Caterina Albano on Leonor Fini’s Little Hermit Sphinx 1948

Leonor Fini

Little Hermit Sphinx (1948)

Tate

I immediately think of Piero della Francesca’s Brera Altarpiece 1472–4 when I see Fini’s painting. The suspended organ instead of the hanging egg must trigger the mental association. Perhaps the broken eggshells prompt the comparison. Then I read that Fini loved the Brera Altarpiece. Maybe the mystery, the uncertainty, is that they are both about a threshold. And as the two images start to melt in my mind’s eye, I find myself drawn into Fini’s painting, completely absorbed into it. I stand there at the threshold with the little sphinx crouching at my feet. Her diaphanous childlike face does not turn towards me. Her gaze is fixed on the edge that demarcates the entrance. We are both motionless. Suspended in stillness. Moulded walls separate but do not divide this space where inside and outside do not exist. Debris is scattered around, a faint smell of rotten flesh fills the air. Slowly I also crouch down, sitting cross-legged on the ridge of the doorstep, and fix my gaze on the edge of this doorsill, hazy in front of my downcast eyes. I can hear the shallow breath of the sphinx next to me, and wonder if she can perceive the pounding sound of mine. Still we do not look at each other. Pain keeps us apart. Pain keeps us here. Nor do we look around with expectation or, for that matter, with a feeling of loss. We are simply incapable of moving away from this bare threshold, of yielding away from fear.

Hong Ling on J.M.W. Turner’s Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth c.1842

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (exhibited 1842)

Tate

The concept of landscape painting in the East and West is rather different in my view. Western landscape paintings often put a lot of emphasis on rationality and being truthful to the scenery. Whereas the Chinese equivalent, known as Shan Shui (literally ‘mountain- water’), depict the landscape in ink and brush, giving greater significance to the Chinese philosophy of humanity and heaven (nature) being united as one. My aim is to convey the Chinese aesthetics of the universe – ‘my mind is the universe; the universe is my mind’ – through oil painting, a medium with its roots in the West.

J.M.W. Turner, for me, sits above the traditional Western landscape painter. He brought emotions and humanity into his romantic portraits of nature, as in one of my favourite works, Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth, which was fortunately shown at his first major exhibition at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing last year. Turner was ahead of his time. He created his own style by breaking through the rigidity of landscape painting, and, for this alone, he earned my great respect and admiration.

Rosa Barba on J.M.W. Turner’s Reflection in a Single Polished Metal Globe and in a Pair of Polished Metal Globes c.1810

Joseph Mallord William Turner

Lecture Diagram: Reflections in a Single Polished Metal Globe and in a Pair of Polished Metal Globes (c.1810)

Tate

London 1810, a rainy Tuesday morning, and I walk briskly through the centre of the city. As usual, I am distracted by startling objects, situations and incidents that surround me. Suddenly, I find myself hemmed in by many others joining the same route. I remember my task and rush onwards.

The buildings move behind me, new gaps open up. As I walk onwards, the framing of the streets and buildings ahead of me changes; they teem with echoes.

Finally, I arrive at my destination: Room 202 of the Royal Academy of Arts. I step beyond the squeaking door, and am surprised to find myself standing close to J.M.W. Turner and his father William, who has already begun his lecture on perspective.

The class is silent, and I am so close to the drawing that I can see my mirror self, reflected in one of the two polished metal globes that old William is holding aloft, facing his audience. I continue to look discretely, cautiously but intently into the globe – I absorb the content of its wordless communication.

Inside the globe, the dimensions of the classroom bend in every direction. I am not invited to sit, but am allowed to remain in this same place for the rest of the lecture.

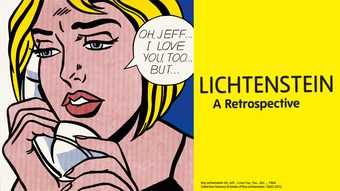

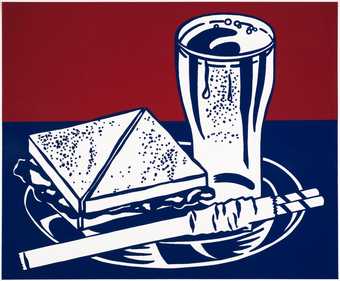

Henry Holland on Roy Lichtenstein’s Sandwich and Soda 1964

Roy Lichtenstein

Sandwich and Soda (1964)

Tate

I have always loved Lichtenstein’s work, and when I first moved to London I bought a print of Ohhh…Alright 1964. My friend bought one too. We both still have it on the wall in our houses, so it – and the artist – has really personal meaning for me. I like the girl’s sarcastic tone, and the comic-book layout.

Lichtenstein’s instantly recognisable motifs and imagery now lend themselves to fashion and film, just as he borrowed from comic strips and advertising to create fine art. This particular piece, Sandwich and Soda, is no exception and is the perfect iconic American image. His paintings managed to be simultaneously satirical and celebratory, using references from familiar objects and the media around him to comment cleverly on an interesting period in US cultural history. For me, this totally represents that period; a very accurate documentation of something quite banal, yet still quite humorous.

His work continues to be a source of inspiration to so many designers working today. For example, Whaam! from the Tate collection is currently being used on New York-based designer Phillip Lim’s knitwear and accessories. Lichtenstein’s use of colour is brave, and this, coupled with the bold lithographic style, speaks to people who are involved in creating objects that make a visual statement. In his more abstract pieces, I love the feeling of movement, as if the brush has literally just left the picture with the paint still wet and dripping down the canvas, but Sandwich and Soda is so unapologetically static – yet still full of energy and vibrance.