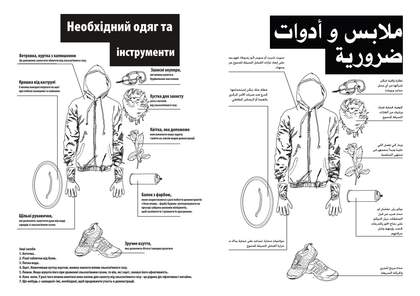

Anonymous leaflet circulated in Cairo in early 2011, offering protestors advice for peaceful mass demonstrations, confronting riot police and besieging government offices

Courtesy Public Intelligence

The relationship between art and protest has never been a stable one. It is also a relation that perhaps suffers from being posed in the abstract. Who could say what work artists would have made outside of a context of political turmoil, war and social unrest? And yet at the same time we often feel uneasy at demanding that art always be political, that it always respond to whatever historical events are emerging around it: can’t art also be an escape from violence, commentary, taking a stand?

Art can also seem to be at something of a disadvantage when it comes to immediacy – a protest may be more or less spontaneous, but art surely demands time and reflection. This only becomes a problem, though, if we adhere to a particularly narrow conception of art – what about home-made protest banners? Protesting itself might be counted as a kind of performance, a choreographed relation between opponents of a regime and the forces of reaction. A particularly beautiful example of protest art appeared on a leaflet in Egypt in 2011, depicting an empty hooded top, running shoes, protective glasses, a saucepan lid and a rose to symbolise peace – certainly a useful text in the midst of street battles, but one that also represents the aesthetic desire for a new world to come.

Teresa Margolles

Flag 2009

Fabric, blood, earth and other substances, 2980 x 1880mm

© Teresa Margolles, courtesy LABOR

But some political situations are more entrenched and art’s response more complex. The Mexican artist Teresa Margolles has created a number of works that demonstrate the West’s complicity with the drug wars of South America, bringing the violent deaths of young victims of the drug trade directly into art spaces. In Flag 2009, notably displayed at the Mexican Pavilion at the Venice Biennale next to an official EU flag and a Venice city flag, she hung material that had been impregnated with blood and dirt at drug cartelrelated execution sites in northern Mexico. The title of her show, What Else Could We Speak About?, reminded audiences of the luxury that comes from ostensibly being able to turn away from violence in other parts of the world. And yet Margolles’s work is also about the impossibility of ignoring global networks and the way in which one part of the world benefits from the other: the Mexican Pavilion’s card for that year, designed by her, had on one side the picture of a man brutally murdered and on the other the instruction: ‘card to cut cocaine’.

Memory in the present and of the past is a strong theme of much public political art, particularly murals. Often painted anonymously or by relatively unknown artists, murals in areas of political turmoil, such as Derry in Northern Ireland, serve to remind passers-by and residents of the events of Bloody Sunday in 1972, as well as point to continued struggles against the British army and state. Paul Graham’s photography series Troubled Land 1984–6 deals with the same question but in a much more withdrawn way, focusing not so much on the spectacular public art, but on smaller, though no less loaded signs: a pavement painted in Republican colours, a Union Jack caught in a tree, graffiti on a road sign.

Brixton mural by an anonymous artist commemorating the death in police custody of Sean Rigg

© Mike Urban/brixtonbuzz.com

In London many Greater London Council commissioned murals have been destroyed, neglected or painted over, while in Tehran and other cities they continue to commemorate massive loss of life in war, the mendacity of the USA, and the prophet and the 12th Imam, face covered, holding bodies of wounded soldiers, recalling Magritte’s Les Amants 1928 with their faces anonymised by white cloth. But new murals do still emerge from time to time. In 2015 one appeared in Brixton commemorating the deaths of residents who died in police custody – Ricky Bishop and Sean Rigg – their faces united in death and dignity beneath arches due to be demolished in the name of modernisation.

The question of art’s relation to political time unites the immediate moment of revolution with the long, slow, hard process of remembering and trauma. Not all political art needs to be large and public to have a profound impact. Chittagong artist Somnath Hore’s 1970s small, delicate, abstract paper pulp series Wounds remembers the Bengal famine of 1943, the partition of India and Pakistan and other violent events. The cement moulds he used were themselves mutilated by knives and other tools – the resulting damaged prints, stained with red, resemble torn skin, scars, tears, a reminder of the fragility of the human body and its capacity to be marked.

Political art made in a particularly volatile context often carries with it the risk of arrest and censorship for the artist. Despite Pratuang Emjaroen not identifying explicitly with political organisations in Thailand in the 1970s, his surrealist take on the military put-down of activists, Red Morning Glory and Rotten Gun 1976, led to confrontation with the authorities. The painting is now part of the Singapore Art Museum’s collection. Exiled Chinese artist Wang Keping’s Silence 1979, a wooden sculpture of a man’s head with a plug in the mouth – a commentary on censorship following the Cultural Revolution – was pulled from a 2013 Beijing retrospective of his work, the artist and gallery director themselves deeming the work still to be too politically contentious.

Malangatana Ngwenya

Untitled 1968

Ink on paper, 370 x 510mm

© Malangatana Ngwenya, with compliments from the Gallery of African Art (GAFRA)

There are those artists who have spent significant time in jail for their political convictions. Malangatana Ngwenya, the Mozambican Marxist painter and poet, was arrested by the Portuguese secret police and imprisoned in the 1960s. His art, including many murals, often depicts multiple bodies, crowding and struggling against the oppressive Portuguese regime. The dream-like fantasies also invoke images of danger, fanged opponents ready to attack those who stand up for independence. Ngwenya’s works, while oneiric, are clear in their assertion that the political situation he depicts is intolerable – beauty against violence.

But political art sometimes raises another difficult question: what happens when beautiful images are made of terrible things? This problem is tackled in a recent book by David Shields, War is Beautiful 2015, where the author reflects on the relationship between art and the photographing of war for major news outlets such as the New York Times. In it, he suggests that:

Art is an ordering of nature and artefact. The Times uses its front-page war photographs to convey that a chaotic world is ultimately under control, encased within amber. In so doing, the paper of record promotes its institutional power as protector of death-dealing democracy and curator of Western civilisation. Who is culpable? We all are; our collective psyche and memory are inscribed in these photographs. Behind these sublime, destructive, illuminated images are hundreds of thousands of unobserved, anonymous war deaths.

Pratuang Emjaroen

Red Morning Glory and Rotten Gun 1976

Oil on canvas, 1350 x 1650mm

© Pratuang Emjaroen, collection of National Gallery Singapore, image courtesy National Heritage Board

Again the question of complicity is raised, as it was in Margolles’s work. Art that glamorises what should be condemned leads to a series of tricky moral questions: how should destruction be presented? Can it only be written about rather than shown? How should artists respond to violence without falling into the trap of beautifying horror? Outside of its possible propagandistic function, political art can, however, often un-bury acts that have been forgotten. Take Redza Piyadasa’s 1970 installation May 13, 1969, an upright coffin painted with the Malaysian flag and placed on a square mirror. The date refers to a still relatively undiscussed mass killing in Kuala Lumpur when sectarian violence broke out between the Malay and Chinese populations. Art can commemorate and remember the past, but it can also serve as a memory in the present, a sign or symbol ensuring that forgetting is not possible, no matter how uncomfortable the debate it instigates might be. The work of Theaster Gates is a case in point. In his Civil Tapestry project, for example, segments of firehoses appear to comprise an abstract composition. However, the dates and locations of the firehoses themselves – ‘1962’, ‘Compton, Calif.’ – tell another story: 1962 saw riots erupt over racial integration in Mississippi, and hoses were turned on protestors in Alabama around this time too. The ‘neutrality’ of the object in the gallery is overlaid with the political and historical significance of its earlier purpose.

There is, of course, no one way that artists should respond to social and political upheaval, whether they are participants in a movement in the present, uncovering uncomfortable memories, revealing the presence of complicity, or commenting on contemporary censorship. But art that engages in questions of state violence, of the propagandistic use of war imagery, of global asymmetries, of struggles for national liberation and civil rights, serves to remind audiences everywhere that to stand back from politics, to disengage in social questions, is a possibility far rarer than it might sometimes seem. We should worry instead about those periods where there is no artistic commentary or intervention: for those are truly times without humanity.