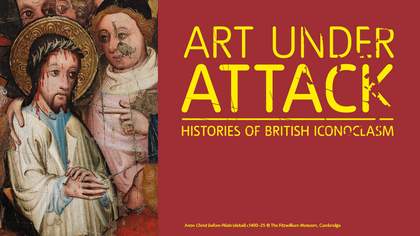

Douglas Gordon

Self Portrait of You + Me (David Bowie) 2007

Burnt photograph, mirror 632 x 530 mm

© Douglas Gordon, courtesy Gagosian Gallery

In 1957 the artist Gustav Metzger mounted an exhibition of damaged art in King’s Lynn. Treasures from East Anglian Churches was a selection of sacred artefacts that had been attacked during the period of iconoclasm between the English Reformation in the 1530s and the Commonwealth of 1649-1660 when Britain, under the Puritan Oliver Cromwell, was effectively a republic. Metzger already knew plenty about annihilation. Born to Jewish parents in Nuremburg, he was evacuated via Kindertransport to England in 1939 at the age of twelve, just as Nazi Germany was engaging in genocide against its own people. His parents disappeared soon after. In the 1950s he was involved in activism, first with the Committee for Nuclear Disarmament and then as a founder of the Committee of 100. Later he made art born of material violence - nylon panels that he corroded with acid, and liquid crystal projections that melted and reformed under the heat of the projectors. He called it Auto-Destructive Art.

Metzger, argues Tate curator Andrew Wilson in the catalogue for the exhibition Art Under Attack at Tate Britain, was not an iconoclast in the classic sense. Rather, he understood something that iconoclasts have often failed to grasp. Breaking an image does not eradicate it; it merely replaces it with another. Destruction is part and parcel of creation. Treasures from East Anglian Churches demonstrated just this fact: cruelly mutilated artworks had transformed into powerful warnings against the latent violence of political and religious dogma.

Dead Christ 1500–20

Photo: courtesy of the Mercers' Company © Louis Sinclair

There were periods of iconoclasm in Britain before the Reformation, of course. In the late fourteenth century the Lollards, an heretical sect founded by John Wycliffe, waged war on idolatry, removing statuary and images - ‘dead stones and rotten sticks’ - from churches and destroying them. The Lollards protested that these objects were venerated as if they were alive, while the poor citizenry was left to subsist in wretchedness. As with many iconoclasts, their actions revealed a paradoxical anxiety over the liveliness of artefacts; some Lollards claimed that religious imagery and statuary were hiding places for demons which lured worshippers into idolatry.

The (progressive) mistrust of (old-fashioned) superstition burned bright among Protestant iconoclasts during the Reformation a century and a half later. They were troubled by complex ontological questions. How does a representation embody its subject? Is it possible for one material – bread, say – actually to transubstantiate into another - flesh, for instance - in certain sacred circumstances? The Catholic clergy claimed not only was it possible, but that the church alone was capable of effecting such a change. The Protestants were unconvinced. Today, these issues remain unresolved. It is difficult, painful even, to treat a photograph of a loved one (as an oft-cited example) merely as chemical emulsion on paper. When the subject of an image is not only loved but divine, the problem of its ontological status could hardly be more explosive and far-reaching.

British School Portrait of Oliver Cromwell Inverness Art Gallery

The central visual focus of every medieval Christian church was a sculpture of Jesus on the cross, usually fixed on a rood screen at the emtrance to the chancel. Many roods were strikingly lifelike; the one from Boxley Abbey in Kent could move its eyes, lips and arms. Protestant reformists seized it in 1538 and paraded it through market towns, showing off the rods and wires that manipulated it as proof of the fraudulence of the Catholic church. In a sermon at the pulpit of Paul’s Cross in London, Bishop Hilsey gave it to the congregation to smash to pieces. Not a single medieval rood survives in a British church today.

The Mercers’ Hall in London is built on the site of the destroyed Catholic Church of St Thomas of Acon. The only remnant of the church is a medieval marble statue of the dead Christ, which was discovered buried under the hall in the 1950s. The prone figure lies with mouth open and wounds still seeping; its abundant pathos is compounded, however, by missing feet, an arm and a hand - all smashed off by sixteenth-century iconoclasts. As Bruno Latour asks in the catalogue for his 2002 exhibition Iconoclash: Beyond The Image Wars in Science, Religion and Art at ZKM, Karlsruhe: ‘What does it mean to crucify a crucified icon?’ Does it constitute a double negative, a denial of the message of Christ’s death? Once again, the iconoclasts have left us with an image more poignant and enduring than the one they sought to erase.

‘A second point that must be made about the life of artefacts is that it is their normal fate to disappear,’ writes the art historian Dario Gamboni in The Destruction of Art 1997. It is often those objects that are most resistant to disappearance - either through their material solidity or through the care with which they are preserved - that incite iconoclasm. The last remaining hunks of Thomas Becket’s shrine, from Canterbury Cathedral, attest to the weight and density of the rose marble from which it was carved. While the two fragments appear gnawed, like hard chocolate, they are far from pulverised. J.M.W. Turner’s watercolour Tintern Abbey: The Crossing and Chancel, Looking towards the East Window 1794 shows not only the dilapidation of the Cistercian abbey, abandoned in 1536 during the dissolution of the monasteries, but also the stoic endurance of its graceful arches seen two and a half centuries later.

Even when an artefact does disappear, taken out of circulation either by an aggressor or someone determined to save it, its absence may amount to a fresh image that is equal to or greater than its original. Think of an empty plinth or a vacant picture frame. Beside the former site of Becket’s shrine, the cathedral’s flagstones are polished smooth by three centuries of kneeling pilgrims. If the history of Reformation iconoclasm can be seen as a kind of exorcism (even if the exorcists claimed not to believe in the ghosts they were trying to expel), then it was ultimately a failure; it caused more hauntings than it purged.

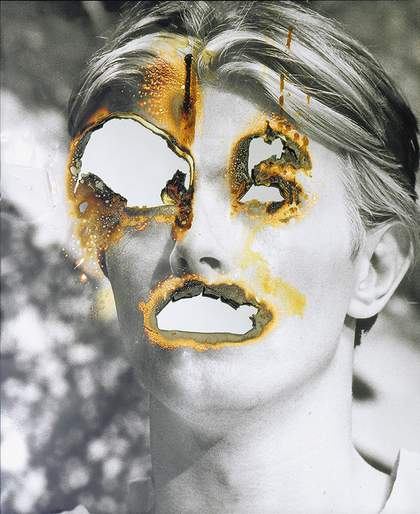

John Stezaker

Mask XIII (2006)

Tate

Not all iconoclasts are naïve to the generative potential of destruction. When iconoclasm is a form of political or religious protest wrought by a minority against the face of the status quo (rather than a state-sanctioned process of societal reform), the creation of powerful new images may well be the intended outcome. In 1866 high-spirited vandals made nocturnal additions to John Nost II’s equestrian statue of King George I, located in Leicester Square. A contemporary newspaper photograph shows the king’s horse adorned with black spots, and both the monarch and his mount wearing conical dunce’s caps. It is a wonderful image; apparently it was born of no particular complaint except a general derision towards the former king. (The British antipathy towards false idols - religious, political or cultural - remains one of the nation’s defining characteristics.)

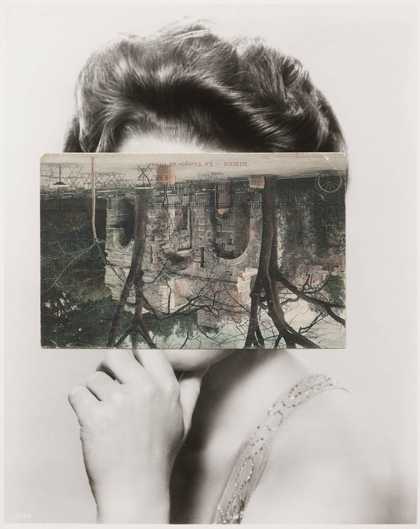

Other protests were more focused. The years 1913-1914 saw a crescendo in the militant activities of the suffragette movement, spearheaded by attacks on paintings hanging in public museums. Mary Richardson famously sliced the canvas of Diego Velázquez’s The Toilet of Venus (The Rokeby Venus) 1647-51, while Mary Wood took a cleaver to John Singer Sargent’s portrait of the writer Henry James. Some targets were paintings of women, others depicted men. The iconoclasm of figurative images is often cited as evidence of society’s repressed but deeply rooted belief in the animism of objects - as if to slash a portrait with a knife was to harm the subject itself. But the suffragettes’ anger was not directed at the diverse subjects of these images, rather at the cultural authority that the artworks represented.

John Singer Sargent, Henry James 1913 (damaged)

National Portrait Gallery

It is likely that the suffragettes were in the minds of two women when they splashed paint stripper on to Allen Jones’s sculpture Chair 1969 on International Women’s Day in 1986. They were never caught, but the action was assumed to be a feminist protest about the work’s degrading depiction of a woman. In contrast to the suffragettes’ protests, however, their assault seemed very much aimed at the artwork. That is not to say, of course, that harm (actual or metaphorical) was intended to the woman the sculpture represented, nor, in all likelihood, to the artist himself. Rather, the perpetrators aimed their iconoclastic gesture at the web of ideas - to do with status, value and representations of gender and sexuality - that the sculpture is enmeshed within.

The same is broadly true of Peter Stowell-Phillips’s attack on Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII 1966 at Tate in 1976. Stowell-Phillips claimed that by splashing blue dye on to the work’s pale white firebricks he was protesting against the use of taxpayers’ money for the purchase of such art. Ironically, Andre’s notorious sculpture traces its aesthetic and ideological heritage directly back to the Protestant Reformation and the iconoclastic Puritan movement that arose in the following years. The artist hails from New England, where the Puritans settled after leaving Europe in the early seventeenth century, and he freely admits the influence of its culture on his Minimalist, anti-representational, anti-superstitious, rational art. Stowell-Phillips, like the vandals who took hammers to the Mercers’ dead Christ, has unwittingly delivered to us another double negative: a denial of a denial.

Carl Andre

Equivalent VIII (1966)

Tate

In the decades following the late 1960s and 1970s Puritan revival in the guise of Minimalism, images have flooded back into contemporary art. The kind of ascetic vision proposed by the likes of Andre is hard to maintain for long in the information age. Today, artists seem to fret not about whether to allow images into their work at all, but which ones, and to what end. Perhaps this is the delayed influence of Marcel Duchamp, who often saw creativity as a process of choosing from the world of already existing objects. Duchamp penned a moustache and goatee on to a postcard of the Mona Lisa (L.H.O.O.Q. 1919); almost 100 years later, Jake and Dinos Chapman have added their own cartoonish ‘improvements’ to artworks by artists such as Francisco Goya and William Hogarth, Douglas Gordon has burned holes into photographic portraits by Andy Warhol (and others) in his series Self Portrait of You + Me 2007, and Kate Davis traced outlines of her body over vintage catalogue illustrations of Amedeo Modigliani’s drawings of women.

Jake and Dinos Chapman One Day You Will No Longer Be Loved II (No.6) 2008

© Jake and Dinos Chapman

‘What has happened that has made images… the focus of so much passion?’ asks Latour. ‘To the point that being an iconoclast seems the highest virtue, the highest piety, in intellectual circles?’ The answer, surely, lies somewhere between the mired conflicts of British religious history and the instantaneity of today’s globalised digital media. Images are important, says Latour, not merely as ideological ‘tokens’, nor as ‘prototypes’ for whatever it is they represent. Images, through their inevitable destruction, allow us ‘to move to another image, exactly as frail and modest as the former one - ut different’.