Andrew Gilbert

Fix Bayonets and Die like British Soldiers Die 2007

Dimensions variable

© Andrew Gilbert, courtesy the artist and Ten Haaf Projects, Amsterdam, photograph by Roman März

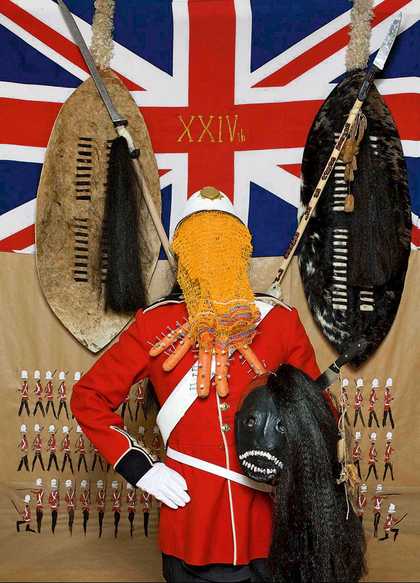

Hew Locke

Congo Man 2007

C-print, 23146 x 18161mm

© Hew Locke, all rights reserved, DACS 2015, image courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, London

Simon Grant When we think about the British Empire, it immediately conjures up some rather clichéd perceptions about a country’s past. And the way that history is being remembered, taught and discussed has remained problematic for some, while misinterpreted or ignored by others. Do you think the notion of empire has any relevance today?

Hew Locke For me, the legacy of empire is all around us on a daily basis – not just the variety of ethnic backgrounds that we have living in the UK, but the buildings and public statues you see in cities across the country that came into being out of the economy of empire.

Andrew Gilbert Many conflicts in the world today are the result of the arbitrary borders created by European empires. Also, as in the 19th century, the invasions and occupations of foreign countries today are motivated by control of resources rather than ideals such as democracy or civilisation. The language of propaganda and demonisation of the exotic enemy is also very relevant now. The red uniform is still worn for ritualistic parades that are used to enforce the idea of nation and power – which also make very good images for postcards for tourists.

SG You have both responded to this legacy in very different ways, but where does the initial interest come from?

AG My obsession began as a child after seeing the 1964 film Zulu, which is about the Battle of Rorke’s Drift between the British and the Zulus. It has been many people’s introduction to the idea of the British Empire story. I wondered why a film about shooting black people in South Africa was so popular – and why it was always shown at Christmas. As a child I compared the Zulu War with the Jacobite rebellion in Scotland: a charging ‘primitive’ army facing lines of red coats with superior weapons. It was this strange romanticised view, which I then began to parody. I later studied primitivism in modern art at university and how Western artists romanticised ‘savage’ art. I began to make my own European fetish objects to show how primitive European society is.

HL For me, it was growing up in a post-colonial society in Georgetown, Guyana. Signs of the empire were all around me. The architecture was Tudor gothic. I went to a school run by Anglican nuns. And I was being taught about Alfred the Great and English kings – all completely irrelevant to my life in Guyana.

Hew Locke

Burke 2006

C-print with mixed media, 2440 x 1120 x 150mm

© Hew Locke, all rights reserved, DACS 2015, photograph by FXP Photography, London

SG How have you responded to that?

HL By making the semi-invisible more visible, and luring in the viewer. In Bristol there is a statue of Edward Colston (1636–1721), and many buildings bear his name – Colston Towers, Colston School and Colston Hall. The statue depicts him as a great man, with his chin resting on his hand as if pondering noble thoughts. But he made his money as a slave trader. He was an active member of the Royal African Company and a founding member of the Merchant Venturers. I made him into a fetish figure covered in cowrie beads, which were used in Africa for trading slaves. For me, it’s about the link between the nail fetish figures produced by the Songye tribe in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Catholic votive objects: one is seen as uncivilised and the other civilised. There’s an ongoing debate as to whether to tear the statue down and change the name of Colston Hall – an amazing music venue, yet Massive Attack, for example, have refused to play there.

AG And in South Africa in recent months they have been vandalising various statues of Queen Victoria.

HL I arrived in Guyana aged six (from Scotland), just at the time of independence in 1965. The new government took down the statue of Queen Victoria from outside the main law courts and dumped it at the back of the botanical gardens in the 1970s. She had already been damaged by dynamite by people protesting against British rule in 1954. But a new president came into power, and in 1990 he decided to put it back in place, but still battered. This example is about a colonial and neocolonial relationship – a complicated journey, all in one statue.

AG There is a flipside example that happened a few years ago in South Africa. At King Shaka International Airport in Durban there was a statue of Shaka Zulu flanked by two cows. The Zulu royal family complained because he was depicted without his weapons of war. He looked too peaceful. So now they have taken him away and you just have the cows standing there. Also, I think Cecil Rhodes has just been removed from the University of Cape Town under student protest.

Charles Edwin Fripp

The Battle of Isandlwana, 22 January 1879 c1885

Oil on canvas, 142.2 × 223.2cm

National Army Museum, London

Andrew Gilbert

During the Battle of Rorke’s Drift 2014

Acrylic on canvas, 700 x 1000mm

© Andrew Gilbert, courtesy Sperling, Munich

SG You have both used the word fetish. Andrew, what has been your route into this?

AG A European war memorial or a regimental banner for me is similar to a Benin fetish object – they are sacred objects that serve a ritualistic function. During the First World War the British accused the Germans of hammering nails into war memorials – a savage, dark ritual. The Protestants destroyed Catholic idols during the Reformation. In my sculptures British soldiers are decorated with carrots and nails, and wear potato sacks as veils. They become primitive fetish idols. I like to create my own ethnographic military museum with the British figures in the vitrines and the Zulus on the outside looking in at these strange idols. The Zulus and the British wore leopard fur and feathers, and the Zulu regiments were divided by the colour of their cowskin shields. The Zulu army was highly disciplined. One could say it is quite strange to dress in a bright red uniform and shoot exotic people who are defending their land. But one must also acknowledge that Shaka Zulu did in South Africa what the British Empire did to the world: invaded and slaughtered.

HL I have been interested in ideas of what a nation takes to invent itself. What do people hold up as their symbols? What become the fetishes? In Windsor Castle there’s a purple velvet pillow on which sits a Bible with a bullet hole in it, apparently the same one that General Gordon was holding while he died. When I talk about fetish, that’s what I mean; it’s quite a strange fetish object of empire.

Hew Locke

Sikandar 2010

Mixed media, 300 x 600 x 400mm

© Hew Locke, all rights reserved, DACS 2015, courtesy the artist and Hales Gallery, London

SG As well as the General Gordon mythology, the Zulu story has been romanticised. Andrew, you have also incorporated other mixed histories of empire to create what we could say is a very different perspective from what the average schoolchild might read about.

AG The most popular painting in the National Army Museum in London is Charles Edwin Fripp’s The Battle of Isandlwana , 22 January 1879 c1885, which shows the annihilation of British troops in one of the worst disasters suffered by the army at that time. The Zulu film has helped its popularity. For During the Battle of Rorke’s Drift 2014, as well as showing an exaggerated blonde and blue-eyed Michael Caine from Zulu, I added elements from Emil Nolde’s nine-part Life of Christ 1911–2. I had also become obsessed with his paintings Masks Still Life III 1911 and Trophies of the Savages 1914, in which he’s representing savages hacking off heads in Polynesia. At the time the Germans were hacking off heads in Namibia and sending them back to Berlin to measure them for racial science. The propaganda version of history is very different from reality. At the end of the film, for example, we see the Zulus sing a song to the British, as if in admiration, and they leave. In fact, after the battle every wounded Zulu was either bayoneted or shot through the head, as was the case at the battle of Culloden in 1746. Then the British burned down the capital of the Zulus, Ulundi. In return, Queen Victoria gave the Zulu king a Bible. It is the equivalent of the Zulus turning up and burning down London, and giving us a medicine man’s fetish.

Emil Nolde

Masks Still Life III 1911

Oil on canvas, 730 x 775mm

© Nolde Stiftung Seebüll, courtesy The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

SG But why is there this lingering interest in various aspects of the colonial story?

HL If I’m honest, if I think about Britain going down to the Falkland Islands, or heading off to Libya, that seems like a contemporary colonial attitude – a hangover from empire. Think about how the Western countries each reacted to the Ebola outbreak. Britain went to Sierra Leone, a former colony. France went to Senegal, a former colony. America went in to Liberia because it used to be a colony of the American Colonisation Society.

AG And often it was about resources and protecting interests – as when the East India Company first invaded Afghanistan in 1839. When one is aware of the motives for the imperial invasions, one can better understand the reasons today for Western military occupation and the deep resentment against the foreign invader.

HL Yes, that’s very true. I made a proposal for the Fourth Plinth called Sikandar in 2010 based on an existing statue of Field Marshal Sir George White (1835–1912), who, among other things, won a Victoria Cross during the Second Afghan War (1878–80). I was making links between the war which is still going on in Afghanistan and Alexander the Great, and how history tends to come full circle. While doing the research for this particular piece, I went to the Helmand exhibition at the National Army Museum. On one of the wall texts was a story by a British captain from about 2002 who went into an Afghan village after the Taliban had just been defeated. He talks to villagers, trying to win hearts and minds, when one Afghan says to him: ‘Your lot burned down the bazaar.’ He goes back to his colleagues at base and tells them he thinks the paratroopers have run amok, and asks if it’s true. Eventually, one guy says, yes, we did burn down the bazaar, but during the First Afghan War (1839–42)!

AG We have our national heroes and glorious last stands, but we know nothing of their dead. Now the Afghans have built a museum for the jihadists who fought against the Russians. The sideburns of the dilapidated mannequins at the Rorke’s Drift museum in KwaZulu-Natal are falling off, while the Zulus are building new museums to their own imperial history.

Agostino Brunias

Dancing Scene in the Caribbean (1764–96)

Tate

SG How does all this make you feel about the forthcoming Tate Britain show and its relevance today?

HL I think the Agostino Brunias painting Dancing Scene in the West Indies 1764–96 (from Tate’s collection and in the show) has relevance to the Caribbean today in how society there breaks down from a class and race point of view. People have the idea that the Caribbean is made up of one race, but it’s more complex than that. It is a ‘pigment-ocracy’. The lighter your skin, the higher up the social ladder you go. It’s a highly sanitised version of slavery. The reality in the past was horrendous – much worse than slavery in America. The dynamic behind this image is that the light-skinned women are free, while those who are bare chested are slaves. It’s nuanced, but the people there would understand what it was about. Of course the subject of slavery and all this Caribbean stuff is very complex – it’s really quite messy.

SG Hew, there is a work in the exhibition by your late father Donald Locke called Trophies of Empire 1972–4. What do you think about it in the context of this discussion?

HL It’s weird. The thing me and my dad have in common (and it took me years to realise this) is that all his work was about being black and living in Britain. I was very young when he was making that piece, but I didn’t relate to any of his work until I saw it in The Other Story exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1989.

SG Is there – and this connects with the Tate show as a whole – still a tendency to see that work as not actually being integrated into the mainstream?

HL Yeah, it was criticised and sidelined, and it never quite recovered from that. I think things have changed now. A lot of my early work, for example, was a reaction to people saying: ‘Where do you come from?’ That was extremely irritating, so I covered it in export signs. For my dad, there was a similar thing whereby he was deemed to be from somewhere else. It’s taken many years for things to be different. Look how long it’s taken for Frank Bowling to be recognised as a really important painter.

SG Interestingly, you have both portrayed the reversed roles of dominant figures in the colonial period…

AG I created the figure ‘Shaka Napoleon’ as Napoleon and Shaka Zulu are often compared in terms of military strategy but were also both deranged dictators. Another work of mine Andrew Emperor of Africa 2010 is a mixture of all these ideas about absolute power and total lunacy. Sometimes he sketches flowers with General Gordon, on other days he drinks instant coffee with the Mahdi – it depends on my mood.

HL My series How Do You Want Me? 2007 has links with James Sant’s painting Captain Colin Mackenzie c1842/4 in that they’re both about people going native, or dressing up as or taking on the persona of those you’ve either conquered or had close ties with via empire. (It’s a bit like Marie Antoinette at the bottom of the garden in Versailles playing the shepherdess.) Congo Man from the series is called that for specific reasons: it’s about conflict or ideas of conflict in the Congo, but also it’s named after a famous Caribbean calypso by Mighty Sparrow, which is totally outrageous and comes directly out of the colonial experience. The background camouflages the Queen’s motto ‘Honi soit qui mal y pense’ (‘Evil to him who evil thinks’), which I’ve used for quite a while because it cuts both ways. But again the whole thing has turned into this scary, exotic guy who is both colourful and attractive – and play-acting from a position of power.

AG Also, what is interesting is that when you look at some countries now, you can see a similar role reversal – in particular with the African chiefs in the past 20 years. For example, they put on their military-style uniform, with medals and the epaulettes, because these have become universal power symbols. Idi Amin would be the most extreme example.

HL Or someone like Emperor Bokassa of the Central African Republic, who basically decided: I’m Napoleon! He had a coronation, and wanted the Pope to visit his country. He thought, how can we do that? Build a cathedral and then get him to inaugurate it. And that’s how he got the Pope to come. What was even stranger about this was that while Bokassa was imitating a colonial scenario, he was being backed by a former colonial power. Of course, this was never going to last. These guys all come crashing down sooner or later.