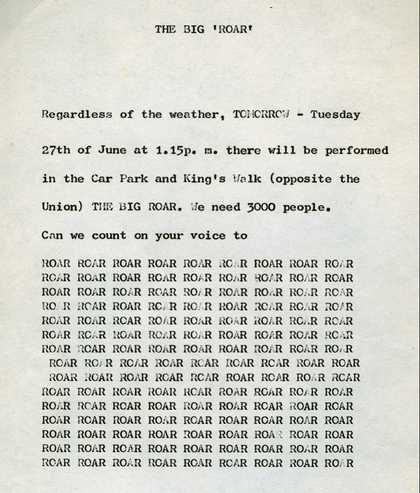

King Mob’s flyer for the Big ‘Roar’

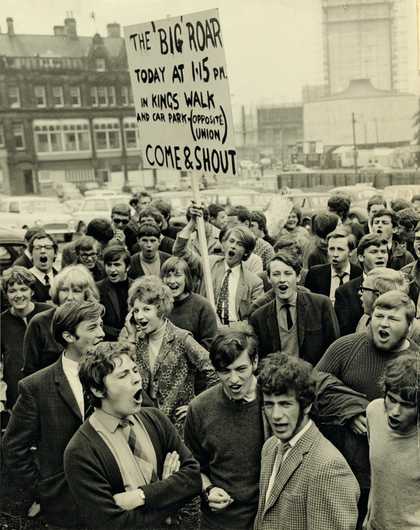

photo courtesy Tate Archive

Researching archive documents puts a demand on the items to speak to us, to make them communicate. This little flyer, in among a collection of loud agitprop and anti-art manifestos, suddenly put the demand on me. Not just to speak, but to roar. On the one hand it is promotional ephemera, on the other it’s a disquieting call to arms. This small piece of paper seeks to provoke something much larger than itself. Setting a time and a place, it challenges the addressee to take part in a demonstration of radical statement. Now, as an archive document, it challenges the researcher to imagine that moment. Did 3,000 people assemble in the street and roar?

The event is framed as a kind of happening rather than specific protest that takes on a line of politics. In other words, the intention of the Big ‘Roar’ seems to be weirdly to radicalise public space, using confrontational but absurd tactics. As inspired by Tristan Tzara, the roar itself is meaningless, non-signifying sound. We might see the voices behind it as likewise anonymous, the lumpenproletariat that the authors of the flyer spoke as and for.

King Mob, as the anti-art activist group was called, was the English section of the Situationist International formed in the late 1960s, having taken its name from Newgate Prison wall graffiti at the 18th-century Gordon riots. The oxymoronic name incidentally, combining sovereign and furious crowd, again evokes the regicidal roar proposed in this item. The King Mob collection at the Tate archive, made up of journals and posters, gives a good indication of the group’s references to dada, surrealism, comic-strip scatology (i.e. the Bash Street Kids), Russian nihilism and political hooliganism, with affiliations to New York anarchist groups Black Mask and Up Against the Wall Motherfucker. As ‘gangsters of the new freedom’, KM used bully-boy humour, toilet wall sloganeering and counterculture street politics. Its way of anglicising the SI was to oversimplify it, to use more ‘wit and better timing’, revelling in the crudity of what now reads like a mix of dodgy brosocialism, anti-hippy, anti-intellectual sensibility and proto-punk satire.

The Big ‘Roar’ notice has all the cues of the contingent 1960s revolutionary anti-aesthetics. The block of typewritten ROARS in the middle resembles a concrete poem, or the score for a dada sound poem. Each word technologically labours a mass of bodies, with a radical indent in the middle for accent: the sound of the revolution should ‘be the sound of the bacchanalia’. The text is the dream of a crowd, which continues to transmit from this flyer today. More like the rally of cry of history than revolution, it’s all ruin and potential.

So did the Big ‘Roar’ happen on 27 June at King’s Walk? A large photo in the same folder portrays a pack of young white people with compelling sideburns, mouths agape in apparent roar, or maybe laughter. Or they could be yawning.