Production shot of Kenneth Clark at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, for Civilisation 8 - The Light of Experience 1969

Courtesy BBC Archives

Italians call the great fourteenth-century authors Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio ‘i tre coronati’ - the three crowned laureates. In Britain, during the middle third of the twentieth century, art history had its own tre coronatiin the formidable shapes of Nikolaus Pevsner, Ernst Gombrich and Kenneth Clark (1903-83).

What made them stand out from their contemporaries both here and abroad was not just their extraordinary erudition and prolific output, but an eloquence and popularising skill that made them public figures. They became the subjects of biographies and many of their books remain in print. Pevsner, as the author of the landmark Buildings of Britain series, was in countless car glove compartments; Gombrich wrote the best-selling art book of all time, The Story of Art; and Clark was the maker of pioneering TV series which were broadcast internationally, the most famous being Civilisation 1969.

Opening credits of Kenneth Clark's Civilisation 4 - Man: The Measure of all Things 1969

Courtesy BBC Archives

Of the three, Clark’s reputation is most in need of rescue. Two people bear much responsibility for his eclipse: the art critic John Berger and Clark’s son Alan. Berger’s TV series and book Ways of Seeing 1972 laid down a Marxist-feminist gauntlet to Clark’s world view. Clark is the only art historian to be named, cited and ticked-off twice over. His description of Gainsborough’s portrait of Mr and Mrs Andrews on their country estate (Mr and Mrs Andrews c1750) in Landscape into Art 1949 as ‘enchanting’ and ‘Rousseauist’ is denounced:

They are not a couple in Nature as Rousseau imagined nature. They are landowners and their proprietary attitude towards what surrounds them is visible in their stance and their expressions.

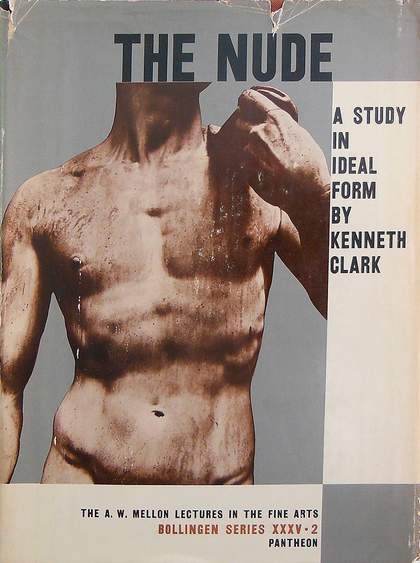

Clark’s The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form 1956 was also taken to task: ‘Kenneth Clark maintains that to be naked is simply to be without clothes, whereas the nude is a form of art.’ Berger concedes that the nude ‘is always conventionalised’, but insists it ‘also relates to lived sexuality’. The female nude is subservient to the male ‘spectator-owner… men act and women appear’.

Cover of Kenneth Clark's The Nude: A Study In Ideal Form, published by Pantheon Books 1964

If it has become hard not to consider Clark through Berger-tinted spectacles, it is even harder not to blot out the ‘lived sexuality’ of his son - the boozy Thatcher-adoring Alan Clark MP, whose sybaritic diaries outsold his father’s art books, and who was proud to be Lord Clark of Civilisation’s barbaric antithesis. When in 1997 he sold to the National Gallery his father’s serenely austere Zurbarán still-life A Cup of Water and a Rose c1630, I am ashamed to say that my admiration for Clark senior’s discernment (and envy of his deep pockets) was disturbed by a stray thought - did Clark junior get rid of it because its sobriety irked him?

In many ways, Clark became a victim of his astonishing success - inherited wealth (Paisley cotton); first book, The Gothic Revival, published at 22; youngest ever (at 30) director of the National Gallery; at 37, the greatest Leonardo scholar ever known; chairman of the Arts Council and Independent Television Authority. Books such as Landscape into Art and The Nude are now enthusiastically lambasted, but in their day they were ground-breaking surveys that mapped and synthesised vast fields for the first time. The Nude single-handedly revived interest in antique sculpture and its influence on Western art after a century of Ruskin-induced neglect. The vogue for Grand Tour studies, and Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny’s fine survey Taste and the Antique 1981, are inconceivable without it (in an otherwise positive review, Gombrich criticised Haskell and Penny for failing to mention The Nude). Now there are shelf-loads of books about nudity in art, all using The Nude as springboard and whipping boy, and nudity has been a key component of recent art.

Clark’s successors have lamented his cultural conservatism; his patronage of the neo-Romanticism of Nash, Piper, Sutherland and Moore; and his dislike of pure abstraction - Ben Nicholson’s reliefs, which he none the less collected, were less ‘cosmic symbols’ than ‘tasteful pieces of decoration’. But the condescension of posterity is disproportionate, and not just because ‘it is only an auctioneer who can equally and impartially admire all schools of art’ (Oscar Wilde). In retrospect, Clark was right about pure abstraction: it was a cul-de-sac, however magnificent at times. Mondrian’s road to abstraction is thrilling; once he gets there, I think his art becomes repetitious. Martin Hammer recently drew attention to Clark’s pessimistic essay published in The Listener in 1935 entitled ‘The Future of Painting’, in which he argued that a viable new style ‘can only arise out of a new interest in subject matter… We need a new myth in which the symbols are inherently pictorial’. Jackson Pollock is a case in point - he struggled to infuse abstract art with profound content and, by the time of his death, had returned to figuration. In post-1960s art and theory, impurism - conscious and unconscious subject matter - is all the rage.

Leonardo Da Vinci

A Grotesque Head 1502

Chalk on paper, 390 x 280mm

Above all, Clark was a brilliant weaver of words, the best since Ruskin and Walter Pater, whom he greatly admired. Today, when most art historians write like lawyers and accountants, his deeply pondered eloquence is needed more than ever. His influential interpretation of Leonardo’s grotesque heads from the 1930s is a tour de force. Having noted that Leonardo loved drawing freaks, he observed:

Mixed with his motive of curiosity lay others, more profound: the motives which led men to carve gargoyles on the gothic cathedrals. Gargoyles were the complement to saints; Leonardo’s caricatures were complementary to his untiring search for ideal beauty. And gargoyles were the expression of all the passions, the animal forces, the Caliban gruntings and groanings which are left in human nature when the divine has been poured away.

Leonardo’s man with ‘nut-cracker nose and chin’ is the counterpart to ‘the epicene youth’, and these types can be found scarcely modified at all stages of his career:

These are, in fact, the two hieroglyphs of Leonardo’s unconscious mind, the two images his hand created when his attention was wandering, and as such they have an importance for us which the frequent poverty of their execution should not disguise. Virile and effeminate, they symbolise the two sides of Leonardo’s nature… Even in his most conscious creations, even in the Last Supper, they remain, as it were, the armature round which his types are created.

It’s time for the Caliban critical gruntings to give way to a fairer assessment.