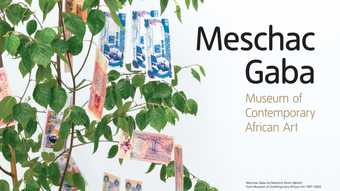

Meschac Gaba

detail of Music Room; Library

Museum of Contemporary African Art, 1997-2002

Installed at Kunsthalle Fridericianum, 2009

Meschac Gaba is an artist who, from his early days in Cotonou, Benin, has managed to construct a universe of his own. From one work to the next, it is as if he were reciting different paragraphs of an artistic manifesto. And the general framework is clearly stated: while considering himself a citizen of the world, Gaba refuses to fall into the globalisation trap. At a time when some would love to have us believe we have entered the era of post-ethnicity, a jarring intellectual absurdity, his work wears its rootedness proudly, and at times even betrays a certain pan-Africanist posture.

Despite being the creator of a piece called Palace of Eternity 2001, he is conscious of the finitude of our world and the necessity of leaving our descendants tangible traces – tools that can help them to decipher what we were. If history is supposed to be written by the winners, he took it as his mission to write a history of his own that would counterbalance the dominance of Western notions of heritage and contradict the cultural fate Africa was stigmatised with.

Meschac Gaba

detail of Music Room; Library

Museum of Contemporary African Art, 1997-2002

Installed at Kunsthalle Fridericianum, 2009

The Museum of African Contemporary Art installation is, in my opinion, the spine of Gaba’s work. He may have given it a date of closure – 2002 – but it represents for me a lifetime commitment. As the artist himself says:

I would not wish the Museum of Contemporary African Art to be considered for itself, simply because this museum is part of my body of work and forms part of several pieces I have created.

In other words, the entirety of his past and future production is naturally finding its place in the virtual space that is called upon to contain everything. But limiting the museum to a simple aesthetic proposition would be a tragic misunderstanding. His concept goes far beyond simple artistic questions, encompassing as it does history, politics, ethics and philosophy.

There are all sorts of museums in Africa, but none, at least to my knowledge, that is dedicated to contemporary art. Not even in Dakar, where the Pan African Biennale of contemporary art has been hosted for more than two decades. In creating his museum, Gaba is making a statement directed to African states and Western countries. The message is simple: in the future, we will have at our disposal a museum in which we will define ourselves, our own practices, our own aesthetics and our own historicity. Still, the pirouette is to be relished: an artist who is the founder and director of his own proper museum – a museum that, unlike all the great Western temples of contemporary culture, is mobile and can be set up for the duration of an exhibition in any corner of the planet.

Meschac Gaba

detail of Salon

Museum of Contemporary African Art, 1997-2002

Installed at Kunsthalle Fridericianum, 2009

Meschac Gaba, without perhaps even realising it entirely, is applying a corrective to the history of past centuries. By once again placing Africa at the heart of universal creation, he is not content simply to affirm a forgotten and negated presence, but stresses his own existence as somebody who wants to get rid of the posture of the eternal victim. What is more, he confirms his will to turn the page of a no longer applicable history by staking a claim on the contemporary field, that is to say, the here and now – a position that is resolutely meant to face the future.