In the modern period in art the relationship between a work and its image became ever more complex. Anticipating today’s digital culture, in which high-resolution 360-degree photography and slick installation shots provide us with our first – and sometimes only – encounter with a particular piece by an artist, in the early 20th century works by Barbara Hepworth and her international contemporaries became known to many primarily as reproductions in avant-garde magazines and specialist books, or, as the amount of coverage given over to the arts in mainstream media increased, in newspapers, cinema newsreels and television documentaries.

In a 1932 essay Hepworth’s friend, the art critic Herbert Read, described the camera as ‘a chisel of light, cutting into the reality of objects’. His analogy between the tools of the sculptor and the photographer and filmmaker is an appropriate one in this instance. Hepworth’s art proved a wonderful subject for photographers and film directors, who delighted in capturing the forms, textures and angles of her sculpture.

Barbara Hepworth, photomontage of Helicoids in Sphere 1938, and the entrance hall of the Doldertal apartments in Zurich by Alfred and Emil Roth with Marcel Breuer. Architectural Review © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

The first film about her work was Dudley Shaw Ashton’s Figures in a Landscape of 1953, funded by the newly established British Film Institute’s Experimental Film Fund and combining the words of the archeologist and writer Jacquetta Hawkes spoken by poet Cecil Day-Lewis with a score by Priaulx Rainier. Somewhat surreal sequences placed her sculpture alongside ancient monuments or on the beach. Despite conveying more of the director’s vision than the artist’s, it set the tone for future portrayals, especially in the emphasis on the connection between her art and the Cornish landscape.

Hepworth’s work featured in a range of films in the 1950s and 1960s, including newsreels distributed internationally, and more reflective pieces such as Warren Forma’s Five British Sculptors (Work and Talk) of 1964 or John Read’s Barbara Hepworth of 1961 for the BBC. Aware of the impact of the moving image for her reputation, she was keen to ensure her artistic ideas were correctly represented. Archive correspondence reveals her being fairly prescriptive in her dealings with filmmakers, requesting detailed scenarios in advance or advising on the best locations and specific times of day for filming, as with a documentary for Westward Television in 1968.

Barbara Hepworth working on the armature of Single Form in the Palais de Danse, St Ives

Hepworth Photograph Collection © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Photographs were easier to manage. In addition to those taken by Studio St Ives and other professional fine art photographers as a record of her works, she responded to requests to take pictures of her in her studio. And she also commissioned photographs, such as the aerial images of her sculpture garden in St Ives, or those of Single Form 1961–4 outside the UN headquarters in Manhattan (when she was not satisfied with the first set provided). Letters between Hepworth and photographers including Cornel Lucas, Ida Kar and Jorge Lewinski reveal the strict control she maintained about which prints or negatives were to be released, and how the images should be used in publication. Writing to Bryan Robertson, director of the Whitechapel Gallery, about her 1954 exhibition catalogue, for example, she warns:

It is terribly important that the photography should not be cut in any way at all. If even a fraction of the bottom or top is removed, it prevents one feeling that the carving is large and merely looks about six inches long. With the roof and gutter in the background the whole thing manages to achieve a scale.

Revealing her knowledge of the photographic process, she goes on to describe an image of her 1953 work Monolith (Empyrean):

The polished parts of the blue marble came out black and distorted with polychrome film. After several attempts this photo was got with old chrome film + special lense. The dark edges which remain are not faked – they are part of the [carving].

Figure for Landscape 1960 on the steps of Tate during Barbara Hepworth’s 1968 retrospective

Hepworth Photograph Collection © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Hepworth’s views on the photographic representation of her work were undoubtedly informed by her own experience with the medium. Between about 1933 and 1944 it was actually the sculptor herself behind the camera, documenting her work for her records. She learned to select appropriate backgrounds and how to light and angle her sculpture to convey its texture and mass. The earliest examples of her photography on display in the Tate Britain exhibition are found in the family albums assembled while living in her Hampstead studio with Ben Nicholson. Each page is a playful combination of pictures depicting her sculptures, Nicholson’s paintings and domestic ephemera, juxtaposed with views from the studio’s various vantage points and photographs of the artists at work or at rest. Echoing the eclectic design of the studio interior, the books communicate a conception of art and life intertwined, a mise en scène that the couple, significantly, translated into exhibition spaces for joint shows at Arthur Tooth and Sons in 1932 and the Lefevre gallery in 1933, both in London.

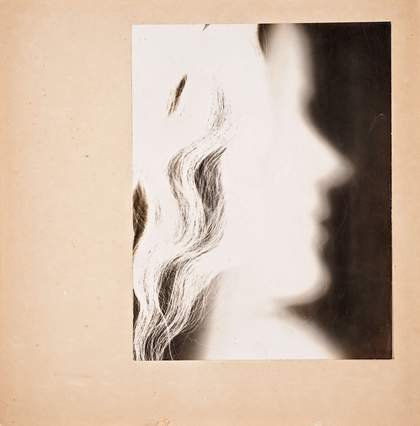

Barbara Hepworth

Self-portrait photogram 1933

© The Hepworth Photograph Collection

As the album images seem to show, for Hepworth photography was not simply a means of disseminating her work among a wider audience, but also a tool that enabled her to reflect on her art. She experimented with different photographic techniques, creating photograms, such as Self- Portrait Photogram 1933 (see Tate Etc. issue 29), which resonate with the incised profiles that feature in sculptures made around the same time.

Her particular motivation appears to have been the question of how to represent three-dimensional sculptures in a flat image – and one possible answer was the double-exposure of Two Forms 1937, which, by combining a multiple perspective, evokes a sense of the viewer moving around a work. Yet the singularity of this picture among her papers prompts us to conclude that she felt she had not yet solved her problem. Further experiments reveal her ambition as an artist, such as the series of seven collages for which she cut up photographs of her existing sculptures and pasted them, enlarged, into images of landscapes or modernist buildings, thus speculating how her work would appear if commissioned on a larger scale and in relation to nature or architecture.

Barbara Hepworth Double exposure of Two Forms 1937

© The Hepworth Photograph Collection

Hepworth’s sensitivity during her lifetime in managing the representation of her work in photographs and on film, therefore, belies not only a sophisticated understanding of the power of the image to stimulate critical, popular and commercial interest in her work, but also an awareness of how to use it as a means of experimentation.