During the final fifteen years of his life, until his death in 1954, through simple arrangements of coloured paper, Henri Matisse developed a radical and in some senses unprecedented style, which also acted as a new and inimitable medium that he had invented. Through the so-called paper cutouts, and their application to a range of projects, he was able to infuse contour with sculptural form, give paper the transparency and luminosity of stained glass, or evoke the convulsive surface of water. This manifested itself through a prolific series of designs for stained glass windows, ceramic tile murals, book illustrations, church vestments and other textiles.

Numerous photographs of Matisse’s studio from this time document the cut-outs as contingent objects, existing in a state of perpetual flux and transformation. The way in which they were pinned to the walls and then adjusted, recut and recombined to create an environment that transcended the boundaries of conventional painting, drawing and sculpture is striking to contemporary eyes. Part of their appeal for Matisse, it seemed, in addition to the greater ease the process afforded him in reaching the final, resolved state of a given work, was their ability to be continually reconfigured and rearranged and have multiple possible states – all of which were captured in photographs.

‘In the history of art,’ wrote the philosopher and social critic Theodor Adorno, ‘late works are the catastrophes.’ The transcendent cut-outs of Matisse would seem to be described by Adorno’s essay Late Style in Beethoven, which discusses the composer’s final compositional phase and speaks of ‘the hand of the master [which] sets free the masses of material that he used to form; its tears and fissures’ in order to create ‘fractured landscapes… [torn] apart in time’. Matisse’s cutouts, begun as an expedient to help him to make compositions for paintings and designs for book and magazine covers, became the summation of a life spent working with both contour and colour, not to mention one of the most extraordinary and indeed greatest late periods in any artist’s career. So much so that in his 2006 study, On Late Style, Edward Said ranked them as one of the supreme examples of an artist’s late work in any medium: ‘Each of us can readily supply evidence of how it is that late work crowns a lifetime of aesthetic endeavour. Rembrandt and Matisse, Bach and Wagner.’

Henri Matisse

design for cover of Verve IV 1945

Gouache on paper, cut and pasted, mounted on canvas 365 x 555 mm

© Succession Henri Matisse/DACS 2014, courtesy the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

If Matisse was largely confined to his house and studio during his final years, this in no way impeded the reception of his cut-outs, which were widely seen and much written about almost from the moment they were created. Their earliest unveiling began as their making did – with illustrated books and periodicals for journals such as Cahiers d’Art in 1936 and Verve in 1937. The early projects for& Verve, of course, fed directly into Matisse’s thinking behind Jazz, his first masterpiece in the cut-out medium which was published in 1947. Initially, however, this radical development in his art was met with scepticism. As Christian Zervos, the co-founder and director of Cahiers d’Art, and the person who had therefore commissioned Matisse to make his first cut-out work, wrote retrospectively and in rather grudging terms in an article in 1949: ‘I’m willing to admit that Matisse, having entered the game of the paper cut-outs as if by chance with the coloured cover done for Cahiers d’Art in 1936, later converted it into an agreeable distraction which would ease his long hours of insomnia!’

The implication of this decidedly faint praise was clear: such a ‘game’ was perhaps a permissible indulgence for an artist in their dotage, but no real substitute for the main task of painting. While the proliferation of the cut-outs in the early years of their publication and reception as maquettes for journals seems to have had a double effect: it introduced them to the public as a striking and novel development in Matisse’s work, but it also reconfirmed them, even if inadvertently, as design or decoration, rather than as independent works of art per se.

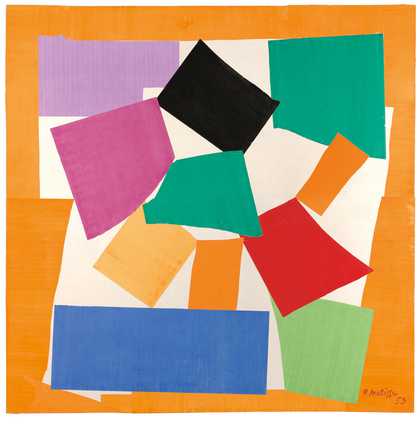

Henri Matisse

The Snail 1953

© Succession H. Matisse / DACS 2014

Although the artist acknowledged that he had gained ‘greater completeness and abstraction’ in the cut-outs and ‘a form filtered to its essentials’, he always maintained an ambivalent and sometimes sceptical attitude to abstraction, made manifest through the cut-outs themselves and the words he used to characterise them to his interlocutors. ‘A purified sign for a shell’ was how he described in similarly careful terms – balanced between abstraction and figuration – his first cutout on the theme of a snail’s shell. His second work on this subject –Tate’s The Snail of 1953 – was one of the most abstract Matisse ever made. Rather than cutting into the coloured sheets of paper that had been painted with gouache, he now tore and ripped into them directly, as if the size and sheer excitement of producing this large-scale piece demanded it. The concentric composition is formed by coloured sheets, which radiate out from the centre in contrasting colours of red and green, orange and blue, and yellow and mauve, echoing the spiral pattern of a snail’s shell.

A colour photograph taken by Matisse’s assistant Lydia Delectorskaya is particularly interesting for our consideration of the way in which works were created together in the studio at this time. It shows that The Snail was originally (or at least momentarily) one panel in a larger composition, forming the left-hand side of a triptych made up of Memory of Oceania 1953 on the right and Large Decoration with Masks 1953 in the middle, so they were made in tandem with each other and presumably used some of the same coloured sheets and elements.

Henri Matisse

Memory of Oceania 1952-3

Gouache on paper, cut and pasted, and charcoal on paper mounted on canvas 2844 x 2864 mm

© Succession Henri Matisse/DACS 2014, courtesy MoMA SCALA, Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York

Begun during the summer 1952 and completed early in 1953, Memory of Oceania, as the title makes clear, was Matisse’s way of evoking places from his past to which he knew he could no longer return, as well as aspects of the world that lay outside his studio windows and were now beyond his reach: swimming in the sea, walking in a garden and, in this particular case, his visit to Tahiti in 1930, where he spent three months when aged 60. The increasing escalation of scale and ambition, as he was emboldened by each piece that came before, combined with an ever-quickening pace of production in the final two years of his life is remarkable. Each of these works was completed in an ever-closer race with death – against death, in fact. As Matisse knew all too well, labouring ceaselessly to make these apparently effortless compositions, creation is hard work, with no time to spare.