Elisabeth Bronfen on John Everett Millais’ Ophelia 1851–2

Sir John Everett Millais, Bt

Ophelia (1851–2)

Tate

Ophelia has become an icon for femininity in despair. Reduced to the part of a pawn in a network of intrigues, abandoned by her brother, abused by her lover and manipulated by her father, her only way out is an excessive, histrionic display of vulnerability. Lying forever on her back in a stream, flowers floating beside her, she is perfected. No longer resisting the power play around her, she will fulfil the destiny others have scripted for her. In Millais’s painting the palms of her hands open upwards suggesting that she is abandoning herself to some higher force. But seen together with her partially opened lips, these hands evoke something else as well. Perhaps she is in the process of receiving something; perhaps she is caught in a moment of solitary enjoyment. Above all, she is making a statement. She is on display for an implicit spectator. Her immaculately posed body says ‘look at me’, less in reproach than in pride. She knows her performance is aesthetically pleasing. She knows that in our memory she will survive as a beautiful dead body.

In Shakespeare’s text, her demise is not directly shown, nor are we offered an eyewitness report. Instead, Queen Gertrude presents what is already an interpretation – a tableau of death. Locked into her solitary anguish, Ophelia is forever framed by someone else’s story. Death, according to the queen, is to have been an accident, even though in perfect correspondence with the young woman’s troubled state of mind. In her report, Ophelia’s point of entry into the stream is a willow, an emblem of mourning because deserted lovers proverbially hang garlands on its boughs. Dead men’s fingers is the name chaste maidens call the flowers Ophelia has chosen for her wreath. Both the scene and the accessories help to turn the displayed feminine body into an allegorical figure of forsaken love. In the queen’s words Ophelia did not actively choose death, but rather wistfully surrendered herself to the laws of gravity. The breaking of a twig caused her to fall, and as her garments became heavy with the stream’s water, she was pulled to her muddy grave. Yet for a moment the wide-spread clothes sustained her while she chanted melodies, as if unaware of her precarious situation.

The focus of Millais’s version isn’t this curious interlude between life and death. His Ophelia is completely immobile. She isn’t singing, nor is she slowly drowning. Instead, she is caught in a realm that obeys neither the laws of gravity nor those of mimetic representation. The water around her is perfectly calm. The flowers that have glided from her hand and are now covering her belly and her sex seem hyper-real, superimposed on the murky rendition of the submerged body parts. The right hand seems detached; its texture different from the chin and neck, it floats on its own. The richly embroidered blouse, making the breasts imperceptible, is pure materiality, catching light, sparkling – another body fragment. Both Ophelia’s life and her death have been arrested. She lies forever suspended along the liquid boundary. She has been transformed into an allegory for the duplicity of art’s pathos. Because it sustains death, it is immortal.

John Paul Lynch on Thomas Cooper Gotch’s Alleluia 1896

Thomas Cooper Gotch

Detail of Alleluia 1896

Oil on canvas

1333 x 1841 mm

© Tate

I have seen this painting in at least two different rooms at Tate Britain and it has always caught my eye.

I like the way the frame is an active part of the experience and overall enjoyment of the picture, as opposed to being purely for decoration. It is made up of Ionic-like columns on both sides, with an entablature across the top that joins them together. The frame is all gold, as is part of the background.

Although I was brought up as a Roman Catholic, I am not particularly religious. But I enjoy places of worship, and I actually get the feeling of being drawn into this painting. (The small arch that is visible in the picture even gives the appearance of a halo surrounding the head of the most central figure.)

The painting, to me, seems ahead of its time and reminds me in some way of the work of Gilbert & George. Just as they superimpose images over different backgrounds, Gotch makes it look like the girls that he has portrayed are suspended over a gold background.

Thomas Cooper Gotch’s Alleluia was presented in 1896 and is part of BP British Art Displays at Tate Britain

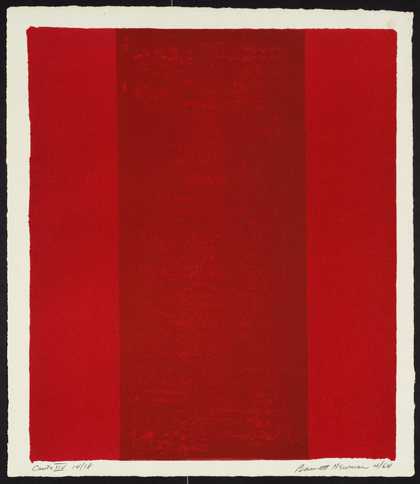

Callum Innes on Barnett Newman’s Eve 1950

Barnett Newman

Eve (1950)

Tate

In 1980, as a student at Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen, I attended a lecture on the work of Barnett Newman. It was given by an American historian and, God, was it boring. He simply rattled through it showing image after image on low-quality 35 mm slides. He didn’t talk about the human quality of the painting at all.

Later that year I went to see Eve at Tate for the first time. The gallery had bought it a few months previously. Nothing prepared me for the physicality of the picture.

It is hard to talk about details in Eve. The detail is really in the layering of the paint; it is the whole painting. As you stand before it you are confronted by the physicality of the cadmium orange paint and the emotions that this colour can evoke. His work has no narrative, no design. It is meant to be felt. Then the fragility of the edge of the purple band (the ‘zip’) running up the right-hand side comes into play. The zip gives the painting both its complexity and its simplicity, its human fragility, its total ‘rightness’ and its radical beauty.

Newman used to talk about how there has to be a potential for failure in a painting for it to work. If there is a possibility to fail, then that makes it more interesting – which is an idea I like to put across in my own work.

Barnett Newman’s Eve was purchased in 1980

Lucinda Hawksley on John Everett Millais’ Ophelia 1851–2

Sir John Everett Millais

Detail of Ophelia 1851–2

Oil on canvas

762 x 1118 mm

© Tate

Although this painterly water barely ripples at the surface, we are seeing the stream in its calmest moment. The patterning of the weed suggests it can mutate into a fast-flowing, exhilarating river, in which young lads could splash and compete in the style of E.M. Forster’s or D.H. Lawrence’s prose. A river in which one could become a mermaid.

If I stare long enough at Millais’s rendering of the water, it can return me to a trance-like state of my own water-based memories. Of being a small child swimming in an outdoor pool. I loved that pool. It was shaded by thick trees, and in the late afternoon, when the sun had moved behind them, their shadows afforded the illusion of a green river. In my imagination it became wild unbounded water instead of a safe rectangular pool (hemmed in by tiles and concrete) – a Swallows and Amazons world of rushing rivers, through which brave explorers journeyed to find exotic wildlife and treasure. It also transports me back in time to adult months spent in New Zealand, where lakes and rivers are still unpolluted and safe. It evokes that unparalleled sensation of sun-warmed skin, made grimy with hours of dusty walking and travelling, being cooled by the purest of water.

Ophelia’s death throes can be read as a moment of ecstasy. An ecstasy experienced by a woman usually trammelled by the conventions of her society, or of her imagination, who has come to regard her existence as mere drudgery, and who has finally found freedom.

John Everett Millais’s Ophelia was presented by Sir Henry Tate in 1894