A plate of redcurrants on an old, prosaically weather-beaten table. The plate – blue and white, with formal Chinese motifs – would seem to be willow pattern, and the light in the image appears to come from the objects themselves, especially from the berries, all of which suggests one of those old still-life paintings we take so readily for granted, something by Adriaen Coorte, say, or Chardin’s Wicker Basket with Wild Strawberries of 1761. Yet this is a contemporary image, a photograph by Peter Fraser, one of a series of pictures in which a washing line in a snowy backyard, or two empty buckets – one pale blue, the other somewhat darker – set side by side on the floor of what might be a school or a community centre, are transformed into reminders that, as we go about our day-to-day business, we miss almost all there is of actual, physical reality in our lives.

The missing is, of course, deliberate, or at least predetermined: we have better things to do than to stop and take stock of where and what we are. Yet while it may seem frivolous to say so in the current climate (though, of course, there is always a ‘current climate’ of one kind or another), the fact remains that our foremost, and mostly neglected first imperative is to make the key distinction between the mundane (the governed, the preordained, the authorised) and the quotidian (the wild, the immediate, the erotic), for this is the first step in refusing to be governed, the first step in imagining a world that nobody owns.

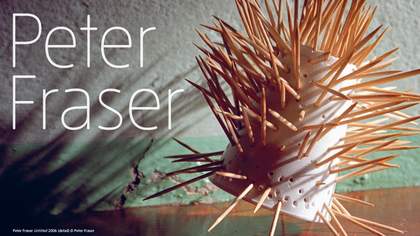

Peter Fraser

Untitled from A City in the Mind 2008–11

Archival pigment print, 65 x 88.9 cm

So, while it would be easy to pretend that Fraser’s work is apolitical, I would suggest that nothing could be further from the truth: for, as with Dutch still life or the domestic scenes of Chardin’s most intimate work, a strange, yet essential democratising force can be discerned in his oeuvre. As we peer into his illumined, sometimes child’s-eye-view pictures of scale models and berries and abandoned toys, we are reminded that we are all of us equals in the chambers of our imagery, and that it is only the mundane world that assigns us positions and pay grades. In the immediacy of the quotidian, no one’s experience is more or less vivid than another’s, even if it remains unsayable.

Il y a un autre monde, mais il est dans celui-ci, says Paul Éluard, which is to say that, behind the veil of the mundane, the quotidian endures, whether it be in the roseate, deeply erotic curve of a seashell, the forlorn quality of an old grocer’s scale in the corner of what might or might not be an empty room, or a stack of breeze blocks that somehow suggest, in their translucent violet wrapping, a long-lost pharaonic mystery that, even if it no longer exists in the mythical ‘real world’, remains encoded in the viewer’s prehistoric self.

Fraser’s work constantly undermines our assumptions about that Realworld (constructed playground of received ideas and invested power, sanctuary of the hidebound, the limbo state of a long ossified yet oddly stubborn Authorised Version, pressed upon us from birth by those charged with rationalising our behaviour – parents, teachers, policemen, our supposed peers), and no matter how poignant the gap between the quotidian and the mundane may be, we are reminded that it is possible to cross over at any time into an autremonde that is neither misty nor ill-defined. On the contrary, it is the murky shambles of the Realworld that blinds us to the basic data of experience – form, colour, light, depth of field and, least available to denotation but most important of all, the vibrant and surprising presence of the thing in itself that we call is-ness or quidditas, a here and now presence steeped in Urlicht, mysterious, vivid and, at the same time, undeniably quotidian.

Peter Fraser

Southampton from the series 12 Day Journey 1984

C-type print, 50.8 x 60.9 cm

In many ways, it is impossible to write about Fraser’s work, partly because its very purpose is to render us speechless and partly because its vivid actuality is the very antithesis of societal, paraphraseable experience. To be present with these images is to sidestep the tawdriness of Realworld existence and slip fortuitously into the same light that informs our dreams, a clear, pagan light that is the absolute opposite of what Heidegger calls ‘the light of the public that darkens everything’. Yet what can be said here, or rather uttered, is a word or two of recognition that takes us, not back, but home again to the Ur-light of the Dutch still life painters, to the autremonde of Chardin, or even to the pregnant pause in the annunciation paintings of Alesso Baldovinetti or Simone Martini, where clock time is suspended and every ‘object’ in the room is suddenly lit from within and, so, made divinely manifest.

Is this political art, then? I want to be perverse and say that it is, for the reasons given: it returns us to the wild, to the vivid, to the erotic qualities of everyday life, and so separates us, for a time, from the realm of the mundane, where everything is governed. That the separation is temporary is neither here nor there: what matters is that it is exemplary. For a moment, we have remembered how to look – that is, how to be attentive to the quotidian – and that could make all the difference.

Peter Fraser

Easton, nr Wells from the series Everyday Icons 1985–6

C-type print, 50.8 x6 0.9 cm

A plate of biscuits. A basket of crayons. A brick fireplace. The real world is physical and immediate and nothing is ordinary, or trivial, other than the mindset that does not know how to see what is really there. We come into the world and we grow up being told what matters, and to what we must offer up our regard; every time that conventionalised way of seeing is contradicted is a liberation of sorts, a first step on the path to discovering what is actual, within ourselves and without, as opposed to what we were instructed to find. Once taken, that first step sets us on the road to a place where everything is different – time, space, presence, light, all physical bodies. Suddenly, everything is erotic. Suddenly, the mere noticing of some formerly overlooked presence is a revolutionary piece of cartography, in which the world is remapped for dwelling, as opposed to the mere existence of the preordained. Suddenly, things are as they always were. Real.