I first came across Roy Lichtenstein’s work in a black-and-white reproduction in 1962. Peter Phillips and I had been invited over to the house of Peter Cochrane, director of Tooth Galleries, who had given me a contract after seeing my work at ‘Young Contemporaries’. We were sitting in a large St John’s Wood drawing room looking at remarkable black-and-white photos of what subsequently became known as Pop Art that Cochrane had just bought on a trip to New York. There was work by Jim Dine and Claes Oldenburg, but it was Roy’s piece that stood out. It was Step-on Can with Leg 1961, a diptych painting of a woman’s foot opening a pedal bin. I had never seen anything like it. It was a real culture shock, and liberating. One’s creative imagination was set free.

In 1963 I went to the ICA show The Popular Image, which included a Lichtenstein triptych of a young girl looking out of the canvas with her mother looking over her shoulder. On the left-hand panel there was text that read ‘I tried not to think about Eddie’. I wanted to buy it, even though I had hardly any money. I needed to buy a car for work and it was the same price as a deposit for a VW Beetle… I put the money on the Beetle. Many years later I told Ileana Sonnabend the story and asked her what the picture was worth now – several Rolls Royces was her reply.

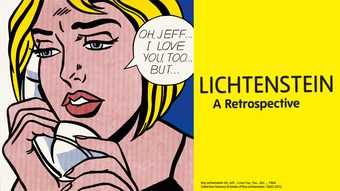

Roy’s use of colour was emblematic. He was not interested in using colours to create depth or kinetic movement in his pictures. In formal terms, I always thought they were as flat as an Ellsworth Kelly. His radical use of commercial imagery was exhilarating. It broke with the whole European figurative tradition represented by the Slade School, where the legacy of Sickert and Bomberg had hit the buffers. Lichtenstein’s work chimed with our own interests at the Royal College of Art in developing a new pictorial language consonant with our times. Cinema, advertising techniques and photography already presented the world in flat graphic terms, in line with our formal pictorial aims. However, the European Pop artists never really got rid of the idea of illusionistic space, and I for one felt closer to the use of colour by the Abstract Expressionists.

I went to New York in 1969 because I had been offered an exhibition and contract by Richard Feigen. I lived at the Chelsea Hotel and soon became friends with Tom Wesselmann and Roy Lichtenstein in particular. On Friday evenings in winter a group of us often went skating in Central Park, followed by supper somewhere. One evening we ate in Roy’s studio where there were too many people to be seated, so he placed one of his large sunset enamels on to trestles so that we could all be accommodated. This gave another meaning to eating as an aesthetic experience.

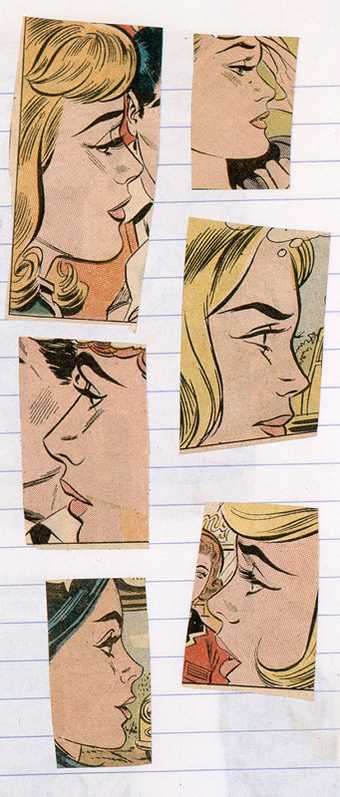

Comic-book cuttings on a page from one of Lichtenstein's notebooks

Roy was compulsively neat. After using the cut-out fragments of comic strips he would carefully file them away, while drawings he made from them, in order to “fine tune” his compositions, were left lying around. He was so taken with the idea I liked them so much that he gave me two, which I promptly pinned on the wall back at the Chelsea Hotel. A few days later he rang to say that Feigen had suddenly shown interest and bought a few of them after seeing them at my place.

Although Roy was a taciturn person, he had a fabulous sense of humour and appreciation of the absurd. Back in London during the 1970s I had his Mad Scientist 1963 on my wall, along with the drawings. It was amazing how many people found them hard to take, even during the 1970s.