Peter Henry Emerson, Gathering Water-Lilies 1886, platinum print from glass negative, 19.8 x 29.2 cm

Wilson Centre for Photography

In 1885 the photographer Peter Henry Emerson (1856–1936) and the painter Thomas Frederick Goodall (1855–1944) embarked on a project to photograph the people and landscape of the Norfolk Broads. Emerson was in the county to photograph birds for a planned ornithology book, and Goodall was already on the spot, painting in his houseboat studio. His subjects included his fiancée and her family, who were local people: Nancy and her father pose in The Bow Net 1885–6 and associated photographic studies.

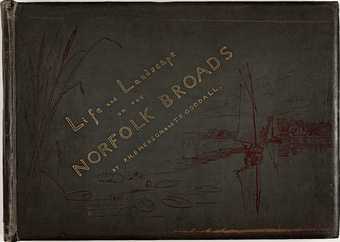

From their collaboration came the 40 photographs published in 1887 in Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads, a volume with a charming cover drawn by Goodall. This part of eastern England was becoming a popular destination for visitors, thanks in part to new train links with London, and with Cambridge (where Emerson had done his university degree). The tourists had a number of illustrated publications in which the Broads were portrayed as a kind of idyll apart from the modern world. Yet isolation meant hardship for rural people, whose traditional economies were in decline. Emerson and Goodall accompanied the pictures of the reed harvesters and marsh-men (and women) with essays on the life and customs that were disappearing.

Thomas Frederick Goodall, The Bow Net 1885–6, oil on canvas, 83.8 x 127 cm

Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

In subject matter and composition, their photographs echo Goodall’s paintings and those of his fellow artists at the New English Art Club (NEAC), including George Clausen and Henry La Thangue, both of whom Emerson met through Goodall in 1885. These painters adopted the modes of modern French art, particularly those of naturalist artists such as Jules Bastien-Lepage, who had visited London in the early 1880s and showed at the Royal Academy and the Grosvenor Gallery, where Goodall and others from the NEAC exhibited. They were also aware of the younger generation of impressionists such as Camille Pissarro, whose work was presented at Paul Durand-Ruel’s Bond Street gallery.

Naturalism and impressionism emphasised an attention to observed nature, seen and painted on the spot, not constructed in the studio. Yet Emerson and Goodall’s pictures are not candid documentary views. The figures are carefully composed, as Emerson’s large-format camera required timed exposures.

The images bear other markers of naturalism, for Emerson and Goodall incorporated ideas on physiological optics current at the NEAC. They adapted the focus of their camera lens to match the limitations of human vision, which was thought to be biased towards a central point of focus corresponding to a single area of awareness. Emerson also made a case for platinum paper as the print medium whose long tonal range and low contrast most accurately represents how ambient light is seen and perceived.

The platinum prints in Life and Landscape are subtle and beautiful, but they were labour-intensive and costly, and Emerson used the photomechanical processes of photogravure and half-tone printing for his other photographically illustrated books. Goodall contributed to four of those publications, but Life and Landscape is an extraordinary publication, so valuable that relatively few complete copies remain: many volumes were taken apart in the 1970s and 1980s and the precious platinum prints sold individually. It remains what it was in 1887, when Amateur Photographer praised it as ‘an epoch-making book’ combining ‘perfection of photography… perfection of reproductive processes, and… perfection of artistic feeling’.