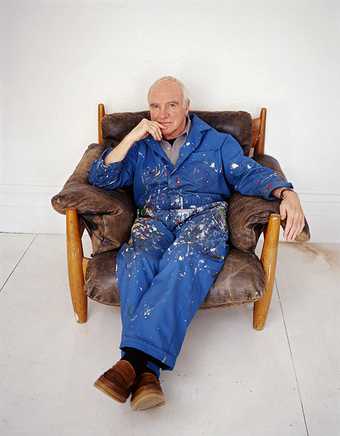

Patrick Caulfield photographed in his Belsize Park studio by Jillian Edelstein, 1999

My favourite photograph of Patrick Caulfield was taken by Jillian Edelstein in 1999. The artist is sitting low in a battered brown leather chair, wearing blue worker’s overalls which are splashed with paints of many colours. His hand is resting below his lip, and he’s looking straight at the camera, as if he has nothing to fear from its scrutiny. On his face is an expression, both amused and impenetrable, which anyone who met him will recognise at once to be characteristic. But, above all, you can’t help noticing how handsome Patrick is.

Of course the looks of an artist ought not to be a factor in judging their art. But just as it’s hard wholly to disentangle the work of van Gogh, Lee Miller or Modigliani from their extraordinary appearances – Giacometti looks like a Giacometti, Rembrandt like a Rembrandt – so Patrick’s own physical serenity seems to provide at least a parallel to his work. I’ve known very few people with such a profound sense of self-certainty. Artists in most disciplines are by habit neurotic, fretting either about their inadequacies or the unfairness of how they’re being received. Unforgotten slights and missed opportunities loom large, especially in conversation. But Patrick belongs among those very few who not only know what they want to do, but who appear not to care what anyone thinks of it. On one occasion, I was one of the first few people to be shown a painting – of a leg of lamb – over which he’d just spent the previous nine months. He took me into his studio and took away the dishcloth with which he’d covered it. As it happened, I loved it, and he was delighted. But he left me feeling that he wouldn’t have minded if I hadn’t. It was no good asking him where you might get to see so many of his earlier pictures. He’d given them to his dealer and thereafter lost interest. ‘Where are they, Patrick?’ ‘No idea. Don’t know.’

I first got to know him through my wife Nicole. I’d already noticed that most artists I met deferred to him. The very fact that he did not attract fellow-painterly jealousy tells you something about him. If someone asked Howard Hodgkin or Paula Rego which of their colleagues they most admired, they would usually say ‘Patrick’, as if his was the one name everyone could agree on. If you asked artists why he wasn’t better known – as famous, say, as Freud or Bacon – they’d reply: ‘Because he’s too good.’

The lazy way of looking at his work is to say that it’s painting about painting. The way he deploys colour and the way he mixes together objects and landscapes in wildly differing styles is usually taken to be some sort of comment on the arbitrariness of representation. And it’s true that in many of his pictures he does seem to be seeking to lay bare the definitive differences between one dimension and three. But in my own view he’s doing this not just as play, but to a purpose: he wants to show us the haunting unknowability of the environment in which human beings have to spend their lives.

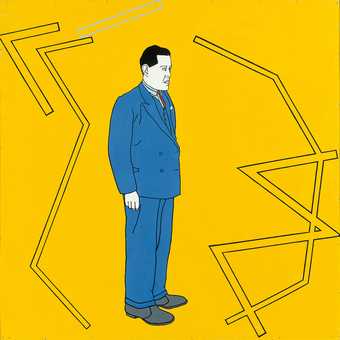

Was there ever a major painter who painted so few people? Even when he’d send me an occasional painting done for my birthday, or for a first night, then only my arm would appear, perhaps behind a curtain. Or just a curtain. Or a spotlight. Certainly no sign of me. Even Juan Gris, you will notice, painted to the nines, is left suspended by Patrick in starkly hostile surroundings. And was there ever anyone who ever portrayed so much food, while themselves being so completely uninterested in eating?

Patrick Caulfield

Portrait of Juan Gris 1963

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester (Wilson Gift through The Art Fund, 2006) © The estate of Patrick Caulfield. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2013

I’m not quite sure why we got on so well, though I suspect that the fact that neither of us knew anything about each other’s artistic past played a large part in it. We both valued wit as one of the highest human virtues. I certainly did not share his taste for whisky, or for companionable silence. By the time of day when we usually met up, he’d already have done his regular stint of morning painting, plus his steady hours on a stool in the Belsize Tavern, and he’d be ready to talk about anything. In the last days, when cancer of the jaw meant that he couldn’t speak, he would pass beautifully written little notes across. One, unforgettably, read: ‘Forgive me. It’s six o’clock in the evening, and this time always makes me sad.’ We shared a common passion for uncontemporary cinema, and I loved introducing him to Renoir films he didn’t know, because I was so sure he’d understand them. On the other hand, he remained unable to convince me in return that Ulzana’s Raid 1972, a western with Burt Lancaster, was the greatest film ever made.

By the time the drink really kicked in, at dinner, say, or after, then you would see flashes of a stuttering anger which could bring an evening to a halt – usually caused by his own inability to express in language thoughts and feelings he sets out so eloquently in paint. I was always aware that he was ruthless – ruthless as only an artist can be. It did not surprise me when the late impetus of his work was to strip away. He revelled more and more in unoccupied rooms, abandoned objects and lone exit signs. Latency became his subject. The world was charged, but unwilling to reveal itself. He’d always preferred to paint the record player rather than the band. One of his greatest pictures, after all, is of a stereo deck. But as the years went by, the formidable technical skills and the mastery of preparation became even more perfect, while the subject matter became ever more ambiguous. By the end, he could shock you with a pair of doors.

Ultimately, that’s his gift – to charge the canvas with feeling by methods which remain determinedly oblique. Our friendship was the same. He is buried in Highgate Cemetery directly opposite Ralph Richardson. It seems appropriate. Two people beneath whose impeccable, everyday surface lay unbearable sadness.