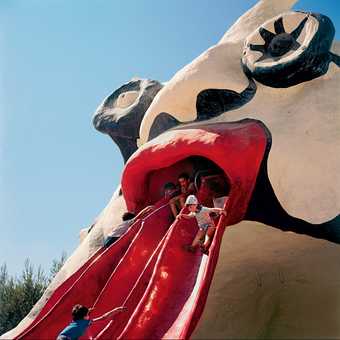

Niki de Saint Phalle’s Golum, Rabinovich Park, Jerusalem 1972

© Estate of Niki de Saint Phalle, courtesy Tom Little and The Playground Project

In the late 1940s Danish sculptor Egon Møller-Nielsen placed Tufsen, an abstract play sculpture, in a public park in Stockholm. It marked an important moment as art, play and public space started to interact with each other in a new way. It also broke new ground for the design of play equipment, which became more joyful and appealing for both users and designers. Furthermore, it revealed that playgrounds - as Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck was advocating at the same time in Amsterdam - could take on a significant role for the city, fostering a different relationship between children, families and their neighbourhood. In the following years play sculptures proliferated throughout Europe, the United States and Japan, as artists, urban planners and activists embraced the playground as a field for experimentation.

The installation of Tufsen was part of park commissioner Holger Blom’s initiative to improve the quality of life in the fast-growing city of Stockholm. An organic, abstract shape in a pool of sand, it was art that could be touched, climbed on and crawled through. American architectural critic and photographer GE Kidder Smith brought this novelty to the United States. He travelled to Sweden in 1939-40 as a fellow of the American-Scandinavian Foundation to research modern Swedish architecture. His findings were presented in Stockholm Builds, a travelling exhibition shown at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1941, and subsequently published in Sweden Builds in 1950, which also included images of Møller-Nielsen’s play sculptures. Swedish architecture, with its comprehensive planning, became a model for public buildings and housing.

Egon Møller-Nielsen's Spiral Slide c1956

Courtesy CBS Broadcasting Inc, New York

In 1953 Frank Caplan, the founder of the toy company Creative Playthings, also visited Sweden, met with Møller-Nielsen and started to market his play sculpture Spiral Slide. Thus, for the first time something other than steel pipe swings, monkey bars and see-saws was available to buy. Caplan frequently contacted MoMA for advice on design, and deliberately chose abstract play equipment for his catalogue. Philadelphia, America’s most progressive city in recreation planning and playground design, became an important client of Creative Playthings and helped to provide broad media coverage for new products.

Play Sculpture, a division of Creative Playthings established in 1953, co-sponsored a nationwide play sculpture competition, organised with Parents Magazine and MoMA. Playground Sculpture opened at MoMA in 1954, featuring 360 models including life-size examples of the winning entries, two of which were produced and sold through Play Sculpture. The show formed part of the institution’s influential promotion of modernist architecture, contemporary design and abstract art. Through exhibitions, educational programmes and model houses in the museum’s garden, good design was presented as a part of everyday life, and a meaningful childhood became linked to modern design, abstract educational toys and art education.

Joseph Brown working on model of play sculpture Whale Yard, c1954

Courtesy University of Tennessee, Knoxville

The need to build more recreation facilities for the baby boomers and the interest in creative playground designs boosted the demand for abstract play sculptures. The European model remained dominant - a fact criticised by, among others, American boxer and artist Joseph Brown. A resident fellow in sculpture at Princeton, he encouraged his students to go beyond developing variations on the Møller-Nielsen theme and started to come up with his own ideas.

A figurative sculptor, he forged a radically new aesthetic of play design, which brought him into contact with renowned architects such as Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius. In a letter to Brown, Breuer wrote: ‘These are I believe magnificently simple, sympathetic and dynamic instruments and succeed in being first-rate sculptured objects.’ His ‘dynamic instruments’ consisted of rope and/or steel and fully acquired their sculptural quality when children played on them, the rope’s instability and unpredictability demanding quick reactions and communication. Brown termed them “’Play Communities’ and they included the so-called Swing-Ring, which seems to have inspired many play structures up until today. But back in 1955 no manufacturer was interested in mass-producing them.

The enthusiasm for modern life paralleled the decline of the inner city, especially in the US. Publications such as The Death and Life of Great American Cities 1961 by Jane Jacobs highlighted the fact that the ‘white flight’ to the suburbs and the destruction of entire neighbourhoods in the name of urban renewal led to the slow decline of the city. Neighbourhood associations and city officials tried to stem the tide by clearing empty lots and creating small recreation areas known as ‘vest pocket parks’. In New York, the parks department invited artists to be part of festivals, events and happenings to revitalise Central Park and other public spaces by bringing people together, strengthening the local community and making the metropolis safer. The urban crisis of the 1960s showed that design was not enough. Real change needed human presence, or as American artist Robert Rauschenberg wrote in 1968 in his Proposals for Public Parks:

All cultural activities should, I believe, be dependent on participation and involvement by the inhabitants in their specific localised environment. It is essential to break down the sense of exclusivity, foreignness and imposed prestige of conventional attitudes about art.

Group Ludic's Submarine, Les Pins de Corduan: Royan, France 1969

Courtesy David Liaudet

The same was true for play sculptures and playgrounds in general. They underwent a transformation from places solely for children to collective and non-exclusive spaces, a shift taking place parallel to the development of Land Art, Allan Kaprow’s Happenings, or the idea of a museum without walls championed by visionary curators such as Pontus Hultén or Harald Szeemann. Play sculptures, whether temporary or built out of scrap materials, abounded as artists and urban activists explored new possibilities in collaboration, participation and art-making. In reaction to a materialistic society dominated by TV culture, artists provided accessible, playful and non-commercial tools for children and adults to liberate the senses and connect to the human and natural environment.

The members of Group Ludic, a French collective formed in 1968 in Paris by architect David Roditi, sculptor Xavier de la Salle and film-maker Simon Koszel, insisted that play sculpture should never be a ready-made solution. Prior to their collaboration, they had observed how children got involved with an outdoor sculpture exhibition - integrating the works into their play activities, or even throwing stones and trying to destroy them. This ‘cruel’ art handling would inform the group’s understanding of play sculpture: an object that could be transformed into a play machine by the child. As a consequence, its members would not design structures without the children’s participation. They tested a wide range of forms and materials to allow kids to connect with their environments, which often happened to be monotone leftovers in France’s newly built satellite cities. Group Ludic designed different types of modular objects by using industrial materials and built numerous playgrounds, none of which survived.

The Lozziwurm play sculpture, designed by Yvan Pestalozzi in 1972, at the Carnegie Museum of Art as part of The Playgroud Project 2013

Courtesy Josh Franzos

In 1969 de la Salle and Roditi contributed two play sculptures to the Play Orbit show at the ICA in London, described in the accompanying catalogue as an ‘exhibition of toys, games and playables by people who are not professionally involved with the design of playthings, but who work in the field of visual arts’. More than 100 artists participated, among them Barry Flanagan and Tom Phillips, as well as eleven art colleges with a broad range of projects.

The history of play sculpture and playgrounds in general can be understood as yet another overlooked chapter of modernism. Connecting play, art, education and public space, it finds itself at the centre of some of the twentieth century’s most pressing issues. Playgrounds became lively, interactive and imaginative public spaces. If they were too small to stop the urban blight, they nevertheless provided room for art outside institutions and away from bureaucracy.

Group Ludic's Spheres playground, Hérouville-Saint-Clair 1968

Courtesy Xavier de la Salle, Group Ludic

Today, the years between 1940 and the late 1970s appear to be the golden age of playground design. With the rise of safety standards, liability lawsuits and a general commercialisation of public space, playgrounds have become yet another expression of a society obsessed with standardisation, control and helicopter parenting.