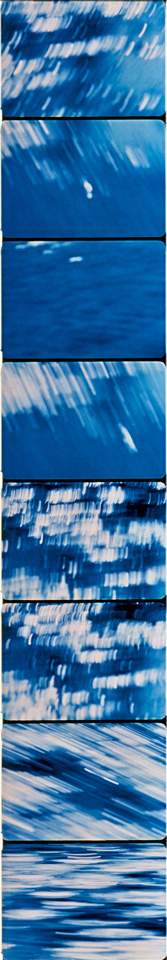

Stan Brakhage

stills from The God of Day Had Gone Down Upon Him 2000

16mm film, 50min, colour, silent

© Estate of Stan Brakhage, courtesy Fred Camper

Towards the end of his life, the pioneer of American visionary film Stan Brakhage made the silent 16mm The God of Day Had Gone Down Upon Him 2000. This work relishes varied oceanic light, dramatised by rhythmic camera movements and edits, attention to visual textures and forms, and their consequent moods. It is a typically Turnerian subject: the essence of his late works, Lawrence Gowing observed, might be gathered from the compound infinite meanings he gave to water.

Earlier, in 1974, Brakhage made The Text of Light by filming objects through the prismatic filter of a crystal ashtray. Never is the ashtray revealed in its totality. The film’s image is seared by layered textures of shattered light and colour, caught in a feedback loop between the camera’s optics and the filter before it. In The Text of Light Turner’s influence is felt in the experimental use of colour, and is similarly visionary in the way it collapses naturalistic pictorial space. Brakhage first saw Turner’s paintings in New York in the 1950s, would reference them in his lectures, and knew intimately which works hung where in London museums. ‘Stan,’ as Marilyn Brakhage told Tate Etc. recently, ‘often spoke publicly about Turner’s importance to him.’

Turner also influenced in particular a generation of British experimental landscape filmmakers, among them Chris Welsby, William Raban and John Woodman. Known for their ‘structural cinema’, their works focused on film’s material substance – light, time and process – to create what they saw as a new form of aesthetic that was free of symbolism or narrative. Even ‘mistakes’ such as flare, scratching, slippage and double exposure would be incorporated (one thinks here of Turner’s ‘mistakes’: spitting on the canvas, overpainting ‘finished’ works on varnishing day).

Sensuality of landscape imagery became a primary vehicle to assert the illusionism of cinema, while simultaneously asserting the material nature of the representational process which sustained the illusionism. Raban’s View 1970, for example, alternated shooting speeds to introduce rhythm into the landscape. Colours of This Time 1972 used long exposures to change the colour of sunlight (in MM 2002 the camera stares unblinkingly into the sun). River Yar 1971–2, made with Welsby, presents, in time-lapse, two views of the river at set points around the autumn and spring equinoxes and alludes to the passage of the moon around the earth – signalled by the change in tides – and the passage of the earth around the sun – the light at different times of year. ‘With both Constable and Turner,’ Raban has commented, ‘I was interested that their work preceded the French naturalists like Monet.’

John Smith

still from Horizon (Five Pounds a Belgian) 2012

HD video, seamless loop (cycle 18min), colour, sound

© John Smith, courtesy the artist and Turner Contemporary, Margate

John Smith

still from Horizon (Five Pounds a Belgian) 2012

HD video, seamless loop (cycle 18min), colour, sound

© John Smith, courtesy the artist and Turner Contemporary, Margate

Like Brakhage, Welsby has also been fascinated by the endless dispersal of ocean light. In his film Drift 1994, a study of winter light falling on the continually moving surface of water, a misty pall cloaks the visibility of objects at sea. The dominant colour is grey – a grey iridescent with blues and greens.

Still from Rosa Barba’s film White Museum (2010) projected onto the seafront at Turner Contemporary, Margate

© Rosa Barba, courtesy the artist and Turner Contemporary, Margate

Since opening in Margate in 2011, Turner Contemporary has exhibited and commissioned a number of artists who have responded to its namesake’s legacy, including John Smith with his film work Horizon (Five Pounds a Belgian) 2012, and Rosa Barba with her 2013 exhibition Subject to Constant Change. For three months, Smith filmed from the large ‘picture window’ of the gallery and around Margate, capturing dramatically changing weather conditions. His intention is to collapse the poles of distance and involvement to create for the viewer a simultaneous sense of being outside and inside, as Turner’s late works achieve. To accompany her inter-related filmic sculptures installed throughout the gallery space, Barba presented a selection of Turner’s perspective studies that the artist had used to illustrate his lectures at the Royal Academy.