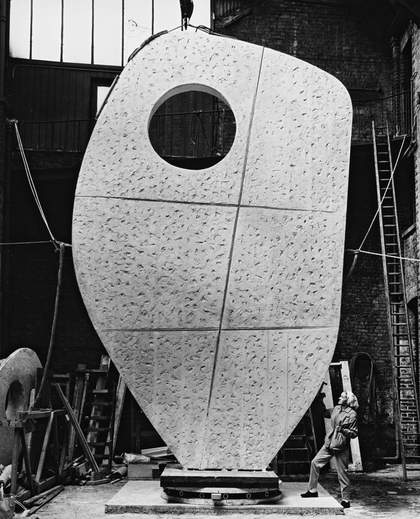

Barbara Hepworth with the plaster of Single Form 1961–4 at the Morris Singer foundry, London, May 1963

Hepworth Photograph Collection, photograph by Morgan-Wells, courtesy Morris Singer/Bowness, Hepworth Estate

The dominant view of Barbara Hepworth has been largely defined by where her work is most commonly seen – both the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden in St Ives and more recently The Hepworth Wakefield. However, the lesserknown Hepworth story is how she became a major international artist, showing in museums and commercial galleries across the world from a relatively young age.

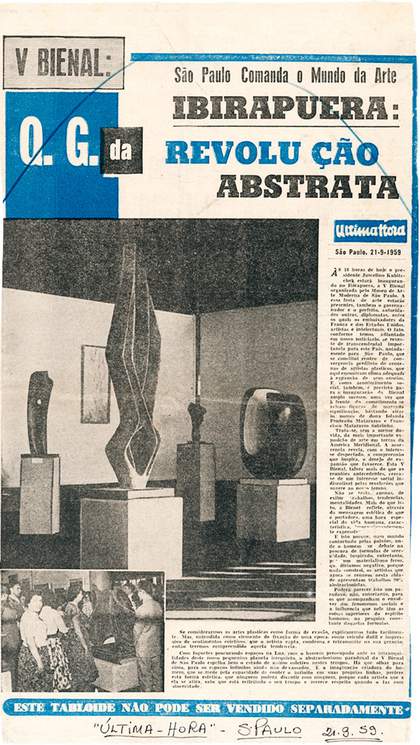

She was, along with Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson and Francis Bacon, one of Britain’s most important artists, and there are several key moments that reflect the internationalism of her career. She showed in New York at the Durlacher Galleries as early as 1949, and the next year represented Britain at the Venice Biennale. In 1955 an exhibition of her work organised by the influential Martha Jackson Gallery (a New York dealer representing the abstract expressionists among others) opened at the Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis, and then toured to public institutions across the United States and Canada, including Nebraska, San Francisco, Buffalo, Toronto, Montreal and Baltimore. Four years later she won the Grand Priz for sculpture at the São Paulo Biennial, after which her works toured several Latin American countries, including Uruguay, Argentina and Venezuela. It is significant that her work found an audience in Latin America – a recognition, perhaps, of the beauty and perfection of its forms that spoke to a particular, abstract idea of modernism.

Barbara Hepworth’s Three Obliques (Walk In) 1968 installed beside Aristide Maillol’s Action in Chains 1906 at Hakone Open-Air Museum, 1970

Hepworth Photograph Collection © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Hepworth’s work soon came to stand for a certain kind of modernity, epitomised when some of her sculptures were chosen to be exhibited at the inauguration of Gerrit Rietveld’s rebuilt sculpture pavilion at the Kröller-Müller Museum, the Netherlands, in 1965. Here visitors could see the deliberate dialogue being created between the subtle and various textures of the rectilinear modernist structure and her organic bronze sculptures.

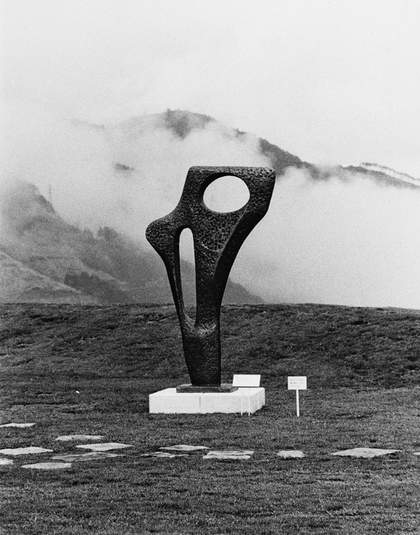

The appetite for her abstraction was taken up enthusiastically in Japan when in 1970 she was invited to show at the Hakone Open-Air Museum. For the display she chose a selection of her large rectilinear sculptures from the late 1960s and placed these (as the photograph here shows) in the dramatic landscape, with Mount Fuji as a backdrop. A version of the exhibition went to Kyoto.

Barbara Hepworth’s Figure (Archaean) 1959 at Hakone Open-Air Museum, 1970

Hepworth Photograph Collection © Bowness, Hepworth Estate

The figure of Hepworth as the internationalist was anticipated in the 1930s when she and Ben Nicholson actively sought to become part of an international network of artists that would include Auguste Herbin, Piet Mondrian, Jean Hélion, László Moholy-Nagy, Georges Vantongerloo, Max Bill and Alexander Calder, as well as Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Together they corresponded and collaborated on publications and exhibitions.

For example, Nicholson and Hepworth joined the Paris-based international group Abstraction-Création led by Herbin and Vantongerloo, while Hepworth was active in contributing to both Axis and Circle magazines. These publications become a major vehicle for the artists, and arguably more important than the exhibitions they were having at that time.

For Hepworth and others there was an almost evangelical side to their practice, particularly in the promotion of a more integrated approach to an art that aimed to incorporate other disciplines such as architecture and design. During the Second World War Hepworth would become involved in keeping the modernist spirit alive, but more importantly she became part of a national conversation about the reconstruction of society – and among artists who were in dialogue with thinkers such as Karl Mannheim and Lewis Mumford. At the same time she remained highly sensitive to events in the wider world – for example, she joined the peace movement shortly after the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

Cutting from the Brazilian newspaper Última-Hora, 21 September 1959, showing Barbara Hepworth’s sculptures at the 5th São Paulo Biennial, 1959

Hepworth Photograph Collection © Bowness, Hepworth Estate, Acquis UH/Folhapress

In that spirit, in many ways it is her piece Single Form 1961–4, her largest and most significant public commission, made for the United Nations, that encapsulates Hepworth’s ideological and artistic aims. It is a theme that she started in the 1930s, and her revival of it indicates a recognition of the abiding relevance of her youthful ideals. Its subsequent erection in New York, in the shadow of the United Nations (an organisation that itself emerged out of 1930s ideals), was in essence the sculptural realisation of a faith in social co-operation and a sense of internationalism that had underpinned her art in the 1930s and subsequently.