Marc Chagall

Homage à Apollinaire 1911–12

Oil on canvas

200.4 x 189.5 cm

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2013, collection Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

Even for an eclectic artist such as Marc Chagall, his painting Hommage à Apollinaire 1911–12 is something of an anomaly in terms of its intensity and complexity. A man and a woman whose bodies are joined at the hip are caught in an impossible vortex that spits out fragmented geometric shapes in rose gold, olive, crimson, blue, pink, amber and maroon; several poets’ names; part of a clock face; and the author’s name. The last is inscribed twice – once in its entirety and once as a linguistic amalgamation of Latin and Hebrew. The overall impression is of something that was once whole splitting into parts.

As indicated by the title, this expansive composition was motivated by the artist’s admiration for the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. In the bottom left-hand corner, Apollinaire’s name appears alongside those of Blaise Cendrars, a Swiss novelist and poet; Ricciotto Canudo, an early Italian film theoretician; and the German Expressionist artist Georg Lewin (aka Herwarth Walden). This tells us something about the company Chagall kept, and the cultural and intellectual melting pot that was bohemian Paris at the time. Together, the names form a square around a heart pierced by a single arrow, symbolising love and suffering. At the time, Apollinaire was a vital proponent of the avant-garde. His poetry, which was often concerned with the clash between the modern and the traditional, juxtaposed drastically different stylistic elements and had a profound influence on artists such as Georges Braque, Marcel Duchamp and Pablo Picasso, as well as Chagall. Connecting Cubism and Orphism with his own structural experiments, Hommage à Apollinaire deploys this dissonant approach to composition.

The incorporation of numbers into the painting is an important signpost to Cubism. Typographical characters had appeared in works by Braque and Picasso since 1911, most notably in the former’s The Portuguese 1911. For Braque, letters and numbers were to be viewed chiefly as objects, to emphasise the materiality of painting, but also to break through the limits of their reality and so create a new reality. While these ideas provided stimulus for Chagall as he experimented with new forms of composition, he was ultimately uncertain about the analytical approach and the objective way in which text was handled by Braque and Picasso. An examination of the preliminary drawings for Hommage à Apollinaire reveals that the numbers started out as three corresponding figures on a clock face: 9, 10 and 11. In Judeo-Christian doctrine, time began with the fall of man and the separation of the sexes. While Hommage à Apollinaire points to this, it may also indicate Chagall’s sense of being situated at a major crossroads in art history where visual art, poetry and philosophy were energetically intersecting, breaking up established conventions of painting.

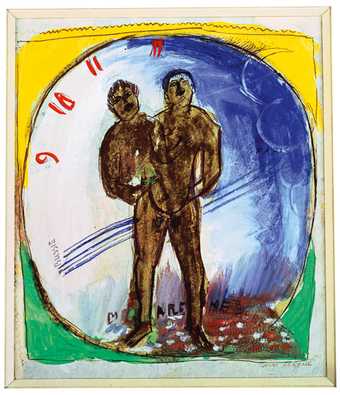

Marc Chagall

Homage à Apollinaire ou Adam et Ève (study) c.1911–2

Gouache, watercolour, gold leaf, pen and ink on paper

24.8 x 20 cm

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2013, courtesy The Bridgeman Art Library, private collection

A gouache entitled Hommage à Apollinaire ou Adam et Ève (study) c.1911–12 provides us with a further clue as to the meaning of the central motif. The two figures, the female recognisable by her breasts, are clearly taken from the Bible story of the creation of Eve from the flank of Adam. In the definitive version of Hommage à Apollinaire almost every trace of the biblical story has been erased. The Adam and Eve characters have an elemental quality that precedes and transcends the particularity of the Christian narrative. At the time, artists in Paris were exploring so-called primitive art in relation to European history and their personal heritages. Chagall drew on his Belorussian folk roots throughout his career, and Hommage à Apollinaire is no exception. The painting indicates two sides of the artist – formally demonstrating his understanding of contemporaneous avant-garde impulses, while symbolically referencing his Hasidic heritage.