Avital Geva was always frustrated by the limitations of being an artist: he was more interested in education, environmentalism and – inevitably, perhaps, given his nationality – the possibilities of coexistence. Yet even when he renounced art to concentrate on running an environmental project, he found his work presented in an artistic context. In 1977 he set up Ecological Greenhouse on the kibbutz Ein Shemer in northern Israel, where he lives. Originally a communal greenhouse, it later grew into an educational experiment in which Palestinian and Israeli kids were invited to participate, and was chosen to represent Israel at the Venice Biennale in 1993. The theme was the art of co-operation. Geva declined invitations to organise similar projects elsewhere, and in 2004 the Greenhouse relaunched itself as a non-profit organisation devoted to education and social involvement.

Detail of Avital Geva's The Books in Landscape Experiment 1972

Fifteen Lambda prints

Each 42 x 54 cm

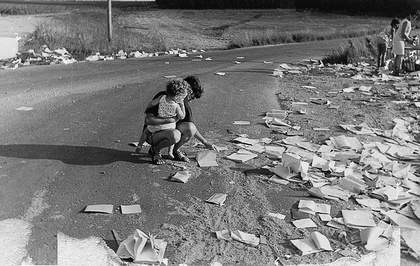

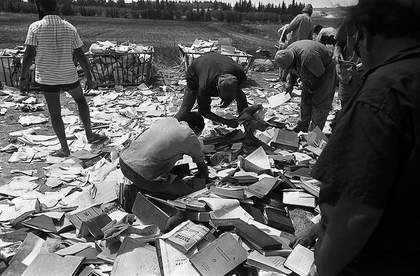

More than 30 years earlier, Geva had conducted a similar experiment in co-operation in Ein Shemer with a project called The Books in Landscape Experiment. He collected thousands of second-hand books, and deposited them in metal baskets on the strip of land that separated the kibbutz from the Palestinian village of Messer. The documentary images evoke different associations. The Nazis burned thousands of books as the reign of terror that would find its most brutal expression in the Holocaust got under way, and Geva’s project seems, in part, a response to their crudeness: instead of destroying books, he was offering them freely to other people. We see a man choosing several and tucking them under his arm, and others flicking through them like browsers in a library without walls or shelves.

Lorries are often witnessed unloading caravans or prefab homes in the West Bank, placed on contested hilltops in another attempt to establish “facts on the ground”. Yet depositing books is the opposite of a land-grab: it is a sharing of knowledge, a renunciation of the rights of possession and a demonstration of the futility of seeking dominance and control. Anyone may take them.

Detail of Avital Geva's The Books in Landscape Experiment 1972

Fifteen Lambda prints

Each 42 x 54 cm

In the early stages of the project, torn pages litter the area. Gradually, the books begin to mulch down into a form of compost, and later they are folded into a wall. Does the process imply an ambivalent attitude to the cultural connotations of the book, or is it an enquiry into the nature of recycling? In the meantime, an impromptu community forms on the roadside: there are Israeli men in shorts and t-shirts, and mothers carrying children. A Palestinian man in a keffiyeh appears in several photographs, seemingly a lone representative from Messer. Was Geva frustrated that more of its inhabitants didn’t get involved? Was that why he renounced the tantalisingly ambiguous gestures of artistic experimentation and progressed to more deliberate attempts to promote the values he espoused?