Jesse Maycock

King Alfred 1961, Museum of English Rural Life

Photo: Tate

When I was approached a couple of years ago to co-curate an exhibition of British folk art, I was initially a little hesitant. I am an American for one thing, and the word ‘folk’ comes with baggage, freighted with notions of the homespun or even kitsch. It is a word that some art historians and curators have a problem with. Before moving to the UK I spent a few years in the Deep South, and there discovered first-hand the rich practice of Outsider Art, which I would contend is as culturally significant to that region as the Blues or barbecue. That experience opened my eyes to looking for art in less likely places, and I have spent the past year searching collections across the British Isles, hunting for the best of what you could call folk art.

unknown artist

Horse Vertabrae Wesley

Painted bone, 122 x 135 x 135mm

British visual culture today draws from its own rich history of folk art, from signage and advertising right through to fine art. With artists such as Tracey Emin making quilts and embroideries, Grayson Perry producing tapestries and pots and Bob and Roberta Smith painting signs, what were once traditional approaches have been updated, embraced and even appropriated in contemporary art. It has been more than a decade since Jeremy Deller and Alan Kane’s Folk Archive first brought attention to a wide range of contemporary folk art pursuits at the turn of the millennium. Now seems the perfect time to explore great examples of historic folk art in the UK.

Queen Elizabeth II entering High Wycombe Town Hall through an archway made of locally made chairs, April 1962

There is also a desire in the air to look beyond the mainstream canon of art history. A proliferation of exhibitions such as The Encyclopaedic Palace at the 2013 Venice Biennale, the various presentations of theMuseum of Everything in Venice, London and elsewhere and the Hayward Gallery’s The Alternative Guide to the Universe, with their central focus on the work of Outsider Artists, have proven popular with audiences and critics alike. Personally I think these shows are important because they counter a tendency in much of contemporary art to favour increasingly younger artists who sometimes can be drawn to an obscure and theoretical practice. As the art critic Dave Hickey succinctly put it: ‘Today, anybody can make a work of art that nobody understands.’ One antidote is to entertain a more straightforward and direct kind of creativity.

British Folk Art is not an attempt to locate a history of Outsider Art in this country, though there are overlaps. Many artists can rightly be called self-taught, naïve, or a number of other terms that at some point become more or less interchangeable. Broadly speaking, Outsider Art involves a self-taught artist working in a particularly idiosyncratic, highly individual manner, often with motives driven by compulsion, desire or religious fervour. A generalisation about folk art, however, would be to say that it has its origin in tradition. It has been passed down and is therefore representative of a sense of the collective. What becomes fascinating, then, is finding the most intriguing and original examples of these art forms.

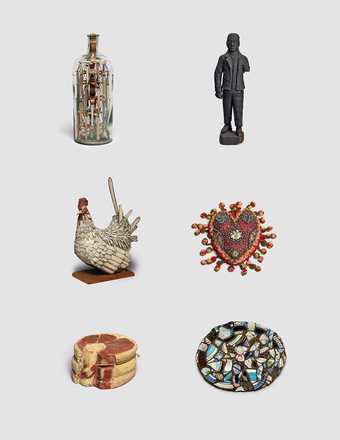

Clockwise from top right: Chimney sweep sign, painted wood, 1020 x 380 x 250mm; Heart pincushion, fabric, beads and pins; Tin tray covered with boody including part of a broken doll, c.1900, tin and broken ceramic, 420 x 240mm; Joint of beef shop display, painted wood, 195 x 190 x 115mm; Model of a cockerel made of bone, c.1797-1814, carved bone 230 x 120 x 230mm; Bottle with bobbins, glass and bobbins, 300 x 100mm

Particularly interesting has been discovering forms new to me, such as the spirit vessel, or ‘God in a bottle’, which features small wooden sculptural votive offerings suspended in a bottle of clear liquid. Also found in the north-east of England are examples of boody ware, the nineteenth-century practice of fixing ornate broken crockery and china to tin platters, the results of which are reminiscent of Gaudí or Julian Schnabel’s plate paintings. At Norman Cross in Cambridgeshire, French POWs from the Napoleonic War used bone, wood and metal to create intricate and extraordinary sculptures.

The exhibition spans some 300 years from the mid-seventeenth to the mid-twentieth century; an end date that reflects the period before folk art arguably became a commodity or too self-conscious. It includes the work of professional sign painters and wood carvers, as well as ‘non-artists’. Needlework samplers made by an educated class of teenage girls sit alongside wool work embroideries fabricated by sailors and elaborate quilts created by convalescing soldiers in the aftermath of the Crimean War.

George Smart

Goose Woman c.1840

Image courtesy Tunbridge Wells Museum and Art Gallery

Highlighted figures include the tapestry artist Mary Linwood, who made textile reproductions after famous paintings, the enterprising George Smart, the tailor of Frant, and, probably best known of all, the St Ives painter Alfred Wallis. But this is ultimately an exhibition of strange and exquisite objects, created mostly by unknown makers. At a time when 3D printing can manufacture guns or replicate machines with moving parts, the reminder of the handmade object, with its brilliant imperfections and anomalies, is something to celebrate.