Raphael Hefti

Lycopodium 2011

Photogram on paper, 1060 x 1800mm

© Raphael Hefti, courtesy Ancient and Modern, London

A photogram is not a photograph, not really. Sure, it is usually discussed as a subset of photography, and it was born around the same time, from similar chemistry, but is practically and conceptually only remotely related. It is no more a photograph than a photocopy, an X-ray or a digital scan. Photography typically uses lenses to project light on to film, and then on to paper, in order to render an objective representation of a scene or object. It changed the world because of its reproducibility, and because of its capacity for vivid mimesis.

A photogram, on the other hand, is a 1:1 scale negative record of a shadow. It is unique and unpredictable. Photographs tell sweeping, barefaced lies; photograms tell the truth, but only a thin slice of it. Genealogically, photograms have more in common with print-making, or even with the world’s oldest known paintings: outlines of hands silhouetted by pigment blown on to cave walls in Indonesia and northern Spain, dating from around 40,000 BCE.

Is this why photograms, and other cameraless photographic techniques, currently proliferate in contemporary art? The ocean of images that surges and swells around us is mainly photographic; we are awash with manipulated half-truths and shameless fictions. Smartphones allow you to edit and enhance images seconds after you shoot them. We are all of us eloquent in the language of photography, from the shallow depth of field of the expensive SLR lens and the all-over focus of the large-format Hasselblad to the vignetted corners of yellowing Polaroid snaps. Even children can interpret the subtly different meanings of Instagram’s palette of 20 filters.

Walead Beshty

Black Curl (CMY/Five Magnet: Irvine, California, March 26th 2010, Fujicolor Crystal Archive Super Type C, Em. No. 165-021, 05110) 2011

Colour photographic paper, 1307 x 2702mm

© Walead Beshty, courtesy the artist and Regen Projects

Nathaniel Mellors recently embarked on a series of colourful and inexpert photograms of his own sculptures in order to contemplate, as he put it, ‘a return to the cave’. They were exposed in complete darkness and developed in his friend’s bathtub. Sam Falls has left lengths of hand-dyed fabric out in the sun with objects including tyres and planks laid on them, making basic photograms with exposures weeks- or months-long. Falls has also used coloured light to make luminograms – close cousins of the photogram, records not of shadows but of light itself. In pictures such as Untitled (PP 14) 2011 he emphasises this painterly process by applying acrylic to match the printed colour.

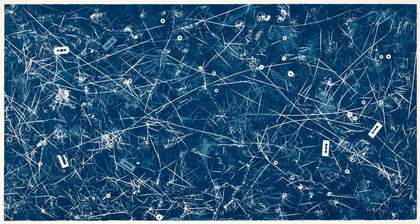

Liz Deschenes and Wolfgang Tillmans have made luminograms, respectively, of moonlight and fairy lights piled directly on photographic paper. Along with influential figures including James Welling and Walead Beshty, they use cameraless processes to reach for a kind of self-reflexive formalism. Beshty and Christian Marclay have both used the old cyanotype process, Marclay in prints of unspooled cassette tapes (another obsolete technology) and Beshty in a recent installation that archived objects from his studio as cyanotypes on chemically treated scraps of paper and card.

Nathaniel Mellors

Venus of Truson (Prehistoric, Photogrammic Originals) 2011

510 x 610mm

© Nathaniel Mellors, courtesy the artist and Matt’s Gallery, London

Some people contend that photograms came into existence over a century before photographs. The German physicist Johann Heinrich Schulze noted the darkening effect that sunlight had on a jar of silver nitrate solution in 1727. He cut out a paper stencil of letters, and amazed his colleagues by printing a word on to a piece of gypsum soaked in the solution. (It is sadly not recorded what he wrote.) This differed from subsequent photograms only in its impermanence.

William Henry Fox Talbot’s first ‘photogenic drawings’, as he called them, made during the ‘brilliant summer’ of 1835 by placing objects on paper photosensitised with salt and silver nitrate solutions, were mostly botanical records of plants and lichens. (Talbot and his pioneering colleagues were scientists first, and picture-makers second.) Lace and frilly fabric cast appealing shadows too. Although the term was not used until 1859, these were photograms.

Talbot unveiled his refined ‘calotype’ process in 1841. One year later, another gentleman scientist, Sir John Herschel, announced a competing invention: the cyanotype, which used potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate. Cyanotypes are today better known as blueprints, and are noted for their permanence. Though the technique has a beautiful simplicity, it is not as sensitive as silver nitrate so is useless for incamera photography, only capable of generating photograms when exposed to light for long periods.

Sam Falls

Untitled (PP 14) 2011

Acrylic on C-type print, 762 x 1016mm

© Sam Falls, courtesy China Art Objects, Los Angeles

As with Talbot’s photogenic drawings, cyanotypes were primarily used for botanical purposes. Their most famous exponent is Anna Atkins, who was a friend of both Talbot and Herschel, and wasted no time in adopting both men’s inventions. Her self-published Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions of 1843 is widely considered the first photobook.

As photographic technology advanced through the 19th century, the primitive photogram lay dormant, little used by artists until the First World War simultaneously shattered Europe’s faith in the mechanics of the modern world and intensified the pursuit of new kinds of art. Dada embodied this contradiction absolutely: the movement was at once avant-garde and primordial, progressive and regressive. The painter Christian Schad moved to Zurich in 1915, where he associated with dada artists Hugo Ball and Hans Arp. Inspired by Talbot’s photogenic drawings, between 1918 and 1919 he produced photograms that he called Schadographs. (Was the pun ‘shadow-graphs’ intentional for the German-speaking artist?) Instead of flowers and leaves, he arranged torn and crumpled paper, snippets of newsprint, fabric and hairballs – the grimy jetsam of modern city life.

László Moholy-Nagy

Photogram No.II 1925

Galerie Berinson, Berlin/ Ubu Gallery, New York

Tristan Tzara, the leader of Paris dada, acquired examples of Schad’s experiments and probably showed them to his friend Man Ray, who moved to Paris in 1921. The latter never acknowledged the influence, but produced his own photograms, which he branded Rayographs, in 1922. Man Ray’s plagiarism notwithstanding, there is no question that he moved the genre forward from Schad’s uncertain efforts. His Rayographs were produced not in daylight but in the darkroom, and his punchy compositions used graphically distinct forms, mainly massproduced consumer goods. They were published in Vanity Fair, and as product advertisements in Harper’s. Their material uniqueness – which renders any photogram more akin to a drawing than a photograph – may seem at odds with the way they lent themselves to reproducibility.

This commercially inclined mix of technology, science and art also appealed to László Moholy-Nagy, who began experimenting with photograms in his Berlin studio in 1922. Unlike Man Ray, he employed less easily identifiable objects in his photograms, and used translucent or diaphanous materials to scatter light and imply depth.

In 1930 he hired fellow Hungarian György Kepes as his assistant; they both fled Nazi Germany in the mid-1930s and ended up in Chicago, where Moholy-Nagy established the New Bauhaus School of Design in 1937, appointing Kepes head of the poetically named department of colour and light. Kepes did not consider himself a photographer – he was a painter, a designer and a filmmaker – but the photograms that he made at the New Bauhaus are among the field’s most revered. Though aesthetically refined, each of his photograms seems like an experiment with prisms, water droplets and explosions of light. (‘I have tried to invent anything and I have never made an experiment,’ crowed Man Ray, by contrast.)

The New Bauhaus survived only until Moholy- Nagy’s death in 1946, but for under a decade it witnessed intensely inventive experimentation in all kinds of photographic techniques, not just photograms. Henry Holmes Smith, Arthur Siegel, Nathan Lerner, Lois Field and Max Pritikin were all either students or on the faculty at the school. It was Siegel’s work that inspired Thomas Ruff to make a series of giant digital photograms – prints using virtual objects, built with 3D imaging software, as light masks over a virtual sheet of paper.

Christian Marclay

Allover (Genesis, Travis Tritt and others) 2008

Cyanotype, 1308 x 2483mm

© Christian Marclay, courtesy Museum of Modern Art, New York/SCALA Archives, acquired through the generosity of Steven A and Alexandra M Cohen

Ruff’s photograms feel lifeless and chilly next to the work of artists such as Susan Derges, Jochen Lempert or Adam Fuss, whose pictures are energised by the knowledge that they have actually come into contact with the objects they represent, whether running river water, tiny frogs, rotting sunflowers, or splayed animal intestines. Like Lempert and Fuss, the young Swiss artist Raphael Hefti studied science before turning to art. In a darkroom, Hefti spreads combustible moss spores on photographic paper in his series Lycopodium, begun in 2010 and ongoing, which expose the paper when he sets them alight.

A similar alchemical sorcery is implied in certain photograms of the German photographer Floris Neusüss. After experimenting with body prints in the late 1960s and 1970s, in 1984 Neusüss hit upon a technique he called his ‘Nachtbildern’, or ‘Night Pictures’. He would take pieces of photo paper into his garden during a nocturnal thunderstorm, and allow the lightning to expose impressions of grass, leaves and branches on to them. Around the same time, he produced the dinner table-sized picture Nachtmahl für Robert Heinecken, Kassel 1983, a homage to the gastronomic photograms of his friend, the Californian ‘para-photographer’ (as he liked to describe himself). Heinecken used the photogram process throughout his career to copy magazine images (usually pin-up girls or advertisements), but in 1983 he made a series of ‘Foodgrams’ – meals served on colour photographic paper.

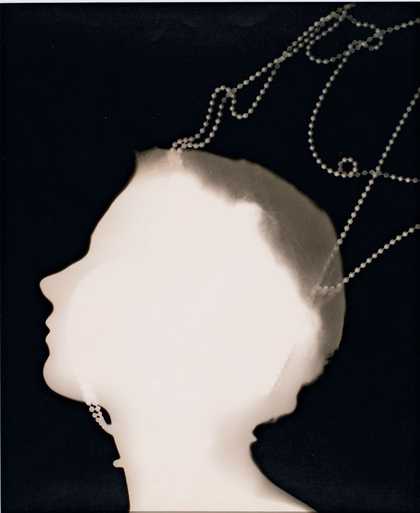

Len Lye

Anne Lye 1947

Photogram - gelatin silver print, 405 x 335mm

© Len Lye Foundation Collection and Archives and Govett-Brewster Art Gallery

The indexical thrill of the photogram lends itself, albeit impractically, to portraiture. The New Zealander Len Lye, known for his abstract films and kinetic sculptures, made a number of photograms in the 1930s and 1940s, when he was living in London. He persuaded notable subjects including Georgia O’Keeffe, Joan Miró and Le Corbusier to lie on the ground and press the sides of their faces to a sheet of photographic paper, sometimes augmented by decorative elements. The contemporary artist Farrah Karapetian also orchestrates photograms with human figures, although in her tableaux – featuring soldiers or riot police, for instance, and inevitably 1:1 scale – the contrivance of the drama is revealed in the painstaking methods that produced it, which include not only stock-still models but also handmade props.

Farrah Karapetian

Muscle Memory 2013

Chromogenic photograms from performance, three panels, each 2743 x 889mm

© Farrah Karapetian, courtesy Von Lintel Gallery, Los Angeles;

Jason Lazarus

Study #13, the year of Heinecken’s birth #2 (19y, 31m at F16, 6 sec, dodged for half of exposure) from the series Heinecken Studies 2010

C-type print, 508 x 610mm

© Jason Lazarus, courtesy the artist

The last word ought to go to Jason Lazarus, who found a more convenient way to capture the human body as a photogram. He discovered that when Robert Heinecken was cremated, in 2006, his ashes were divided into salt shakers and distributed among his friends and colleagues. Lazarus’s Heinecken Studies 2010 depict Heinecken’s remains as galactic pinpoints of light on coloured grounds. They elucidate their medium’s noblest qualities: wacky science-lab experimentalism, auratic power, brass-tacks simplicity, absurdist humour and a reverence towards the chemical wonders of analogue photography.