‘In general I hate Paris and all contemporary art, although alas I am half French!’ 24-year-old Marc Chagall wrote from his Montmartre studio in early 1912. ‘I think it’s impossible for us to mix up with the west… I don’t know the future but without doubt truth and purity are on our eastern side.’

Chagall missed his fiancée Bella, his family and home cooking. (‘It is impossible to eat here as well as in Russia’ he informed his sisters from the gastronomic capital of the world.) But then there was the Louvre.

Here before the canvases of Manet, Millet and others, I understood why I could not ally myself with Russia and Russian art. Why my very speech is foreign to them. Why they do not trust me. Why [the] artists’ circle ignored me. Why in Russia I am only the fifth wheel. I cannot talk about it anymore. I love Russia.

During the next decade, 1912–22, Chagall created his greatest works: the depictions of Jewish-Russian small town life then on the verge of obsolescence, made hallucinatory and monumental through the prism of memory and the artist’s idiosyncratic assimilation of Cubism, Expressionism and abstraction within his essentially narrative project. Jew in Red 1915, Green Violinist 1923–4, The Promenade 1917–18: each of these images of rabbis, musicians and lovers transforms humdrum life in his native Vitebsk shtetl into an intense psychic reality. And each emerges from his battle between Russian and French identity.

Marc Chagall

Le violoniste vert 1919

Gouache and pencil on paper

24.7 x 13.3 cm

The last Chagall retrospective in the UK took place at the Royal Academy in 1985, when the artist was still alive, and it contained not one loan from Russian collections. Since then, the opening of dialogue between the West and leading museums in Moscow and St Petersburg has transformed our understanding of what the Russian avant-garde brought to European modernism. Chagall’s paintings that have visited from there have revealed the innovative scope of this Russian period, and thrilled Western audiences.

Yet here is a paradox: as the Russian avant-garde consolidates its place in the story of twentieth-century art, Chagall is increasingly marginalised. No modern painter is at once so popular with the public and so disparaged by art historians. (He rates two mentions, en passant, compared with comprehensive analysis and scores of references to his contemporaries Malevich, El Lissitzky, Rodchenko and Kandinsky, for example, in Thames & Hudson’s standard Art Since 1900.) The challenge, a century after he mourned that he was ‘only the fifth wheel’, remains to place his early work in Russian context.

Chagall’s two teachers were Russian Jews who represented the national culture of their times: realist Yehuda Pen (1854–1937) and Léon Bakst (1866–1924), a member of the World of Art group and the Ballets Russes stage designer. He had fiercely competitive relationships with each of them, but took from the first the assumption that provincial life in the Pale of Settlement (the area of Russia to which Jews were restricted) was a subject for art, and from the second a knowledge of European trends, a flair for colour and a lifelong engagement with theatre.

Marc Chagall

Birth 1910

Oil on canvas

65 x 89 cm

Birth 1910, his last major work before leaving Russia for Paris in 1911, shows the impact of both. Like a curtain unveiled on a stage, the crimson hangings of a bed reveal a midwife holding a baby and the mother, pale and bleeding, lying on the mattress. She is the central, solemn figure; in comic counterpoint is her husband, crawling out clumsily from his hiding place under the bed, while in a corner, illuminated by golden lamplight, a huddle of whispering Jews await news of the birth. The bed and the outline of the mother recall Rembrandt’s Danaë of 1636, which Chagall knew from the Hermitage, but the parting of the curtains recalls Byzantine icons of the nativity, while the figure of the midwife, erect and in a frontal pose, resembles a primitive icon of the sort which also inspired Natalia Goncharova and even Malevich. In its fusion of Eastern and Western influence, Birth is a typical early Russian avant-garde painting; to its historic sources the artist added his own mix of Jewish mysticism and crude physicality – his illiterate mother suggested he bandage the stomach of the woman with a white cloth – evocative of quotidian Vitebsk.

Months after finishing the painting, Chagall followed Bakst to Paris against the latter’s advice (‘You’re nervy, but I’m even nervier. I don’t want to have to cope with you’). He attended life drawing classes alongside Fernand Léger – nudes were not part of the Russian tradition, thus the balance between savagery and emotional distance in the stark gouaches Nude with a Raised Arm 1911, Nude with Comb c.1911 and Nude in Movement 1912. ‘I love French blood. While gnawing at French painting, trying to overcome it, I wanted to savour the taste of a French body,’ he wrote in his memoir, recalling a liaison with his femme de ménage.

The nudes were private paintings; what Chagall showed in Paris, and sent home to Russia, was a series of works recasting his Vitebsk scenes in the newly learned language of Cubism. In the first, the Art Institute of Chicago’s Birth 1911, the shtetl interior of the 1910 painting is torn apart and reconstructed as shards of luminous blue darting above red floorboards composed of slatted triangles which tip whirling figures towards us; the baby is about to shoot out of an indifferent midwife’s arms, an acrobat walks on his hands. Geometric foundations now underpinned fantastical interiors full of disorientating perspectives and incongruous images, as in the cow and woman with an upside down head at a vertiginously slanting table in The Yellow Room, also from 1911.

Marc Chagall

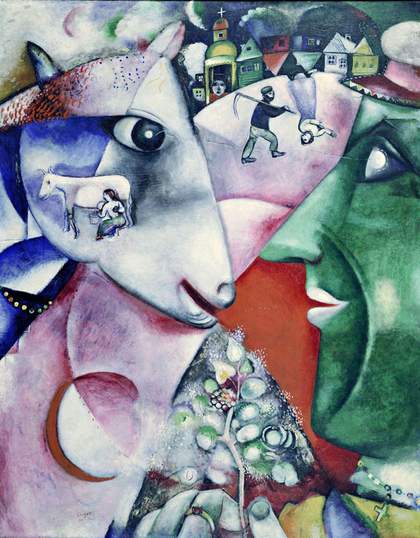

I and the Village 1911

Chagall ® / © ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2013

In I and the Village 1911, fragments of Russian memories – Vitesbk’s domed church and coloured houses, a peasant and a grim reaper wielding a scythe – rotate round a sun-like disk, with a cow’s head forming an arc opposite a green masked face. This was Chagall’s distillation of Russian natural and human life, frozen icon-like in the picture’s glassy surface, but made modern by the revolving forms of Cubism. Emotionally expressive but formally rigorous, it marked how the encounter with Cubism had radicalised Chagall even though he would not relinquish his individual motifs.

Waiting in Vitebsk, Bella saw his latest paintings, sent home – and rejected – for exhibition in Russia, and was shocked: ‘You mustn’t scare people, knock them off their feet with fear and rebuke. This is honestly – forgive me, crude, quote boyish. You can’t bark something at people – it isn’t artistic.’ When he returned to Russia in 1914 to marry her, these overheated colours, exaggerated forms and dislocated perspectives disappeared.

Pen and ink drawings – Departure for War 1914 – depict the everyday life of soldiers at the dawn of the First World War. Vitebsk also saw an influx of refugee Jews accused of spying, forced to leave their homes in western Russia. ‘I longed to put them down on my canvases, to get them out of harm’s way,’ Chagall wrote. The beggar above the snow-covered velvety town in Over Vitebsk 1922 is the eternal wandering Jew; heavy but weightless, his disproportionate presence – he is taller than the church dominating the picture – suffuses the commonplace landscape with mysticism.

Marc Chagall and family photographed by André Kertész in 1933

Works created in homage to Bella in 1915–16 – The Poet Reclining, painted on their honeymoon, The Strawberries, or Bella and Ida at the Table, after their daughter’s birth – are especially lyrical. How, to Malevich and the Suprematists who would determine the house style of the Bolshevik revolution, could Chagall appear anything other than bourgeois? Yet the key works of his career depend compositionally on Russian abstraction. Drawings such as Constructivist Portrait 1918 and Collage 1921 are experiments in the genre; more frequently, he now answered abstraction by assimilating it within its opposite – the pictorial human drama of love and fear that was his unique contribution to modernism. Jew in Red is a symbolic, transcendent figure, suggestive of wisdom and an instinct for survival, because it is also modern, ironic, distorted by sharp contrasts of rounded forms, zigzags, edgy lines, geometric shapes. Thrilling to revolutionary liberation, in The Promenade Bella spins on Chagall’s arm like a banner, waving over cubic houses and a sky composed of geometric elements; the ornamentation of the pleats of her skirt, as in a Cubo-Futurist rendering of movement, enhance the dynamic effect.

‘All Russia is acting,’ noted writer Viktor Shklovsky during the civil war of 1920. ‘Some kind of elemental process is taking place where the living fabric of life is being transformed into the theatrical.’ We see that happen in the seven Jewish Theatre Murals 1920, from Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery, which Chagall knew were both his masterpiece and his swansong to Russia: he fled the country in 1922. With verve, fury and defiance, a Jewish dancer, a marriage broker, a scholar, an actor and an ethereal pair of lovers twirl across a stage and backcloth built of translucent Suprematist forms and still life depictions of fruit, fish, fowl and cake. The rhythms of art and life converge, the miraculous shimmers behind the ordinary order of things, the spiritual is given form through the command of abstract images, in a work which still announces Chagall as the most enduring figurative artist of the Russian avant-garde, and the most emotionally engaging one.