Marlene Dumas in her Amsterdam studio with Andrea Büttner and Jennifer Higgie, November 2014, photographed by Rudolf Evenhuis

Jennifer Higgie Marlene, both you and Andrea are friends of the British artist Dick Jewell. He visited you soon after your arrival in Amsterdam…

Marlene Dumas We met by chance. Dick was from the Royal College of Art, and on the boat to Amsterdam he met my South African friend Michael Oblowitz, who was on his way to visit me in Haarlem, where I’d been accepted at the artists’ institute Ateliers 63. I had just arrived there, so didn’t know the place. I felt very lonely because I didn’t immediately connect to the Dutch people, so I just followed the two of them to the red light district and various strange bars.

Andrea Büttner It was interesting to read the timeline that you put together in the exhibition catalogue, which combines your own biography with important events of the day. For the year 1976, it says: ‘Dumas sees her first porn film, Deep Throat, in the cinema with artist friends Michael Oblowitz and Dick Jewell.’

MD I had never been in a real porn cinema. Dick was taking pictures while we were eating ice cream. I felt quite uncomfortable, especially as it was such a public place.

AB And you were with two men.

MD Yes, but they were just like kids. And Deep Throat did have some humour in it.

JH If you were so uncomfortable, why did you go on to make paintings about pornography?

MD Well, it didn’t just happen immediately. When Michael and I were at art school in Cape Town, life drawing was dying out. We were terribly bored with the models and life drawings. There are so many beautiful paintings of the naked person in Western art. These things stay with you, so when I arrived in Holland it wasn’t because there was this sexually liberal environment that I instantly made work about it, it was more that I’d been thinking about how the naked body is portrayed for a long time already. In the Netherlands pornographic imagery was common and often light-hearted, while in the fine arts sexuality and the nude had become almost extinct.

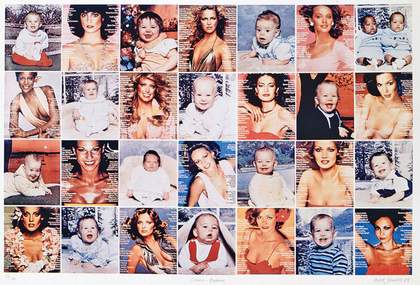

Dick Jewell

Cosmo Babies 1975

Photo lithograph, 650 x 900mm

© Dick Jewell, courtesy the artist

JH When I was walking around your exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum, I didn’t think about the women being pornographic. I just thought they’re revealing different aspects of being a woman. It’s like they’re all part of you.

MD That’s very nice of you to say so. When I was doing a lot of the erotic paintings, especially of the backsides, my mother said to me: ‘Oh, when are you going to do something else? Isn’t it a bit much.’ And I said to her, but once you have seen the front, shouldn’t one look at the backside too? She said: ‘Hmm, you’ve got a point.’ Also, two elderly blonde twins were on TV recently talking about why they became prostitutes and how friendly it was in the 1970s. It was different for me coming from South Africa, where everything was banned. The attitude was so much more tolerant in Holland.

JH Because it was normalised?

MD Yes. During my first year in Holland I didn’t really do much art, but I did learn from Dick. He became well known for his book Found Photos, published in 1977, which had a collection of photographs he had found abandoned in passport photo booths in English cities.

AB This is interesting when you think about the sort of image archiving that you do.

MD Well, I got that a bit from Dick. When I first saw his squat, he had piles of magazines and lots of images he had found in the streets. I made a drawing series, Fear of Babies, in 1986, based on one of his works called Cosmo Babies – in which he places images of babies next to cover models from Cosmopolitan magazine. He also introduced me to the films of Derek Jarman. It was at the time of punk. I saw Jubilee, and also his Sebastiane – my first gay erotic film experience.

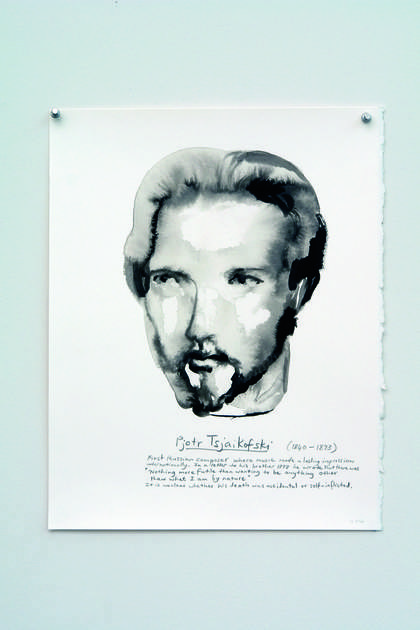

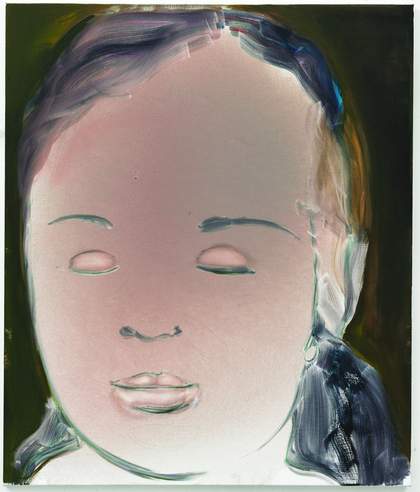

Marlene Dumas Pjotr Tsjaikofski from Great Men 2014–

© Marlene Dumas

JH Your 2014 series Great Men celebrates gay men in history who were persecuted for their sexuality, such as Alan Turing, Tchaikovsky and Tennessee Williams. These works were shown recently at the exhibition Manifesta in St Petersburg, and you have added a few more, including Jarman. What was the reaction, considering the new antigay laws in Russia?

MD One of the guys I’d put in there was a Russian television personality who came out.

AB And he was sacked, wasn’t he?

MD Yes. He sent me an email saying he was glad I had done the work and was so honoured to be among those other guys.

AB How does invention happen when you work from a photo or a film? When you start painting with an image that is already two-dimensional? I mean, how do you create new forms in a painting if you don’t have to translate three dimensions into two? And how important is the liquidity of paint for this development?

MD Very important. I understand it as referring to my way of using wet-on-wet materials, such as ink with lots of water, or at times quite diluted oil paint. Someone recently asked me a nice question: ‘If you like to work so fast, why don’t you use acrylic instead of oils that take longer to dry?’ I like my medium slow and my gestures fast. Acrylic dries too quickly. Then I can’t keep wiping it off. I like working on the floor, but these days I’ve got trouble with my knees, so I’ll have to change how I work so I can get back on my knees.

JH You mean getting down to paint low?

MD Yes, especially to do the watercolours. The first time I made the heads with watercolours so big was in 1994. But now I can’t sit very low on the floor (I think of Matisse with his long stick), so you have to adapt. My painting is a very physical act.

JH In a conversation with fellow artist Luc Tuymans you talked about the different scales of working. You wondered how he could work with such short brush movements, because you need to involve your whole body.

MD We move differently. So even if it doesn’t look like Jackson Pollock or Helen Frankenthaler, it is still a bit similar because I cannot get that skinlike feel if I sit at a table. It doesn’t flow in that way. I need a pictural idea to inspire me to start, but I need unexpected reactions from my materials to change that. Dick sometimes said that if there was a picture in a book I wanted to use, I should just buy the book. But he’s not a painter, you see, so he would have these drawers full of images, and then he would put them in a collage. I’m definitely not a director, in the way that he is. He’s more systematic than me. He showed me the differences and the similarities of poses across time and cultures. And how to look for them. The fashion model has her pose, the figure in art has its pose, and so has pornography…

JH You once said: ‘My art is situated between the pornographic tendency to reveal everything and the erotic inclination to hide what it is all about.’

MD Yeah, that is one of my older quotes, which I still like a lot. I’m filled with secrets, and there is a difference between me and, say, an artist such as Tracey Emin, who believes in having no secrets. It’s important to retain certain things. I don’t want to share it all, and I don’t want to say who inspired what. There are so many ways you can talk about certain works. I tell too much, anyway.

JH What is it about pornography that interests you – apart from the gestures, the idea of exposure?

MD To show or not to show. In art, that is the question. It is not that I want to see everybody without their clothes on. But it’s very stupid that in Hollywood love scenes the males always hide their sex.

JH You mean that the way love and sex is often depicted on film reveals a lot about culturally determined gender relations?

MD Yes! Gender relations. I think the reason I liked gay filmmakers (such as Warhol) a lot is because they could show a naked man just being naked. It goes back to the whole idea about how you treat the body. Most of the time pornography is very boring. Interesting porno, such as Deep Throat, has a bit of humour as well as a story.

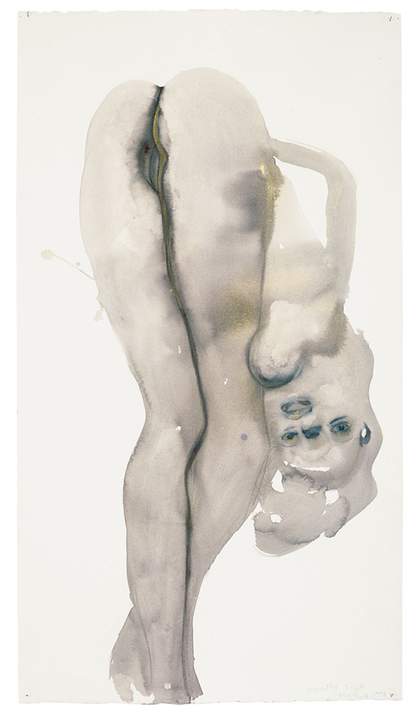

Marlene Dumas

Dorothy D-lite 1998

Ink and acrylic on paper, 1250 x 700mm

© Marlene Dumas, collection the artist

JH You’ve said that your pictures aren’t a mirror of reality, that they are the opposite – a way for you to explore something you don’t understand.

MD I don’t know if you actually do ‘understand’ more when you ‘see’ more. When I was looking at the porno ladies, I was specifically studying the positions they adopted to show everything at the same time. Sometimes it is incredible how they get it done. My work Dorothy D-lite 1998 is a good example of that. I also found them fascinating because I have never belonged to that group of women who look at their sexual parts. And I don’t know so well how I look anyway – I’m too stiff to bend like that!

JH Andrea, as well as being an artist, you’ve also done a PhD, the subject of which was the notion of shame.

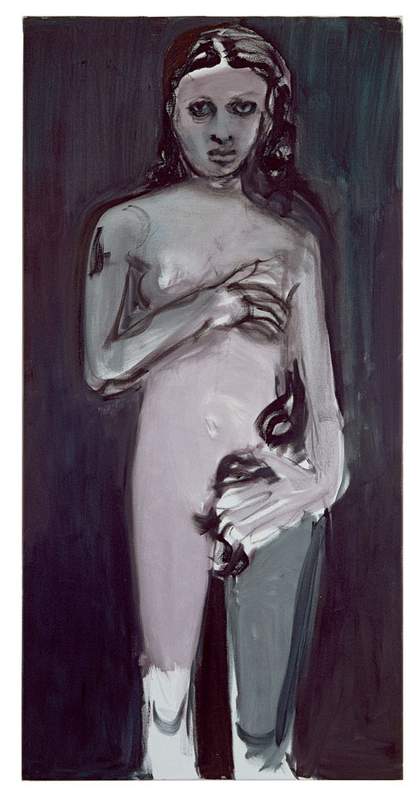

AB Yes. I was interested to see in the exhibition that there are a lot of depictions of shy people who cover themselves. These are mainly women, such as Magdalena (Venus) 1995, where she is covering her breasts. Also, I love Confession 1993. To me, this speaks about you being full of secrets and not showing everything, and how it is actually impossible that paintings show everything.

MD Certain information is not in there. I’ve always been interested in what can be read into a work. It’s not that I want to stop all the interpretations, but I would say to people they must make a distinction between what is actually visible and what they think is there.

AB There’s a quote by the artist Elke Krystufek that I love very much: ‘Naked language can’t be spoken’. Represented nakedness is always covered in language, in modes of representation, it’s always painting. So you are interested in exposure or nakedness, but in the end art always fails to be naked.

MD I like that. I remember reading something that Okwui Enwezor quoted in his text Haptic Visions about Steve McQueen: ‘The visual is essentially pornographic.’ As if just by looking at things intensely you almost inevitably enter the realm of the pornographic. I understand his point, but I think that’s a bit too much. And I’m not Roman Catholic, but I always found it intriguing that the priest who listens cannot be seen, and may not talk about what he has heard later. I can relate that to other states of being, although it’s not directly my thing – I’ve never confessed in the confessional box, for example.

AB But it’s interesting how it relates to painting. This veil in front of the confessional box is the canvas. So the canvas also covers at the same time as it shows something.

MD I agree. For example, the painting Fingers from 1999 is always described by writers as if everything is depicted, but if you look at it closely, there are no genitals there. That little painting exposes nothing really. It is quite abstract. Very gestural. It is all about suggestion. It is not a realistically painted painting. It does not actually resemble its photographic source material at all.

Marlene Dumas

Magdelena (Venus) 1995

Oil on canvas, 2000 x 2000mm

© Marlene Dumas, private collection, Belgium

AB I’m wondering if nakedness is also about an attitude, beyond questions of the iconography of the pornographic? There’s a nakedness in the eyes; in the vulnerability of people looking at you. Do you think you achieve the kind of nakedness you want to paint?

MD I don’t know actually. I agree that nakedness is also about an attitude, and I have said before that I don’t want the nude, I want the naked. But I do know with the descriptions of things, as with the Magdalena paintings, that I was deliberately not looking for seduction, but rather for confrontation, and for a long time that was also the case with my other depictions of figures. Maybe I thought that confrontation was closer to nakedness than seduction. But with my light works in the Iate 1990s, I did want to see if I could make them erotic. Snowwhite and the Broken Arm and Snowwhite in the Wrong Story, both from 1988, are not at all about eroticism, it’s more about the weight of the body. The spirit lifts you up, while the body pulls you down type of thing. But with good eroticism, just for a while at least, all of this becomes nonsense… Take the striptease project I did with Anton Corbijn. I don’t think I succeeded in portraying the essence of stripping. Striptease is a dying art, because it is all about movement and timing, and no one wants to take the time anymore. The girls, they just want to get it over and done with and almost don’t even do a tease. They get rid of their clothes much too quickly. It used to take so long to undress that when the last bit of clothing went, the stripper left the stage too. The tease is the tension. Revealing by slow motion. Strippers move. Paintings are still. All paintings are still lives.

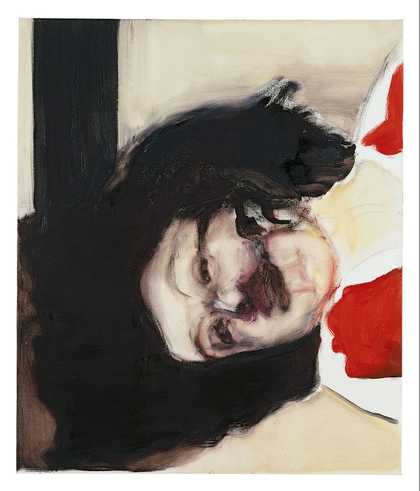

Marlene Dumas

Helena’s Dream 2008

© Marlene Dumas

Photo: Peter Cox

JH In many of your paintings you depict people with their eyes closed – they might be dead or sleeping, crying or even bandaged. It’s often ambiguous.

MD Apart from emotional reasons, there are also formal ones for moving from a frontal vertical gaze as a means of making eye contact with your public, which I have used for a long time, to a more horizontal view of a figure that does not return your gaze. It is an illusion that these eyes look at you anyway. The dead or asleep ones give you less the illusion that they are real people. From 1976 to 1984 I didn’t really paint the figure, and then I couldn’t paint without it. The Eyes of the Night Creatures exhibition had all these big heads with eyes questioning you. I used myself and my boyfriends for the couples. I was happy with their scale making them more abstract, because the portrait was such a reactionary thing. Later I thought maybe these paintings work only because of the eyes looking at you, so what if I use the body without the face? Hence works such as 1988’s Waiting (for Meaning) and Losing her Meaning. And then much later I returned to the face, but now with its eyes closed. The portraits became more ‘introverted’.

AB What do you think about this notion of figurative painting being considered reactionary?

MD Oh, I don’t worry about it anymore, although I did then. There is a lot of terrible figurative painting around now. It’s fashionable and considered more political in general. When I started to do the figures I was a bit ashamed, because in a sense I thought: ‘Is this all I can do?’ But I have seen artists rejected by galleries on the grounds that they are now more interested in those ‘who do political work’. I think that is so horrible.

Marlene Dumas: Image as Burden

© Tate photography

JH Do you think your work is political?

MD Yeah, but, you see, it’s just like the word feminist. I saw my work being called that for a long time, but I didn’t use it because I was never part of any group. Then it’s used in a different way, and I don’t mind sometimes. But is my work political? In South Africa I didn’t know how to make something about the politics: do you paint someone killing someone? Then I thought could it be possible at least to make a work that someone you totally don’t like won’t ever want to buy or exhibit? That would be fantastic. For a little while I thought like that about the series Black Drawings 1991–2. There comes a time when you feel you can take on a certain subject.

JH You said in one interview that an American institution’s wall label describing Black Drawings as a criticism of apartheid was misleading – that your intention was more complicated than that.

MD It was too simple a definition. It took me a long time to know how to speak about those works, because I can always see the criticism coming. But I realised that (white) Americans and the Dutch, in particular, when they insist on saying it’s about apartheid, it’s as if they are not open to their own feelings when they see a group of black faces and all the whites are excluded. So Black Drawings is a political work in the sense you cannot look at it – or you can almost not look at it – because it is still an issue. But everyone comes to the work with their own views and prejudices. For example, a Dutch girl, who was black, said to me that she liked it so much because she sees so few images of black people in museums.

Marlene Dumas

The Image as Burden 1993

Private collection © Marlene Dumas

AB What’s the difference when I look at a portrait of Osama bin Laden and one of a model or an anonymous person? You instill a kind of empathy in the viewer for these people. How does this relate to the political narrative?

MD Again, that is something I don’t quite know how to articulate. I do work with these problems, but I don’t always know what I think about them. For example, I painted a portrait of Mohammed, who killed the Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh on the streets of Amsterdam in 2004. I have always defended why I did it. I used his face as a way of portraying the wider subject of local terrorism, rather than producing a whole war scene. It was not done in order to glorify him. But I have to admit I sometimes want to destroy that painting because I feel a bit sick every time I look at it. Maybe because he killed a specific man that I liked, although I didn’t know him personally, or just because I really dislike his facial expression. However, I don’t feel the same about the portrait of Osama. In London several years ago I showed it in an exhibition called Forsaken, which also included pictures of Jesus on the cross. Interestingly, it was the Jesus works that got me into a lot of trouble.

JH In what sense, trouble?

MD Lots of people, even Jolie who works with me (and is not religious), said why are you painting Jesus on the cross? The subject seemed to bother them. But in comparison with the other portraits, there is no ‘real’ Jesus face; there is no original to use as a model.

AB And it’s about art history, not about Jesus.

MD Most art people don’t want to think they have a religious symbol in their house, because they are secular.

AB I’m interested in this question of religious iconography being a taboo.

MD That was a total surprise, because when I have used images of babies in my work, for example, quite a few women have said: ‘I’m so pleased you paint babies!’ I like Malevich’s paintings of crosses, but I always need the figure somehow (I would love to be an abstract artist), so I tried to make Jesus so much part of the cross that he almost becomes that cross. But going back to Osama, I chose a very well-known image of him. And when the Stedelijk bought that small painting and put it on display, some said I made him more feminine and soft – but I didn’t, he already had that quality.

JH He had a seemingly gentle, rather beautiful face, which somehow made his actions even more horrifying.

MD Yes. I found him attractive too. And also that media picture was used so often that I questioned whether it was becoming positive propaganda. I showed the painting I’ve made of his son, called Son of, next to his portrait for the first time in Amsterdam. I thought that was so interesting on a psychological level to see how people read images. And how what you hang next to a work changes that work. Now people saw in the same painting a loving father.

JH In terms of people in the news, it’s as if you’re taking exhausted images that have been seen and reproduced so many times, and then trying to find something real in them again.

MD Maybe that is part of the challenge…

AB When I look at your portraits I think these photos spoke to you and looked at you, and you then give them to me. Now they speak to me and look at me, but there is a sense of anonymity. I am indifferent to who the person is. In a way, you anonymise these famous people, and I think with mass murderers that’s problematic, because it’s a problematic relation to history. In the experience of viewing these portraits, the narrative has been removed from something that’s actually very narrative. These gazes sit oddly with the narrative.

MD But this relates back to your question about political… because sometimes I think I am amoral, and I think painting should be amoral.

AB I think it’s more a question of politics and ethics.

MD Well, as you just explained it, it doesn’t sound like it! But I mean yes, in a sense, although I am not really taking responsibility for the bad deeds of these characters.

AB But you create a kind of empathy around them…

MD Yeah, love your enemy. I don’t like revenge. I understand it very well, but I don’t really like the idea of making your enemy suffer.

Marlene Dumas

The Widow 2013

Private Collection

© Marlene Dumas

JH You said once that when you were an art student in South Africa you felt ‘entirely inadequate, ill-equipped to address the political system of apartheid in my work’. Does that still hold true? How does anyone understand or address the complexities of today in a single image?

MD A single image is often not enough, therefore you need to see an exhibition. Or at least a group of works together. Relationships ‘between’ are important. I look at things that scare me, and perhaps not all my work is like that, but a good example is the painting Dead Girl 2002. This relates to giving source material too much attention, which is also something that I’m worried about. I used to not mind showing where my images come from. But the start is not the finish. The problem is if I call it Dead Girl, and then tell this story about the source of the image, the emphasis shifts more to the story than the painting. With Dead Girl, I didn’t know that she was Palestinian when I first saw the picture. I just saw this young girl shot dead who had hijacked a plane in 1977. In those days I cut the image out without referencing where it was from or when. Now I do want to know where it comes from. I looked for that image on the internet, but couldn’t find it. A similar thing happened with the source photo I used for two paintings, The Widow 2013, that show Pauline Lumumba, bare-breasted soon after the murder of her husband Patrice, the former prime minister of the Republic of Congo, in 1961. I couldn’t find the original on the internet… In these paintings I didn’t try to make my main character anonymous. I tried almost to give the photograph more – how can I say? – credit. I stayed very close to the original framing or cropping of the picture, and didn’t render it so that the photo disappeared in the paint. Amazingly, the guy who took it, and had not seen it again for all this time (he sold it to UPI in 1961), Ed van Kan, got in touch with me. He is a Dutchman, now in his 80s. I told him that, as a student in South Africa, the autobiography of Simone de Beauvoir was very important to me, and recently I had gone to look at this book again and found that I had underlined a section where she writes about the importance of that photograph of Pauline Lumumba all those years ago, long before I made The Widow.

Marlene Dumas

Dead Girl 2002

Oil on canvas, 1300 x 1100mm

© Marlene Dumas, courtesy Los Angeles Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Buddy Taub Foundation, Jill and Dennis Roach, Directors

JH Your painting The Wall 2009, showing Israeli men standing near the partition wall, seems to establish a complex narrative about right and wrong…

MD I just hope that my painter’s ‘talk’ is similar to that of the painting’s ‘walk’. I am a bit uncomfortable with what is sometimes relevant and what is not. When I made Dead Girl it was a time when my teenage daughter was doing dangerous things, and I was very scared for her. So, actually, it was also a painting of my own fear, because this girl was so young and vulnerable. An extremely sad image. Sometimes for me there’s also this voodoo aspect … and then I get frightened. There’s the right and wrong of your own intentions, and the consequences. I wanted to paint it almost as a call for protection. And then I thought maybe if I paint that, it will bring on the bad luck.

JH Do you know what your next paintings will be?

MD No, not at all. There must be an emotional element to get me to make that step, and then when I do make it, I get into it and other associations follow. Like the Against The Wall paintings. They are about an unjust political system, but also I think I myself feel a little bit against the wall in another sense of the word…

JH How was it seeing 40 years of work? Was it a very emotional experience for you?

MD At first I thought it was terrible to see them all, because it was too soon after this retrospective in America where I didn’t make many new works. But when I calmed down and looked at myself more as a third person again, I was surprised. I realised that I didn’t know these works very well at all.