When I first saw Lowry’s industrial images I liked them very much, partly because there are places in the coal-mining region of Silesia in the south of Poland that look like this. But I was also interested in the other Lowry – the empty pictures, such as St Augustine’s Church, Pendlebury, painted in 1924, and Northleach Church 1947. They immediately reminded me of Caspar David Friedrich paintings, such as Winter Landscape with Church 1811 or The Abbey in the Oak Forest 1809–10. Friedrich is associated with the sublime, and I think Lowry’s paintings are sublime too. Very sublime and dark.

Caspar David Friedrich

The Abbey in the Oak Forest 1809-1810

Oil on canvas, 110.4 x 171 cm

St Augustine’s Church, Pendlebury and Northleach Church could represent the post-apocalyptic aftermath of Lowry’s more famous crowded images, which in turn could be a set from Andrzej Wajda’s 1970s film The Promised Land about a nineteenth-century industrial city in Poland and the desperation of workers in its cotton mills. I knew the sort of landscape portrayed by Lowry from my childhood, but the factory I knew is a positive thing. Positive in that it doesn’t kill, but provides the opportunity to work and is the hub of the neighbourhood. There is a train station, there is a park, there is a stadium and a sports field, a culture house, and everything is there thanks to this factory. I believe now when people look at what were thought to be such terrible conditions in Lowry’s paintings, they will think about what happened when the factories closed down and appreciate a part of the life being depicted.

Still from Andrzej Wajda's The Promised Land 1975

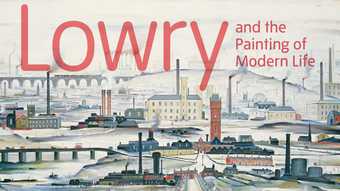

All of Lowry’s works are the same in terms of mood. If you put all his paintings together side by side, they could almost form a panorama, with their ever-present grey light engendered by fumes from the factory. They’re definitely nostalgic. His paintings may or may not be documentary, but they are certainly symbolic. When the streets are shown in perspective, that perspective is closed by the factory. So what is the destiny of these people? It’s the factory.