Bhupen Khakhar in Sayaji Baug gardens, Vadodara, 1983, photo by Jyoti Bhatt

© Jyoti Bhatt

Shanay Jhaveri When did you meet Bhupen Khakhar for the first time?

Howard Hodgkin It was at the first Triennale-India in New Delhi in 1968. During my visit I went to see the art critic and curator Geeta Kapur, who I knew slightly. She asked me what I thought of the exhibition. I told her I thought it was all rubbish – except for three pictures. She said: ‘That’s very interesting, the painter who did them is standing right here.’ That was how I met Bhupen.

SJ What was it about his pictures that struck you?

HH I felt they were the only ones there that were original. They had their own identity. They were three narrative pictures. Their authenticity shone out like a sound of a bell in this terrible, crowded exhibition.

SJ And that meeting initiated a lifelong friendship between you…

HH Oh yes, it did.

SJ I know that his trips to England in 1976 and, in particular, 1979, when he stayed with you, were very important for him personally. He said after that second visit he could appreciate how people – how men – could relate and live together. I think the experience of being in England was quite significant for him in that sense.

HH I’m sure it was. I’m amazed by what you’ve just said, because I hadn’t come out as homosexual. I thought Bhupen was gay, but I was not at all sure about that.

SJ At the time you were living with your wife and children in Wiltshire.

HH Yes, indeed, and he liked the family scene very much.

SJ He was always a very social person; he had numerous friends and liked to surround himself with people of all different types, from different strata of society. Did you spend time with him at his home in Baroda?

HH A little, in the beginning. I remember I was very impressed by seeing underwear hanging on the wall, like a picture, on a little wire coat hanger. It belonged to a boyfriend and was made of black silk. I couldn’t understand why… but it made me look at him with new interest.

SJ I know that Geeta Kapur played quite a crucial role in helping Bhupen to get his first exhibition at Anthony Stokes’s gallery in London.

HH Yes, that’s true. I was jealous, because I couldn’t get an exhibition anywhere at that time. I got Bhupen a job teaching at the Bath Academy of Art, which was a very distinguished local residential art school. There were already many artists, such as William Scott, Peter Lanyon, Jack Smith, Kenneth Armitage and Gillian Ayres, teaching there. I think Bhupen liked that.

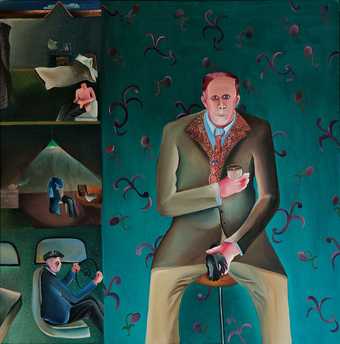

Bhupen Khakhar, Man in Pub 1979, oil on canvas, 122 x 122 cm

© Estate of Bhupen Khakhar, photo Murray Russell-Langton

SJ Did he tell you much about his impressions of England at that time?

HH He hated the cold weather. He never said anything about men living with other men, but he did say he was painting an enormous picture with portraits of everybody he’d ever slept with. I was very impressed by that. He asked me, ‘Would you do the same?’ and I said, ‘Well, my picture would be much smaller than yours.’ I’d only just begun to accept that I was gay.

SJ How do you think people in the UK reacted to his work when he first showed here? David Hockney’s pictures get mentioned when they look at Bhupen’s, but I think there is quite a difference between them – in the way they represent bodies.

HH An enormous difference; I think it’s the homosexuality in David’s pictures that makes a link.

SJ Bhupen’s pictures are more fragile. They are about embrace and touch. They’re not about physical beauty, in the same way as Hockney’s, I feel.

HH Yes, I think that’s very good…

Bhupen Khakhar, Grey Blanket 1998, watercolour on paper, 30 x 40 cm

© Estate of Bhupen Khakhar, courtesy Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke

SJ If we refer back to the Indian context, Bhupen was doing something completely different from everybody in terms of painting. There were narrative painters, but the kind of subject matter he dealt with and his use of colour were distinct. His art also evolved over time. There’s something very interesting in that stylistic shift from those early, meticulous pictures to the looseness that starts to arrive in his work in the late 1980s and 1990s.

HH It’s something that makes his paintings very separate from the work of other artists, both English and Indian.

SJ Is there a particular picture of his that has a personal significance for you?

HH The De-Luxe Tailors, which he gave to me.

Bhupen Khakhar, The De-Luxe Tailors 1972, oil on canvas, 190 x 86 cm

© Estate of Bhupen Khakhar, courtesy Howard Hodgkin

SJ That painting is from his Tradesmen series – particularly poignant, because it depicts men doing ordinary jobs. In Indian art history they had never before been the subject of paintings. And then he treats them with such respect. They were not only the subject of the painting, but also his friends?

HH And lovers, in some cases.

SJ You included Bhupen’s work in an exhibition you curated at Tate in 1982, Six Indian Painters, which featured Rabindranath Tagore, Jamini Roy, Amrita Sher-Gil, MF Husain and KG Subramanyan as well as Khakhar. Can you tell me more about that show and the process behind your selection?

HH I really would have liked it to have been just about Bhupen, but there was no question of that. The gallery wanted something much more general. I found it difficult to include artists such as Husain, but I managed, by showing him as a photographer. His photos were very good, to my surprise. Other than that, I found it difficult. Geeta said: ‘Well, it will have to be done better next time.’ And it was done better, almost at once – I imagine by her, I mean actually, if not visibly, by her.

SJ So she played an active role in the selection of material, or you knew which artists you wanted to show and you chose the works?

HH No, that’s saying too much, because I didn’t think very much of most Indian painting then, apart from Bhupen.

SJ You included Sher-Gil and Subramanyan – very interesting figures who, like Bhupen, navigate Western and Eastern references.

HH Yes. I think I was disappointed at the selection that was possible. I’m not proud of that exhibition at all.

SJ But it’s quite well-regarded. One could say it has aged well in terms of the selection of artists.

HH I think it has, but I think Indian painting, as such, is far better than that show suggested.

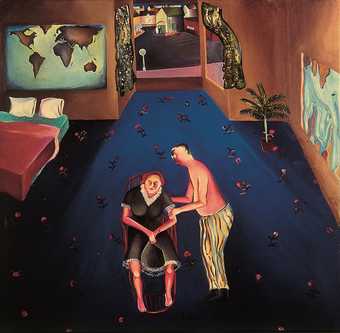

Bhupen Khakhar, The Weatherman 1979, oil on canvas, 101.6 x 101.6 cm

© Estate of Bhupen Khakhar, courtesy Chemould Prescott Road Archives, Bombay

SJ Why do you think there’s been such a gradual awakening to Bhupen’s practice generally, even in India? When he died he had shown at the Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, and he had reached a degree of acclaim, but it’s only now, 12 years after his death, that Tate is doing a show.

HH Because he’s a very original artist. Simple as that. But I also thought how extremely sad that he didn’t live long enough to see his work becoming sought after.

SJ Or the new scholarship that’s been generated around it. You have a great interest in India and own a collection of Indian miniatures. Bhupen had a wide range of interests, in Company Painting [a broad term for a variety of hybrid styles that developed as a result of European (especially British) influence on Indian artists from the early 18th to the 19th century] and all kinds of objects associated with high or low culture. Did you ever talk about his avid eye, when it came to such things?

HH Not at all.

SJ Did you ever talk about, maybe not specific paintings, but the act of painting, because you have very different ways of working?

HH Oh, yes, very different, but we had great respect for the other’s working habits.

SJ Did you ever discuss, for example, Western painting, such as Sienese painting, that he liked, and other Renaissance works?

HH Oh, yes.

SJ You did do a picture called From the House of Bhupen Khakhar 1975–6.

HH Yes, sadly it’s disappeared.

SJ Do you recall doing that picture?

HH I don’t recall doing it, but I knew I’d done it. His lover and servant, Pandu, was told by him to… well, look after me – in every possible way. I think that’s the discreet way of putting it. I was astounded. Pandu also gave me this wonderful waking-up cocktail every day which was… I never know how to pronounce it. It was mostly b-h-a-n-g.

SJ Bhang.

HH Bhang, that’s right, and he made particularly strong ones for me. Bhupen was very amused and said: ‘You’ll feel wonderful!’ I felt wonderful immediately. I did feel very loved by Bhupen and Pandu, but there were some rumblings in the distance.

SJ About them?

HH About them and me and Bhupen’s lover, V-, you know, it was all… Bhupen, naively, said: ‘It’s extraordinary, I can’t understand it, Mrs V- doesn’t like me!’ I thought nothing could be more likely.

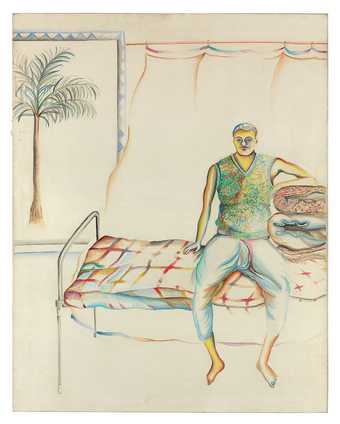

Bhupen Khakhar, Untitled (Portrait of Pandoo) 1977, oil on canvas, 106 x 83.8 cm

© Estate of Bhupen Khakhar, photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images

SJ Bhupen has made a number of portraits in his practice and so have you, but, again, they’re vastly dissimilar.

HH I think the way I paint people’s portraits has nothing to do with what others are trying to do. I’m going to have an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery next year, but it will be called Absent Friends. That, I think, to some extent, answers your question.

SJ Do you think Bhupen suffered in terms of coming to an understanding of who he was? He has reproached himself in interviews about the anguish it caused him; the guilt of being gay. He spoke about how difficult it was for him eventually to accept it, and then he did so, quite confidently.

HH Yes. Much more than I managed to, then.

SJ You once said that Bhupen’s paintings are ‘what life is, around you, here. He does not paint subjects that do not exist. He has been able to paint what he lives, nothing about art and everything about life – without hang-ups’. Do you miss him?

HH Oh, tremendously.

SJ Did you see Bhupen towards the end of his life, when he was ill?

HH Not often enough. I hadn’t realised quite how ill he was and I regret that very much.