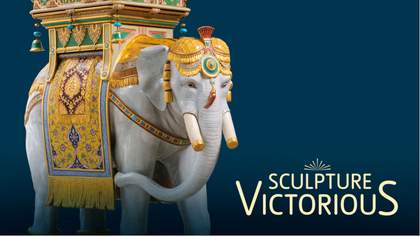

Model of Queen Victoria's statue in George Frampton's studio (before 1902)

Courtesy Henry Moore Archive

A new race of sculptors has arisen in England, who possess in a remarkable degree the qualities in which their predecessors were deficient.

This confident judgement of the jurors of the Great Exhibition in 1851 reflected a widely held perception that Victoria’s reign was a golden age for British sculpture. The country had a monarch and a consort who encouraged sculptors, and their rule inspired sculptural tributes by institutions and cities across the nation and the empire. The state, long a bystander in the patronage of the arts, commissioned a range of sculpture and decoration to ornament the new Houses of Parliament, with the express intention of supporting the national school. For Britain’s many gifted sculptors there had never been so many opportunities for innovation and display.

This was a period in which fine art sculpture was created using new scientific techniques, and was considered an indispensable element of the best silver work, furniture and ceramics. Coupled with scholarship of antiquity and knowledge of the immediate past, the environment of invention seems, indeed, to have created great sculptors.

Frederic, Lord Leighton

An Athlete Wrestling with a Python 1877

Bronze, 984 x 1099mm

Photograph © Tate Photography, Tate collection

Paul Comolera

Peacock 1873

Tin-glazed earthware, majolica, 1828mm high

Courtesy National Museums, Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery

Some of the works that emerged from this crucible are familiar to Tate visitors, such as Frederic, Lord Leighton’s iconic An Athlete Wrestling with a Python 1877, a muscular but distinctive homage to the ancient Laocoön. Yet the era abounds with lesser-known tales of sculptural achievement. Thomas Wallis had produced intricate and naturalistic wood carvings of plants and birds in the 1840s in his native town of Louth, but then the ‘Lincolnshire Grinling Gibbons’ (a reference to the celebrated 17th-century carver) provoked a ‘furore of admiration’ in London through his technique of painstakingly carving his works from a single block of lime wood, including the finely whittled pieces of string in Partridges and Ivy 1871. He thus demonstrated how far his method had exceeded the skills of the great Gibbons, who built up his sculpture in sections slotted together.

The relationship between sculptors and manufacturers often produced remarkable and beautiful works of art. John Bell worked with the Coalbrookdale Iron Foundry in Shropshire to show how iron, previously considered too rigid a material for fine sculpture, could be used to produce great and small versions of his famous The Eagle Slayer of 1851, while HH Armstead applied his sculptural prowess to create showpiece works for silversmiths and jewellers. Paul Colomera’s breathtaking majolica Peacock 1873 was commissioned by Minton’s, the ceramics manufacturer. Modelled from life, it was used to demonstrate the firm’s vivid lead-glazing, and was unusually hardy, as witnessed when a version survived a shipwreck en route to the 1879 Melbourne International Exhibition.

George Frampton

Dame Alice Owen 1897

© Dame Alice Owen's School

The Birmingham firm of Elkington & Co transformed sculpture through its patented forms of electroplating and electroforming in the 1840s, in which an object, or a mould, could be dipped in a metals solution which was gradually decomposed using an electrical current, leaving a thin shell of gold, silver or copper on the surface. Electrodeposition was cheaper than traditional casting, and this combination of innovation and thrift won Elkingtons prestigious commissions. In addition to historicising statues and scenes from British history for the chamber of the House of Lords, it made a series of electroformed reproductions of royal monuments for the National Portrait Gallery in the 1870s, the originals of which were causing concern to preservationists due to their weathering and neglect. The firm’s copy of Maximilian Colt’s original stone carving of Queen Elizabeth I in Westminster Abbey is one of the finest, formed in copper from a plaster cast made from the original monument.

William Reynolds-Stephens

A Royal Game 1906-11

Electrotyped bronze and wood, stone, abalone and glass, 2407 x 2330 x 978mm

photograph © Tate Photography, Tate collection

Sculptors frequently contributed to the inventiveness of the time. Francis Chantrey (1781–1841) developed a new pointing machine for transferring sculptural dimensions from model to marble, aided James Watt in the creation of a machine for carving small-scale sculpture and built his own foundry for bronze. At the close of the Victorian period William Reynolds-Stephens devised electrodepositing techniques to use within his own studio, as he felt sculptors should ‘be fully acquainted with all the processes of production’. His A Royal Game 1906–11, one of the early purchases made for Tate with the Chantrey Bequest, is fashioned from electroformed copper, carved wood, decorative semi-precious stones and a host of metallic coatings. Representing Philip II of Spain playing chess with Queen Elizabeth – with ships for pieces – it was an allegory of the buildup of naval tension with Germany in the first decade of the 20th century. Although completed a couple of years after the death of Queen Victoria, it perhaps best represents the apogee of the formal and technical innovation that marked this age of sculpture, and the unrivalled group of sculptors it produced. Sculpture victorious, indeed.