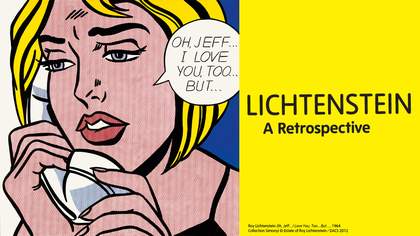

Roy Lichtenstein was just a month short of his 74th birthday when he died in September 1997 of complications due to pneumonia. The creator of perennially youthful works was a family man aged nearly 40 when he produced his first Pop paintings derived from comic books and newspaper advertisements in the early 1960s. Those clean-cut, graphically arresting and slyly humorous early pictures, particularly the images based on romance and war comics and delivered in a crisp style borrowed from their low-culture mass-media sources, are still the works most immediately associated with his name, and for good reason.

The economical pictorial language of flat areas of intense primary colours bordered by assertive black outlines, with flesh tones and shading suggested by a network of coloured dots emulating the Benday dots of their printed sources, remains as alluring today as it was on its first appearance half a century ago. The subtle reshaping of a commercial artist’s pictorial inventions into compositions of classical poise and serenity taunted existing conceptions of high art, undermining both the spiritual pretensions and aspirations to pure abstraction of the Abstract Expressionist generation that preceded him and notions of propriety and the grand tradition still clinging to representational painting then considered outmoded and moribund.

In paintings such as Bread in Bag 1961, Masterpiece 1962 and Tate’s Whaam! 1963, Lichtenstein breathed new life into long-established genres, including portraiture and figure painting, narrative painting, history painting, landscape and still life. This dialogue with the art of the past, invigorated through a sanction of contemporary forms of image-making perceived by others to be at odds with the rarefied sphere of fine art, was to sustain Lichtenstein over the next four decades. The bravado with which he adapted his borrowed language, extended in numerous directions long after the brief comic-book period was over in the mid-1960s, injected total conviction into the picture-making, sculptural invention and printmaking that he pursued unwaveringly as fashions changed around him. The esteem with which he continued to be held was helped, no doubt, by the fact that this most popular of artists – whose art is unapologetically entertaining, humorous and decoratively appealing to a general public – maintained a steadfast conceptual framework for his work and an aesthetic consistency and formal rigour equal to that of the Minimalists who rose to prominence during the same decade.

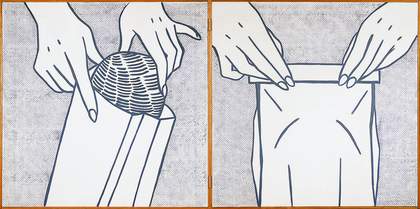

Roy Lichtenstein

Bread in Bag 1961

Oil on canvas

Two panels

72.4x144.8cm

Lichtenstein had a genius for turning things on their head, as in his use in Bread in Bag of the diptych format associated with religious painting to create a narrative of domestic rituals evoking an existential ennui. Drained of colour, like other paintings of 1961 to 1963 limited to an austere palette of newspaper black, this double canvas projects its simplified and wilfully banal imagery with a force that makes it linger insidiously in the mind. When he turned to colour, he at first clung resolutely just to the three primaries and black, knowing that the pictures could then be hung harmoniously in any combination, regardless of their imagery, with the same fierce visual energy running through an entire show. The brightly hued pictures of that period are imbued with the shimmer and effortless appeal of the pop music that filled the airwaves, even insinuating themselves into the true-romance themes of longing and desire that brought drama and emotion to the manufactured songs of girl groups such as The Shirelles, The Crystals, The Chiffons and The Ronettes. Lichtenstein was astute in his identification with pictorial formulas suggestive of ersatz emotion, interleaving exaggerated girlish tears with self-deprecating allusions to his own position as a New York artist basking in new-found acclaim, as in Masterpiece.

Tate’s exhibition, travelling from Chicago and Washington DC and on to Paris, is the first full-scale retrospective since that held at the Guggenheim in New York four years before Lichtenstein’s death. Given the artist’s vast production and the many different directions of what one might term his post-Pop work, notwithstanding the Pop sensibility that runs through all of his art, the curators have sought to lead visitors into a rediscovery of his oeuvre through its many permutations.

There will be a welcome opportunity, for instance, to experience some of the more cerebral series of paintings, including not only the early black-and-white pictures, but also the Entablature series of the early 1970s, inspired by details of the neoclassical façades of New York buildings, and the Mirrors of the same period, in which Lichtenstein comes even closer to the language of geometric abstraction while devising brilliant equivalents for the representation of light bouncing off a silvered glass surface. Juxtaposing flat coloured shapes and dot patterns with areas of exposed white ground on supports whose circular and rectangular formats identify the canvases as concrete and familiar objects, these are paintings of real things and of nothing, or more accurately of the immaterial properties of light. Representational painting since the Renaissance has often alluded to the canvas as a window on to the world, or as a mirror that returns its appearances to us in two dimensions. By showing us nothing but a void, one that lacks not only the artist’s own reflection (as pointedly demonstrated by a 1978 Self-Portrait) but any specific sense of place, the artist leaves no doubt about the mechanics and metaphysics of picture-making as an act of self-proclaimed illusion to which the viewer willingly submits.

Roy Lichtenstein in his studio with Airplane 1978, created for the set of Kenneth Koch's play The Red Robins 1977, published in L'Espresso, 30 May 1982

Lichtenstein took great delight in re-imagining familiar works of art, opening the way to the appropriationist artists of the 1980s, but insisting on his own creative role in reinterpreting and altering his sources in his own voice, much as he had done in his comic-book paintings. There is never a sense of him trying to deceive the viewer, or of passing off a found image as his own; the pleasure, on the contrary, lies in the affectionate translation of sources clearly identifiable to educated viewers into a composition of graphic clarity and economy that rejects the personal handwriting of brushwork, but that paradoxically could not have emerged from any studio but his own. Such is the case with his Artist’s Studio pictures of the mid-1970s. Artist’s Studio ‘The Dance’ 1974 is a homage to Matisse by way of two great paintings permanently displayed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York: The Dance 1909 and The Red Studio 1911. The Lichtenstein version dispenses with the painterly surfaces and colour transitions that characterise Matisse’s work, instead conveying the French master’s imagery and concern with the illusion of space through his own customary restraint and linear devices.

Woman III 1982 goes even further in paraphrasing, almost to the point of insolence, the Woman paintings of the early 1950s by one of the most revered of the Abstract Expressionists, Willem de Kooning. Where the earlier artist had made it a point of honour to create his images through the improvisation of thick impasto on loaded house-painter’s brushes, Lichtenstein reshapes the impulsive brushmarks as flat graphic devices, as he had in his Brushstroke paintings of the mid-1960s, effectively turning a generic de Kooning masterpiece into a cartoon of itself. The procedure anticipates by two decades the methods of the English artist Glenn Brown, whose re-fashioning of Frank Auerbach’s thickly painted pictures as uncanny painted reproductions likewise conflates homage with stinging parody.

It is understandable, given his gleeful embrace of popular culture, that Lichtenstein was once dismissed by affronted critics as an artist capitulating to the contemptibly low standards of the enemies of high culture, the ‘bobby soxers, and worse, delinquents’ alluded to in a March 1962 review by Max Kozloff of a group show featuring his work alongside that of Oldenburg, Rosenquist and others. The final irony in the unfolding of his art is that its sophistication becomes more apparent the more one knows, not just about how all the pieces fit together, but about its self-conscious concern with its own place in a much wider history. The evolution of his work, so much of it a reverie on art history and on the succession of a bewilderingly disparate collection of twentieth-century styles – including the Post-Impressionism of Cézanne, Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism, Purism, Neo-Plasticism, Art Deco, Surrealism, Geometric Abstraction, Abstract Expressionism and Post- Painterly Abstraction – demonstrates resoundingly that Lichtenstein was erudite and wide-ranging in his respectful and good-natured meditations on the work of his predecessors. Nothing, in the end, seemed out of bounds as a point of departure. How else to explain the Perfect/Imperfect series of 1978 to 1989, notionally a rare foray into pure abstraction, but, with characteristic wit, actually faux-abstractions, representational pictures of geometric designs expressed in his signature style?

In his early seventies, Lichtenstein continued to refer in his work to art he respected and found visually stimulating and emotionally appealing. Nudes with Beach Ball 1994 carries echoes of Picasso’s Dinard beach scenes of the late 1920s, as well as of one of Lichtenstein’s own greatest early Pop paintings, Girl with Ball 1961, with more distant allusions to Cézanne’s late Bathers paintings. Always aiming high with his associations, Lichtenstein was supremely conscious of the need to supersede his sources by stamping his authority on his own take of them. Wearing his scholarship very lightly, he succeeds here in conflating the various historical layers, including that of his own youth, into a powerfully emotive picture of sensuous abandon and communion with nature – as always, of course, via a stylised visual language still indebted to his now distant comic-book sources. Through that cool, ‘inauthentic’, shared public language, easily understood by millions, the artist transmits personal experiences common to us all that strike at the heart of memory, physical sensation and emotion.

The Landscapes in a Chinese Style on which Lichtenstein worked during the last three years of his life provide an elegant and poignant end to the exhibition, as to his career. Inspired above all by thirteenth-century hanging scroll ink paintings on paper from the Song dynasty, these twenty or so works, of which several major examples are featured, attest to the extraordinary subtlety that could be achieved with the most basic elements of his lifelong vocabulary. Landscape in Fog 1996 conjures a scene of tranquil beauty using only dots of different size in two hues to suggest a stretch of water, distant mountains and a limpid sky that increases in lightness towards the horizon. The viscous fog of the title is manifested in broadly brushed strokes that have their origins in his pre-Pop, Abstract Expressionist-influenced paintings. In the foreground an angular flowering tree in silhouette insists on the Chinese character of the scene and firmly establishes the artist’s, and by extension the viewer’s, notional position in front of the landscape. Celebrating the beauty of nature by way of the artifice of picture-making, this immersive landscape proves an effective coda to a life lived in the service of art.