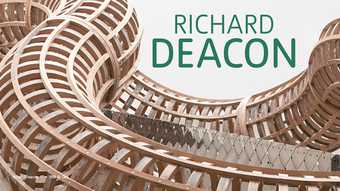

Richard Deacon

Two by Two 2010

Galvanised and stainless steel, 242 x 258 x 230 cm

© Richard Deacon, image courtesy FIAC, Paris

Simon Grant

You have a collection of objects that you have arranged on your shelves in the studio over the years. Why did you collect them, and have they inspired your work?

Richard Deacon

I have collected things all my life and been, in various ways, obsessed with those I have bought, found or otherwise acquired, though funnily enough quite recently I have noticed that other people have begun to find this assembly of stuff interesting. I think this in part reflects changes in the sensibilities of the art world – the recognition that there is no such thing as neutrality in display, for example, or the increased awareness of, or attraction to, obsessive behaviour. While clearly I am an artist known for producing objects, the fact that my studio contents seem to tell a more complicated story is intriguing. There is a great deal of autobiography hidden within my shelves – a piece of iron slag picked up in our back garden in Dorset when I was about five (I thought it was a meteorite); toy bullock carts from Sri Lanka bought there when I was about seven; my mother’s toy zoo animals and her stethoscope; my A-level physics books; some of my children’s toys, including a few I made for them. These are somewhat sticky and a great many other things have gathered around them. There are a large number of toy animals – mostly plastic. I did have a collection as a child, but didn’t keep it. However, when my children were young, I found myself disturbed by the poverty of verisimilitude in, for example, Playmobil animal figurines. I am someone who is very interested in differences of kind – I’ve always been a bird watcher – and I thought that Playmobil’s representations reduced the particular to the general and impoverished experience.

The animals are organised in two broad divisions – farm or domestic and wild. The latter are further subdivided into land and marine animals. This collection forms a central shelf. Above and on the left (as you look at it) are more organic residues – bones, skulls, shells, nests, insects, etc. Above and to the right are mineral things – rocks, fossils, crystals. Below the central shelf is a more random collection of heavier rocks and pieces of wood, but also bits of plastic and metal that have structures or forms that I have found interesting – Marge Simpson’s hair, for example, or distorted rolls of old masking tape. Above and on the right of the central shelf are mostly cultural or anthropological items – stone tools and hand axes, wooden shoes, containers in various materials, weights, writing instruments, head rests, dolls, toys, figurines, jewellery. Standing in front of the shelves is a wooden ladder made by the Lobi people of Burkina Faso. Hanging off that are a number of coils of rope and string, all handmade but in a multitude of different fibres and materials. On the very top shelf are a number of larger dolls, figures and other toys, as well as a stack of the school books I mentioned and some baskets and boxes from various parts of the world.

Collected objects on shelves in Richard Deacon's studio, October 2013

Courtesy the artist

Simon Grant

You are interested in sculptures carved directly out of the rock surface – such as the Ellora and Ajanta caves in India, as well as various rock-carved churches in France. When you were a child living in Sri Lanka you saw the carved Buddhas at Polonnaruwa, which had a great effect on you…

Richard Deacon

They terrified me. These three twelfth-century Buddhas, one sitting, one standing and one lying down, were huge, and of course as a six year-old, I was half the height I am now, so they appeared twice as big. I could see that the rock was the same and therefore they had somehow been formed from the cliff face, but I couldn’t imagine what possible agency was involved. The cliff wasn’t there, but the Buddhas were: something huge was missing and something huge was present. What felt like a vibration in the air between these two irrefutable facts with no way of reconciling them was what I found terrifying. It left a deep impression, connected to a raw physical apprehension of presence and absence.

The caves at Ellora and Ajanta were a different thing. I’d looked at a couple of French rock-carved churches, particularly the church of St Jean at Aubeterre-sur-Dronne, and I have a great interest in caves, especially those that have residues of human habitation (I’m not a potholer). I think the connection between house and cave is provocative – caves are, after all, not built.

The Ellora caves, Aurangabad, India, 2000

© Bruno Poppe, courtesy Richard Deacon

The group of caves at Ajanta is Buddhist rather than Hindu, dating from around the first century BC to about the seventh century. The monks extended and enlarged the existing spaces by carving to bring both stupas and rows of benches into the caves, as well as frescoing the walls. At Ellora, developed between the sixth and ninth century, Buddhist, Hindu and Jain caves overlap each other, and here the urge to enlarge developed in such a way as to progressively liberate the cave from its surrounding rock. The astonishing Kailasanatha temple to Vishnu from the ninth century, covered inside and out with intricate detail and standing on rows of elephants, is carved out of a single block from the surrounding cliff face (which still exists as an entrance screen behind which the temple stands). I visited here in 2005 and thought that this was the most incredible way to produce architecture – to start with a solid and carve the building out of it.

Some of Eduardo Chillida’s sculpture seems, in spirit, to be a bit like this. I’ve long been interested in carving, but somehow I’d always thought of it as related to the lump and couldn’t get much further. It was the experience at Ellora that prompted the, perhaps obvious, realisation that carving was also hollowing out, and therefore a route to construction. After all, what you have left when almost all the material has been removed is a kind of structural framework. I began to use hollowing out as a preliminary stage in constructing in ceramic and in stainless steel. The Range group of ceramic works from 2005 are one example, as are the series of stainless steel pieces Siamese Metal 2008–12 and the large stainless steel Congregate 2011.

I spent some time in the 1970s touring the gothic cathedrals of England. With their vast empty interiors and buttressed external walls, they have something in common with Asiatic temples in that they appear to be built around a space, rather than, as classical temples are, buildings housing something. The sculptures I have wanted to make have often adopted means that free the interior – they are, somewhat analogously, built around space. This seems to be the connection that the caves at Ajanta and Ellora opened up.

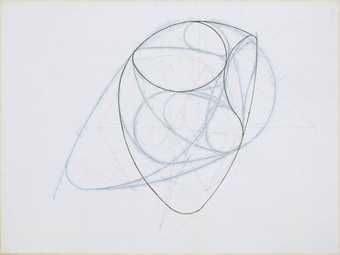

Richard Deacon

Restless 2005

Tate © Richard Deacon

Simon Grant

Claude Shannon’s book The Mathematical Theory of Communication 1949 has influenced your way of thinking. How have his ideas fed into your work?

Richard Deacon

I do like numbers. I remember learning to count, and the realisation that numbers were generated by rule, rather than being learned by rote, was revelatory: the certain knowledge that, given any number, the rule enabled me to generate the next was a powerful sensation. It was such a pleasure that I would spend long parts of entire days counting out loud, like some kind of speaking clock, in wonderment at the sheer inexhaustibility of numbers.

I took mathematics and physics as A-level subjects and understand how equations formalise relationships, and I am comfortable with there being a connection between those formalisations and the world. As a student I became interested in information theory and came across The Mathematical Theory of Communication with an introduction by Warren Weaver. Shannon was a signals specialist at the Bell Telephone Laboratories, preoccupied with the technical problems associated with the transmission of messages along channels affected by noise or interference. His theory is extraordinarily elegant and powerful, linking ideas about information, entropy and uncertainty with those of channel capacity. Weaver was a social scientist at the Rockefeller Foundation, and his introduction presciently transfers the problems that initially concerned Shannon to the levels of semantics and effectiveness, while emphasising that ‘message’ can be construed as being a function of any communications media.

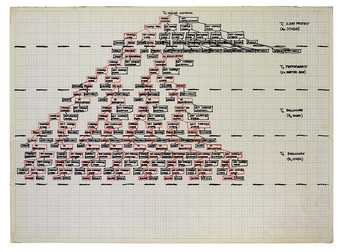

Richard Deacon

drawing for Stuff Box Object Project 1970

© Richard Deacon, courtesy the artist; courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

As I worked through the text, I began to realise that ‘noise’ in a communications channel, whatever the intention of the originator, is something very like the artwork itself, introducing a high level of uncertainty and thus an extraordinary amount of information into the perception or reception of the work. Information is, of course, different from meaning (gibberish has a high information content), but it is the possibility that meaning(s) arrive in the clutter of uncertainties that makes things interesting. The artist is thus a kind of noise maker.

Richard Deacon

Art For Other People #12 (1984)

Tate

Richard Deacon

It’s Orpheus When There’s Singing #7 (1978–9)

Tate

Simon Grant

Artists often have affinities with other artists, especially from the past. Whose work have you enjoyed looking at and thinking about over the years?

Richard Deacon

In 1973 I travelled across America trying to see the works of David Smith and Jackson Pollock, including sleeping outside the locked gates of Smith’s studio at Bolton Landing; at the Royal College I visited many times Caius Cibber’s Melancholy and Raving Madness 1670s, which were then on show at the Victoria and Albert Museum; in 1985 I criss-crossed Montagne Sainte-Victoire on foot thinking about Cézanne and visiting his studio; in 1989 I travelled through southern Germany looking at altarpieces by Tilman Riemenschneider; in 1991 I trekked into the Venezuelan Andes to see the church and furnishings built by the naïve artist Juan Felix Sanchez (1900–1997). However, Donald Judd has probably been the artist I’ve been most continuously interested in and challenged by, and the one who has liberated me the most.

Donald Judd

Untitled (1980)

Tate

© Donald Judd Foundation/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2025

The first work of Judd’s that I saw was in Tate’s The Art of the Real show in 1969. I was a foundation student at Somerset College of Art and we’d gone up to London on a coach trip from Taunton to see the exhibition. The Judd was a vertical stack – a series of galvanised steel boxes with pale purple plexiglas tops and bottoms running from floor to ceiling in one of the gallery spaces. I had no real idea what I was looking at. It puzzled and troubled me, somewhat in the same way the Buddhas at Polonnaruwa had done.

I’m not uninterested in ordering. Just before going to art school I worked during vacations at an agricultural feed mill and was very absorbed by the various ways in which differently sized bags and sacks were stacked to achieve a secure load on a pallet. I was also a stamp collector and spent hours arranging coloured squares and rectangles to form sets on the page. And stacking dishes to dry while doing the family washing-up of an evening was always a pleasure, so perhaps the memory has something to do with a recognition of a correspondence with those kinds of ordering (like with like) and with the confusion of finding it in a gallery.

The second time I encountered Judd’s work was at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London in 1970, and, shortly after that, in two shows at the Lisson Gallery, also in London. The Whitechapel exhibition was mostly of metal boxes on the floor, plus a couple of progressions on the wall. The first Lisson show was entirely of wall-mounted boxes, while the second included three very large wooden boxes (probably 5ft cubes) occupying a wall downstairs. I was by this time a student at Saint Martin’s School of Art and very interested in American art. These were clearly important shows and I recall that I really wanted to get something from them, yet it was with some embarrassment that again I realised I didn’t really know what it was I saw. They were difficult, ungiving things to be looking at, and I had no vocabulary for doing so. It was uncomfortable. The group of wooden boxes was the first work that I felt okay with. This was largely because the material characteristics of the grain on the shuttering ply had some attraction, and the problem of dealing with the thin edge of an angled piece meeting a flat face evoked something familiar for me. But I was also aware that this was a frail straw to be clinging to.

Donald Judd

Untitled (1972)

Tate

© Donald Judd Foundation/VAGA, New York and DACS, London 2025

At the same time I sort of knew what I was supposed to be looking at, or what I was supposed to be seeing. The group of students I hung out with at Saint Martins were avid readers of Artforum, storming into the library each month for the latest issue. And, when it came out, we all had copies of Gregory Battcock’s book Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology. This collection was sufficiently well known to produce appropriate obscene graffiti in the toilets of art schools. So it wasn’t that I didn’t know, it was more that I couldn’t see.

In the second half of the 1970s Judd’s art became very relevant to me as I thought about his practice. For instance, I began to make works that were always ‘whole’: starting with a shape and a material – a quantity of material configured in a given shape, such as a square or disc – and restricting my actions to within those parameters. This was also a recognition that the real is significant (as in The Art of the Real), and that Judd’s work was concerned with what was real. However, I didn’t believe this was all that mattered. Cans of paint or counting are interesting only if there is also a discourse where they can be seen to be interesting. Partly to do with my developing a way of making akin to folding something up, and partly to do with the issues of meaning and of discourse, some questions about the inside and the outside things, and about what lay between them, became, and remain, important to me. I also thought that, despite the apparent austerity of Judd’s practice, its consequences were never prescriptive but, rather, liberating, certainly on the very fundamental question of material and what it was possible to work with. The core of this liberation seemed to be that material was allowed to retain, at a simple level, its connectedness to the world, and was thus ‘real’. Meaning, however, was a more difficult issue, whether in terms of the experienced object or of the experiencing subject. I thought that Judd’s empiricism, while empowering, at the same time disenfranchised the subject.

In 1984 I met him for the first time, at an exhibition titled Sculpture In The 20th Century at Merian Park in Basel, Switzerland. I was a surprising inclusion, and was awed to find myself in the company of artists whose work meant a lot to me. Judd showed a very large, multicoloured enamelled aluminium piece. On being introduced, I said what a pleasure it was to meet him and something about the work, to which he replied: ‘It’s brand new.’ This was puzzling, but something that I heard him say on other occasions. It either meant it was a new kind of thing, or, intriguingly Warholian in its connotations, that it was one of a new range, a new kind of product.

In 2002 I had an experience that I can only describe as an epiphany. This was Thomas Kellein’s exhibition Donald Judd, Early Work 1955–1968 at the Kunsthalle Bielefeld in Germany. Installed in the Philip Johnson building, it was breathtaking.

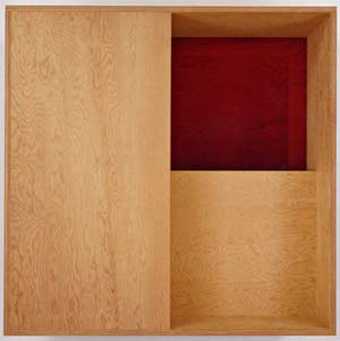

Donald Judd

Untitled 1987

Plywood with red Plexiglas

© Donald Judd Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

The show comprised 30 paintings, twenty drawings, eight objects and eight larger works. The ostensible motifs of these early paintings are unprepossessing, banal interiors and nondescript street scenes -entrances, bridges, paths, bleak gardens, stairwells. They have something in common with Rothko’s early subway paintings, representations of fairly compressed spaces in a muted palette. The motifs are repeated in successive paintings, the detail progressively reduced until there is a kind of equality across the picture, the framing character of a motif and the space between being equally valued, equally solid or equally empty. A concrete bridge spanning a park segues into a band of dark colour and then into the bent tube connecting two painted panels. A relief painting from 1961, a black painting with an inserted baking tray, belonging to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, has a folded object, which encloses a space, framed within a textured black surround. This surround is read as a wall, situated in space, fenestrated by the partially reflective folds of the baking tray, which it compresses, holds and dematerialises. Yet at the same time the textured black is empty, a space or an absence, lacking surface. The object within this is there, present, plain to see.

The value that Judd extracts from these humble paintings and drawings and from the subsequent reliefs is quite extraordinary. There is no revelatory vision, no laying bare of transience, but a progressive, insistent assertion that object and space are coincidental, equal and important; that this is how the world is. The world is not pushed away or schematised, but is solidly in front of us, factual. I had completely misunderstood, thinking that geometry was a kind of idealisation – systematisation or purity – as it is in Constructivist art, from which Judd’s work was generated. The reverse is true: geometry is a fact, not a schema.

Richard Deacon

Little Assembly 2010

Dried porcelain powder forms in acrylic display case, 600 x 597 x 155 mm

Simon Grant

You recently bought a 3D printer. The possibilities of 3D printing for manufacturing and medicine are huge, but what about for artists? What impact has this technology had on the way you think about materials?

Richard Deacon

I first tried to do something with this technology in 2001 through the Centre for Visual Research in Dundee. That didn’t work out, but the idea that the virtual could transfer into the real – that information could become production – remained enticing. The next foray was in Germany when Dick Lion, a porcelain specialist who works with the master ceramicist Niels Dietrich from time to time, came across a university department that had developed a prototype machine using dry porcelain powder, printed with water jets to build a form (an application for high-temperature electronics components). This was in 2008 and drawings for some works we were making with Niels and Dick had already been transferred to computer to make rather difficult shrinkage calculations. These were thus scaleable and printable within the dimensional constraints of the prototype machine. The resulting edition was of ten matchbox-sized pieces, collectively titled Little Assembly 2010. I have continued to follow the technology as it has developed through the numerous articles that have appeared – and by talking to people. Last year, when I began looking for a larger-scale colour printer, the IT company I work with told me that small 3D printers using ABS plastic had come on to the market at a more or less affordable price. It seemed like a logical next step and the printer was installed in the studio a few months ago. I had thought to use it to model a commission I am working on for Groningen in Holland, but this turned out to be a bit like wanting to run before I could walk. It’s unclear what will eventually come out – the most intriguing thing so far has been the discovery of an app that enables me to use my mobile phone as a scanner and then, via the cloud and a bit of tweaking, get a printable file. Amazing.