Even as commuters swarm on the pavements, even in its rush-hour pomp, even at the mid-morning peak of its fibre-optic frenzy, for all its lit glass towers and civic monuments, every industrial city is haunted by its opposite.

Sometimes, we glimpse this alter-city in sci-fi films and comic books, in acts of God. As I write this, I’m in a twentieth-floor hotel room in downtown Boston. I was due to fly home days ago, but the winter storm they christened ‘Nemo’ has put paid to that. Below me, the city is in lock-down. All restaurants and shops are closed. Cars are banned from roads, with the threat of a year in prison for violators. All flights are cancelled. No trains are running. There are power cuts, although mercifully this hotel is still switched on. As I look out of my window, the hive-life of the city has gone, and I see it as a landscape for the first time. Snow drifts prop up shop-fronts and billboards, traffic lights are dead eyes. It looks more like a mountain range than a metropolis. This is, to quote W.H. Auden, ‘altogether elsewhere’. If I blink, I half expect to see those herds of reindeer from the end of his poem The Fall of Rome sweeping down the main street ‘silently and very fast’.

LS Lowry

The Empty House 1934

Oil on plywood, 43.2 x 51.3 cm

Still from Andrei Tarkovsky's Stalker 1979

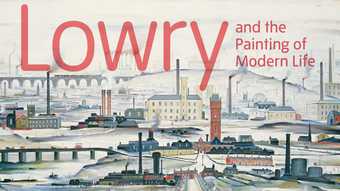

But this sense of an alter-city, with all its post-apocalyptic resonances from movies, didn’t start for me with sci-fi or comics. It was there in my childhood, in the prints on the walls of my family home in Manchester, in the works of L.S. Lowry. Manchester has a claim to be the first true modern city, cradle of the industrial revolution, birthplace of the computer, proving ground for Engels, et al. And its greatest painter was captivated by that modernity, that expansion, that energy. His evocations of the city going about its working life were a part of the fabric of my childhood in the 1970s. My mum – who was brought up a few streets away from Lowry – used to point at figures in the paintings (I recall in particular the war veteran on the trolley in The Cripples from 1949) and tell me stories about them, how she saw them on the street corner, local gossip…

But Lowry’s vision of Manchester didn’t stop at the everyday city around him. He saw the alter-city too, and painted it. It’s there as early as 1934 in The Empty House, in which the once grand façade of an abandoned home is set in a landscape out of Tarkovsky’s sci-fi classic Stalker, with a pool of stagnant water, stubbled grass, splintered trees like broken fingers. The following year, in River Scene (Industrial Landscape), Lowry gives us a wider view of the alter-city. These are the industrial edgelands, overlooked and overcast. Under grey northern skies a wide shot opens up, of mill chimneys, machinery, a line of fence posts with gaps like a bad set of teeth. And then there’s a house, half submerged in… what? The slopes of the scrubland leading down to the river, I think, but it could almost be the river itself, or the sky. The elements here refuse to remain in their rightful places.

L.S. Lowry

Industrial Landscape (1955)

Tate

By the time Lowry painted The Lake in 1937, the skull beneath the skin of the Lancashire landscape was clearer than ever in his paintings. It’s tempting to make easy links from his life in the late 1930s (nursing his sick and dependent mother) to the bleakness of these canvases, but this strand in his work is more than just a response to his circumstances. Brought together, these alter-city images amount to a compelling and singular vision. For a painter sometimes dismissed as too concerned with the gritty reality of northern working life, these are visionary paintings. This is north-west England as post-apocalyptic film-set. Here, in The Lake, he gives us again a glimpse of another world. This is no Sunday boating lake, but a rough-edged sprawl of water, a huge slick or spillage. It looks thicker than Manchester rain, this lake that half-swallows boats and buildings and trees. It looks more like sump oil or radioactive residue. It looks like it needs warning signs all round it. Except no one goes there. At least, hardly anyone, just a clutch of figures on a slope in the middle distance. As the poet Roy Fisher said of his native Birmingham in 1961 when he wrote his ground-breaking sequence City: ‘Most of this has never been seen.’ That’s the thing about the edgelands, the wastelands, our industrial alter-cities. Most of them don’t get much looking at. And here is Lowry in the 1930s showing us what we’re missing.

L.S. Lowry

Blitzed Site 1942

© The Lowry Collection, Salford

When the war brought bombs to his city, Lowry the painter was ready for it. Paintings such as Blitzed Site from 1942 seem not so much a break in history but a continuation of the vision of those images from the 1930s. And that vision continues in his paintings of the 1940s and 1950s, in works such as Industrial Landscape and Industrial Panorama from 1953, but it reaches its natural (with hindsight, perhaps inevitable) completion in his later shockingly beautiful seascapes, in which the grey water and the grey sky have become almost indistinguishable, have overwhelmed everything else and demanded the whole canvas to themselves.

Some of our finest contemporary artists and photographers (most vividly, for me, the Coventry-born George Shaw) have discovered a visionary beauty in the post-industrial scrublands, housing estates, warehouses and factories of England’s north and midlands. We tend to think of this subject matter as edgily contemporary, which of course it is. But Lowry saw it too, more than 80 years before.