Santu Mofokeng began his career as a photojournalist in South Africa in the early 1980s when many of his colleagues were chasing stories on the front line – of civil unrest, attacks on government property and violent clashes with the police – as pressure mounted internally and externally on the white minority government to dismantle apartheid. However, even then he worked according to his own rules and at his own pace.

Mofokeng was a member of Afrapix, a photographers’ collective and agency founded in 1982, which encouraged its members to use photography as activism, and he covered topical issues, but in a different way. Slowed down by his inability to drive a car and, in his words, unable to ‘make the deadlines’, he would print late into the night long after his colleagues had already submitted their pictures and gone home. His photographic style and working methods, which frustrated journalists and editors at the daily newspapers, better suited the Weekly Mail (now the Mail & Guardian), which provided in-depth coverage of the week’s stories rather than breaking news. As he recalls: ‘Being slow became a strength for me.’

As a photojournalist, Mofokeng produced many enduring images of a troubled and complex time in South Africa’s history, but it is his personal work that has distinguished him as one of the country’s greatest photographers. In 1988 he was hired as a photographer by the African Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, a post that enabled him to move away from reportage and pursue some of his own interests.

The photographs he took and exhibited at this time largely sought to document everyday life in South Africa, a subject frequently overlooked as the media focused on the anti-apartheid struggle. It was during an exhibition of these images at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg in 1991 that Mofokeng began to question why he was taking the pictures, and for whom. The experiences of his audience, typically white middle-class people living in wealthier parts of Johannesburg, were far removed from those of his subjects who were living under what amounted to siege conditions.

Santu Mofokeng

The Black Photo Album | Look at Me 1997

A year later he began actively to address this question and proposed an exhibition about Soweto, which would include old family photographs belonging to his subjects alongside his own work, in an attempt to challenge the boundaries between subject and audience and highlight the contrasts between the private and public, personal and political. While researching this project, Mofokeng recalls discovering a number of very old black-and-white family photographs in Soweto homes that he ‘could not relate to’. It was these images which ultimately led him to create The Black Photo Album | Look at Me 1997.

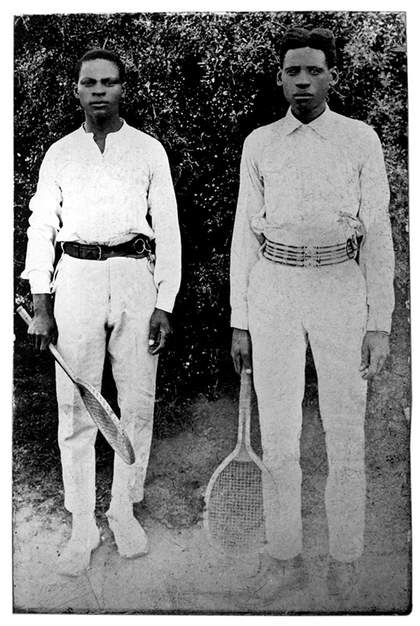

The portraits of black working class and middle class families in European dress that he found displayed on their descendants’ walls or safely stored in boxes and albums were taken in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They are remarkable because they appear to have been either commissioned or sanctioned by the sitters, whereas most photographs taken of black people in South Africa during that period were of coerced subjects which served as mementos for the traders, missionaries and colonialists wanting a record of their time in the colony.

Painterly in style, these photographs evoke the artifices of Victorian-era photography. For the most part they were taken in highly controlled settings, typically the photographer’s studio, against a neutral or painted backdrop. The dress and props would have been carefully chosen to capture or embody the subject’s personality, or redefine them in a new role, and it is likely not all the items belonged to them. Mofokeng explains: ‘If you look closely at the clothes, you notice that the face or faces of the subject were put there, airbrushed in afterwards.’ He continues: ‘One could find similarly clothed subjects with different faces in another house: the clothes are the same, only the faces are different. It’s the work of an enterprising photographer and artist. There is a lot of fiction.’

The Black Photo Album | Look at Me consists of 80 slides, approximately half of which are digitally reworked scans of photographs Mofokeng collected from nine different families across South Africa. The images are interspersed with slides containing information about the sitters and photographers, which he gathered from the prints themselves and from interviews conducted with the subjects’ relatives. These texts indicate that at least some of the people depicted were integrationists who received Christian mission school educations, owned property and considered themselves equal to European immigrants, since their lives and aspirations were similar. However, several captions also reveal that the roots of apartheid existed long before the National Party assumed power in 1948, none more forcibly than the opening quote from J.B.M. Hertzog, Prime Minister of South Africa from 1924 to 1939 and one of the principal architects of the Representation of Natives Act, 1936, which removed black people from the common voters’ roll: ‘With the so- called civilised workers, almost without exception, their civilisation was only skin deep.’ Throughout the work, Mofokeng inserts his own voice, questioning who the subjects are, where, when, why and by whom the images were taken. He also asks repeatedly: ‘Are these images evidence of mental colonisation or did they serve to challenge prevailing images of “The African” in the Western world?’

Mofokeng has created an archive of inestimable value, brought to light in the post-apartheid era, that reinvigorates narratives about identity, lineage and personality and reveals the richness of black family life in South Africa at the turn of the century.