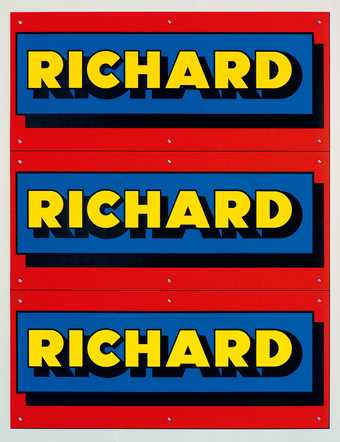

Richard Hamilton

Advertisement 1975

© Estate of Richard Hamilton, courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of Vicki and Kent Logan

In an essay titled Romanticism, written in 1972, Hamilton defined a theme - it might almost be a formula - which remained central and constant in his art and ideas, as well as pliable to shades of political or moral expression:

I have, on occasions, tried to put into words that peculiar mixture of reverence and cynicism that ‘Pop’ culture induces in me and that I try to paint. I suppose that a balancing of these reactions is what I used to call non-Aristotelian, or, alternatively, cool.

In this merger and balancing of ‘reverence and cynicism’, he identified a particularly modern position, and one that might be seen to enable the artist to engage with the technological and cultural dynamics of a Mass Pop Age. Hamilton had been one of the first anatomists of the burgeoning mass culture imported from America to Europe during the 1950s, writing his celebrated ‘Pop Art Is…’ letter to the architects Peter and Alison Smithson in January 1957. Oft quoted, his definition of Pop Art comprises a list of eleven qualities which hold true for the mass culture of the computer age, nearly 60 years later (they describe precisely, for example, a contemporary phenomenon such as Grand Theft Auto):

Popular (designed for a mass audience), Transient (short-term solution), Expendable (easily forgotten), Low cost, Mass produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big Business.

But as important as the acuity of this list is, the fact remains that, as Hamilton later noted:

At the time the letter was written there was no such thing as ‘Pop Art’ as we now know it. The use of the term here refers solely to art manufactured for a mass audience. ‘Pop’ is popular art in the sense of being widely accepted and used, as distinct from Popular Art of the handcrafted, folksy variety.

In short, he was analysing a socio-cultural shift that was taking place beyond the self-reference of fine artistic terminology, yet of crucial importance to the ways in which visual art might be conceived, made and experienced. Later still in his career, Hamilton would speak more personally about his intentionality as an artist, explaining that he could never understand the thinking of a ‘non-allusive’ art that sought only to address itself and its own concerns; while for himself, he wanted to make art that was ‘multi-allusive’, engaging with the secular totality of the modern world, rather than a sanctified and exclusive notion of artistic purity. Tellingly, he would add: ‘But I was after beauty, too.’