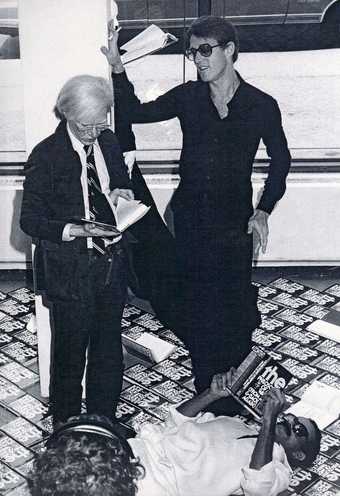

Andy Warhol with Halston in a window display for his book The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again), 1975

Courtesy Lucy Mulroney

Andy Warhol once said: ‘I want to be a machine.’ If I were to imagine what kind of machine he had in mind, I’d say a printing press. He was always publishing something. Before he began making silkscreen paintings, he self-published illustrated books that he produced collaboratively with friends and lovers during the 1950s. The first was called Love is a Pink Cake. It paired line drawings with poems about ill-fated couples, including: ‘Chopin some say loved George Sand, / He tried but once to hold her hand, / For once was enough; this lesson he learned / If your girl smokes cigars you’re apt to be burned.’ Over the next eight years, he published another seven books and created manuscripts for many more. Campy, coy and playfully subversive, they were also great self-promotion.

Throughout the 1960s Warhol travelled in avant-garde circles, regularly attending basement film screenings and poetry readings, and contributing cover art to several little magazines. Frequently, he used these covers to promote his own films. For example, a series of close-ups from Sleep were reproduced on the cover of Film Culture; two frames from Kiss comprised the cover of Kulchur; and a scene from Couch graced the cover of Fuck You: a Magazine of the Arts. It was during this period that he also got his first tape recorder, which he used to ‘write’ a novel based on a day-in-the-life of his friend Ondine, an amphetamine addict known for his feverish style of elocution. After he finished taping Ondine, Warhol hired some high school girls to transcribe the cassettes and pitched the book to Grove Press. Grove agreed to publish it, but the manuscript sat forgotten (or, perhaps, consciously avoided) in the company’s editorial files.

Installation of Transmitting Andy Warhol at Tate Liverpool

© Tate Photography

Meanwhile, Warhol was working on a book with Random House. It was released in 1967 in time for the holiday shopping season as a hip gift book under the title Andy Warhol’s Index (book), a pun on the Catholic Church’s index of forbidden works and authors. It came in a hologram cover with Campbell’s Tomato Juice endpapers, several 3D pop-ups, a flexi-disc bearing Lou Reed’s portrait and a stream of uncaptioned black-and-white photos of Factory superstars. As the editors were putting the final touches to the book, Kasper König, the pre-eminent curator of contemporary art, then only 24 years old, was in New York compiling the exhibition catalogue for Warhol’s retrospective at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. The book, a beautiful Warholian document in four sections – a selection of real and fictitious quotes by and about the artist, a series of reproductions of his work made by König on the Castelli Gallery copy machine and two sequences of photographs by Billy Name and Stephen Shore – was the size of a telephone book, was printed on newsprint by the printer of a daily Swedish newspaper, and came wrapped in fluorescent flowers.

Around the time of the retrospective in Sweden, a young editor by the name of Arnold Leo came across Warhol’s book proposal languishing in the files at Grove Press, and he asked his boss if he could take on the project. The manuscript was a mess, and he realised that substantial editing would be necessary to make it readable. He arranged a meeting with Warhol and Billy Name, who told him they didn’t want the novel edited. ‘ “Isn’t that like what makes it real,” they said. “The typists’ mistakes are all part of the process of creating a novel. It wasn’t just a recording, but also the typing; and the manuscript should be reproduced the way it is.” ’ So Arnold carefully formatted the text and gave consistency to the punctuation, while leaving most of the typists’ errors intact so that the book still read like an unedited transcript. They titled it simply, a. The critics trashed it, and Grove and Warhol appropriated the bad reviews for the advertising campaign for the paperback: ‘They laughed when he stepped up to the easel… and when he picked up a camera… and now that he’s written a novel? Nobody’s laughing; they’re all screaming! “Vile, disgusting, dull, filthy” – the voices cry. The New York Times called a, among other things, “the all-time low in pornography”. Will Andy Warhol again have the last laugh? See for yourself, pick up a copy of a, a novel by Andy Warhol.’

Installation of Transmitting Andy Warhol at Tate Liverpool

© Tate Photography

Installation of Transmitting Andy Warhol at Tate Liverpool

© Tate Photography

After a, Warhol planned to do a book every five years, with b as the first sequel. This never materialised, but in 1975 he published his book of philosophy, THE. Culled from taped conversations with writer Bob Colacello, his assistant Pat Hackett and his best friend Brigid Berlin, THE, or The Philosophy of Andy Warhol as it is commonly known, takes the form of a conversation: ‘From A to B and Back Again’, with A standing for Andy and B for Bob and Brigid. As critic Peter Plagens complained: ‘The book reads like it’s straight off the dictaphone, transcribed in Lindy ballpoint drone, as though by an overweight 15-year-old White Plains school girl.’ None the less, it’s Warhol’s most-quoted book, and has never gone out of print.

The last thing he published before his death in 1987 was a photobook entitled America. Following in the footsteps of Walker Evans and Robert Frank, it is premised on the survey of the nation by the photographer who has witnessed its social climate from political rallies to lunch counters. Warhol’s America not only perpetuated the cliché of the US road trip, it necessitated that he go on one. The promotional tour for the book lasted three months and included radio appearances, autographing sessions, champagne receptions and even a recording session for an in-flight audio magazine. It was disastrous from the start. At his second book signing, a young woman yanked the wig off his head and tossed it over the balcony to an accomplice who ran out of the store, leaving Warhol at the autographing table, humiliated and exposed. The staff asked if he wanted to stop, but there were people still waiting in line. So like the machine he said he wanted to be, Warhol pulled the hood of his coat over his head and just kept signing. © the author