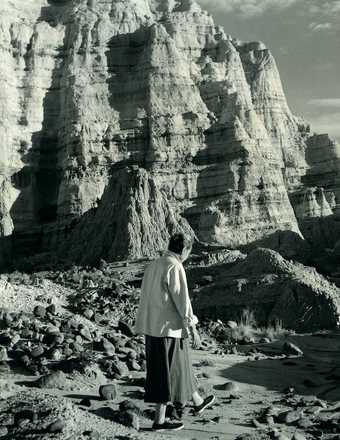

Tony Vaccaro, Georgia O’Keeffe, Taos Pueblo, New Mexico 1960, gelatin silver print on paper, 16.7 x 23.5 cm

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA; photo courtesy Michael A. Vaccaro Studios

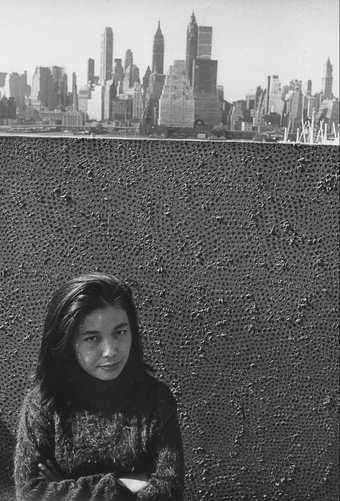

Yayoi Kusama

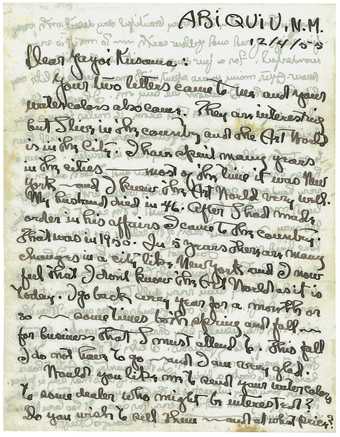

Of all the many remarkable people I have known in my life, the first I must mention is Georgia O’Keeffe. If she had not so kindly answered my clumsy and reckless letter to her, I am not sure I would ever have made it to America. She was my first and greatest benefactor; it was because of her that I was able to go to the USA and begin my artistic career in earnest.

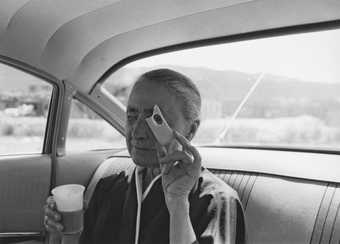

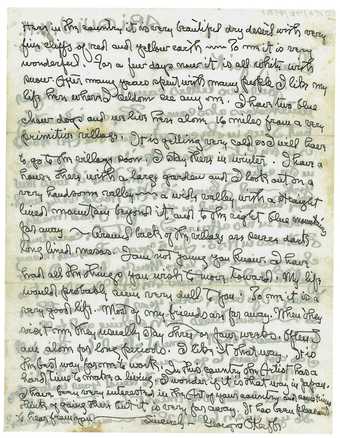

Letter from Georgia O’Keeffe to Yayoi Kusama, 4 December 1955

Courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

Letter from Georgia O’Keeffe to Yayoi Kusama, 4 December 1955

Courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc.

When I moved from Seattle to New York, I was thrilled to be in the city of my dreams. But New York was not remotely like post-war Matsumoto, and the ferocity of the place was such that I repeatedly plunged into bouts of neurosis. It was during one of these that O’Keeffe took the trouble to write me a letter in which she said that if I was finding New York so difficult to live in, I should come and stay at her hacienda in New Mexico. She enclosed photos of her house and garden, to give me an idea of life there. I was, and still am, astounded by such kind consideration for someone she had never even met. I can only attribute her kindness to her interest in the arts of Asia in general, and Japan in particular, and to the fact that I must have struck her as an oddity – a Japanese girl coming to America all on her own. My situation must have touched a nerve with O’Keeffe; perhaps she saw something in the works I had sent her.

She once paid me a visit in New York. This was in 1961, when I was in my fourth year in the city and living at 53 East 19th Street, in mid-town. I received a telephone call saying ‘I’m on my way’; 10 minutes later Georgia O’Keeffe was at my front door. I wanted to get a photo of us together, but my camera was out of film and there was no time to go out and buy a new roll, so I missed my chance. How I regret that now! My first impression was of the wrinkles on her face: I had never seen so many. They were about a centimetre deep and reminded me of grooves on the soles of canvas shoes. But she was a lady who simply exuded refinement. There was something truly noble and dignified about her. ‘I’m Georgia O’Keeffe,’ she said, stepping into the room. ‘You must be Yayoi. How’s everything going?’

Her bone structure was sturdy and angular, and in her quiet bearing was the proud loneliness of a great artist. She did not bustle about when she moved, but walked in a measured way. On her chest was a brooch by Alexander Calder.

O’Keeffe was very solicitous of me, asking if I was having a hard time making ends meet and if I wanted to come to her place in New Mexico. Though a very solitary person herself, she had gone out of her way to call on me and express concern for my welfare. She told me she would be happy to offer me room and board, but I reluctantly declined because I knew that only in New York could I become a star. New Mexico seemed far away and remote.

Yayoi Kusama with one of her Infinity Net paintings in New York, c.1961

© Yayoi Kusama

The scenery in the photos she had sent me looked as if it was in old Mexico. I was told that when the wind blew, tumbleweeds danced and whirled around, and the torrid air hit you like a furnace blast. That O’Keeffe was able to live so far from the centre of things and still maintain her fame and her status was a testament to the greatness of her art and how deeply it affected people.

Georgia O’Keeffe is among the top artists in history, and her paintings attained the very highest level. She possessed a certain genuine and deeply embedded spirituality, and it is largely to this that I attribute her greatness.

Judy Chicago

I have thought – and written – about O’Keeffe many times, beginning in the 1970s when I was formulating the idea of a female-based iconography, one that could challenge the male-centred art history that had been mistakenly assumed to be (and recently contested as) a universal perspective. When I was working on Through the Flower, the first volume of my autobiography, I attempted to get permission to reproduce O’Keeffe’s 1926 Black Iris painting, but was refused because she did not want to be seen as a ‘woman artist’.

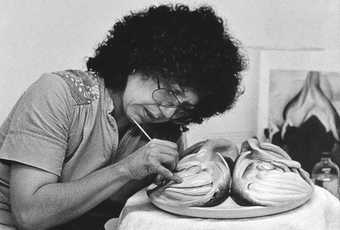

Judy Chicago working on the Georgia O’Keeffe plate for The Dinner Party, c.1976

Photo courtesy Through the Flower Archives

At that time, I didn’t understand her position. It was only later that I discovered that when her work was first shown, it was met by many male critics with the same type of incomprehension as my own The Dinner Party 1974–9 encountered almost 50 years later. Although many years had passed, art world perceptions had barely changed. Her paintings had been characterised as emanations of her womb (instead of the creative formulations of a brain and brush), while my plates were dismissed as nothing but vaginas on plates (rather than images symbolising the history of women in Western civilisation).

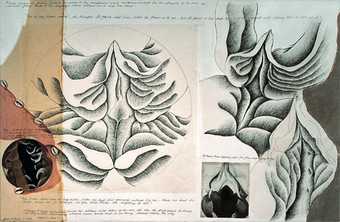

Judy Chicago, Study for Georgia O’Keeffe for The Dinner Party, 1974–9, ink and collage on paper, 61 x 91.4 cm

Photo courtesy Through the Flower Archives

Actually, I had an earlier encounter with O’Keeffe’s work, though I hadn’t recognised its significance at the time. When I was just out of UCLA graduate school in the mid-1960s, Rolf Nelson, my dealer, had a beautiful 24ft cloud painting hanging in his gallery. Although the price was modest – $35,000 – there was absolutely no interest in her work. But the feminist art movement of the 1970s changed this situation, as young artists (myself included) looked for antecedents for our own desires to be ourselves as women in our art.

For centuries women who wished to be artists were denied training. The most they could hope for was that if their fathers were artists, they would be taught in their ateliers. Even then, women weren’t allowed to study the nude, which virtually excluded them from the realm of high art as it required both life-drawing skills and an understanding of anatomy. If they were able to overcome these obstacles, they still had to fit themselves and their iconography into a tradition carved out by men, as earlier women artists such as Artemisia Gentileschi had been forced to do when she subverted the theme of Judith and Holofernes to accommodate her outrage at having been raped.

The advent of abstraction dramatically changed the artistic terrain. For the first time, artists could invent their own language to express themselves in ways that were previously completely inconceivable. Women artists took advantage of this new freedom, and O’Keeffe was one of the first to do so: she was a pioneer in translating a female sense of self into visual form.

Judy Chicago working on the Georgia O’Keeffe plate for The Dinner Party, c.1976

Photo courtesy Through the Flower Archives

In addition to being a landmark painter, her importance can also be measured by the fact that one of her works sold at auction for more than $44 million, the highest price for any woman artist, though that figure pales in relation to the amounts paid for work by men. Like many artists, I bristle at the notion that art’s worth can be measured by money, while recognising that art objects are value-laden icons, reflecting the values of society. It is common knowledge that women’s art does not command equitable market share. Although gender has ceased to matter as much as it once did, O’Keeffe’s desire not to be considered a ‘woman artist’ is – sadly – a long way from being fulfilled.

Elizabeth Peyton

I first really saw Georgia O’Keeffe’s work in 2005 at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe. Of course I knew who she was. I had seen her painting Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue 1931 in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and her work on the covers of calendars. But oddly, I never really thought of her as a painter. And even more oddly – no one ever thought to point her out when I was at school. I was in Santa Fe with my family over Christmas. It was a revelation to see her work. So beautiful, so powerful, so feminine! And huge, but still so humble. I remember that I saw some still lifes of purple fruit in which her mark-making was so full of life; there seemed to be so much integrity in them.

Georgia O’Keeffe, The Eggplant 1924, oil on canvas, 81.5 x 30.5 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, courtesy Art Gallery of Ontario

The museum was putting on a themed show of Warhol flowers and those by O’Keeffe. In the Warhol gallery I think I overheard the guide talking to a tour group, and she asked them to name five popular female artists who were alive – whoa! No one said a word. Then, finally, someone said: ‘Frida Kahlo!’ I was so moved, thinking about this. As we all know there are so many female artists, successful and otherwise, and yet none of them could name a single one. The other thing I thought a lot about after seeing Georgia’s pictures in real life is that while people often think they know an artist’s work, almost like a brand, nothing can compare with being in the presence of the work itself and letting it tell you what it is – not the cliché turned out by the outside world.

There are so many works of hers I love. After that visit I read a lot about her and looked at all I could. In a way I’m very moved by her charcoal drawings – the abstractions that her friend secretly sent to Alfred Stieglitz in 1917, which became her first exhibition. Just thinking of her in North Carolina (or was it Texas?), saying to herself that, in every part of her life – especially as a woman – she always had someone telling her what to do, but in her art work, that was the one place where no one could tell her what to do and she had to be free… and thus she made these pictures. I find her example of finding her way, truly being her own self, and making what she wanted to see, very inspiring.

Kaye Donachie

Georgia O’Keeffe was a prolific letter writer. A single letter written to the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay in 1934 documents their only known encounter. Poetically, O’Keeffe describes her impressions of their meeting in the form of a vision: unable to grasp the physical presence of her visitor, she describes Edna as a fleeting ‘hummingbird’ caught within the bleached white landscape of the studio.

I found this literary visualisation compelling and used her narrative as an emotive tone when making paintings for my solo show, Dearest, held last year at the Fireplace Project in the Hamptons, New York. The same summer, as I stood in front of O’Keeffe’s Summer Days 1936 at the Whitney Museum, echoes of this correspondence created a script that allowed me to look at the painting differently.

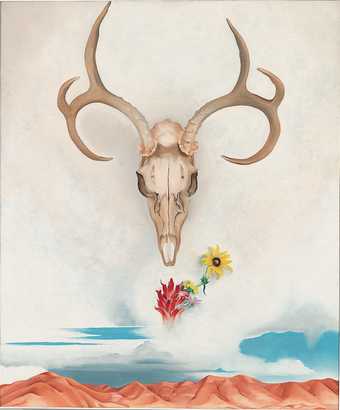

Georgia O’Keeffe, Summer Days 1936, oil on canvas, 91.8 x 76.5 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

It is a strange painting, and a painting of strangeness. Bones and blossoms float above rolling arid red hills. These forms are all painted with the same pitch and intensity. The painted space is constructed in layers forming a schism between the real and the imagined. This space is illuminated through colour and light – through a ‘touch’ that creates a haptic sense. We see a prelude for this in Alfred Stieglitz’s photograph Georgia O’Keeffe – Hands and Horse Skull 1931, which evidences that images can be a mode of seeing – groped, probed and caressed into becoming – seizing hold of life.

O’Keeffe’s Summer Days in its vividness attests to this haptic sense of the eye, a sense that grips the action of the hand, a sense that simultaneously grasps creation and destruction, between flesh and sense. Summer Days reminds us that painting is an ethereal stage on which images have the potential to appear and dissolve. Here, the studio is a desert and the desert a studio. Visions in the bleached sunlit sky merge with the white luminous clouds of an endless studio – a mirage of emergent images. Hovering like a hummingbird, it is an elliptical and poetic painting.

Lucy Stein

You imagine O’Keeffe lying prostrate on the wooden carpenter’s bench outside D.H. Lawrence’s Taos home, staring up at the night sky beneath the aptly named ponderosa pine. She stayed at this ranch belonging to Mabel Dodge Luhan on her first trip to the Southwest, five years after Lawrence had sloped back to Europe via Mexico with tuberculosis after writing St. Mawr there. The mental image that this summons of two of the titans of nature-worshipping modernism having cosmic and sexy thoughts beneath this ancient pine is as intoxicating as the picture itself.

Georgia O’Keeffe, The Lawrence Tree 1929, oil on canvas, 78.7 x 101.6 cm

© Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/DACS 2016, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, photo Allen Phillips/Wadsworth Atheneum

O’Keeffe did not mind what orientation The Lawrence Tree 1929 was presented at. Like a mandala, its impact is one of an innate recognition of wholeness and divinity any which way you turn it. None the less, she did specify how she preferred it to be hung: the shaft seen from below should loom forward like a protective arch over the viewer. After impressive receding length the trunk gives way to a tealish-grey coloured star-pocked night sky that is brought forward and then retreats as it appears at intervals through the dark mass of evergreen foliage and red synaptic branches. This is most thrilling where the white stars overlap the smudged edges of the thicket; the artist making the most of painting’s God-like ability to describe seeing through both eyes at once. Diffused patches of nebular warmth can be seen through the canopy directly above O’Keeffe/the viewer’s head.

I think this is a joyful painting to look at; it brings rushing back my experiences of when the magnificent impassiveness of nature feels like a protective shield against the conceits of mankind and his progress. In essence: the sublime (done the modernist way). I have admired O’Keeffe since my father brought me a print of one of her paintings back from New Mexico when I was a young teenager, and became fascinated by D.H. Lawrence in my early 20s. I generally feel a deep connection to the overarching modernist obsessions with inferring a macrocosmic limitlessness and describing a transitional state between epochs. In the current accelerationist context, with the potential of a transhumanist future close at hand, the works of these artists seem ever-more shamanic.