrate his joy in his social relationships, which were often work-related. as he put it in one of his One-liners: ‘I was never able to convince people that I was more interested in us than I am in art.’ The evidence shows that he was at his happiest when he was working with others, and the border between life and art disappeared.